您的购物车目前是空的!

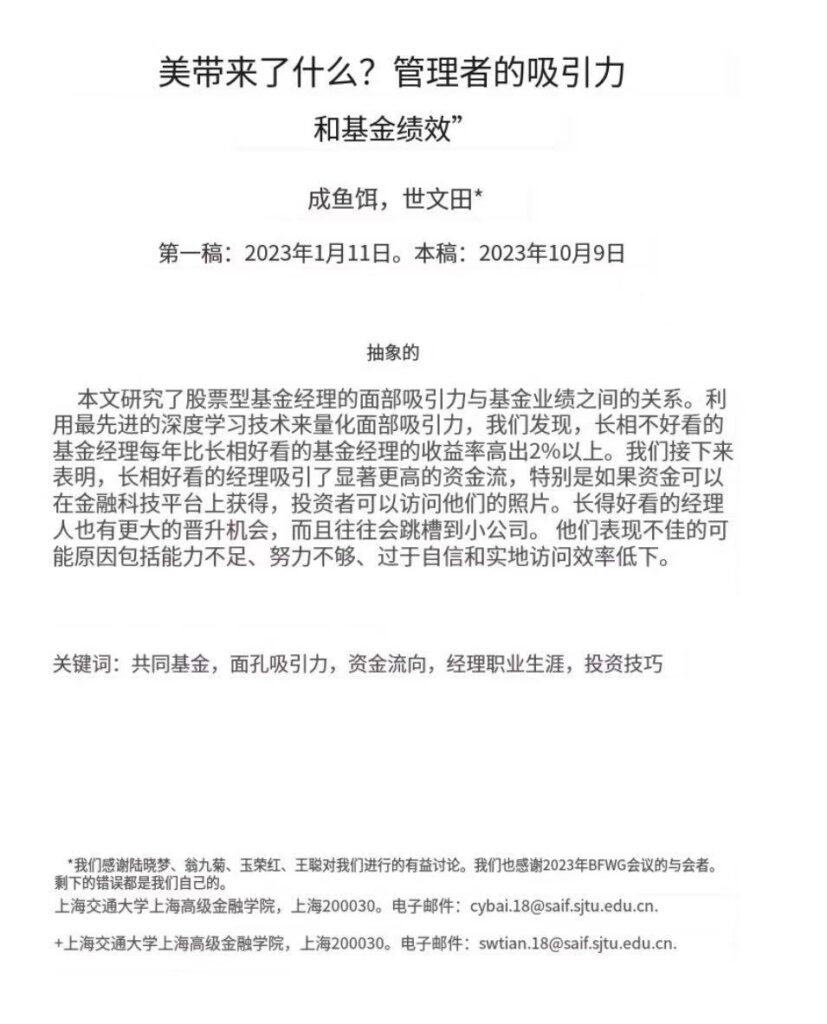

作者: deepoo

骗局经典

陈世鸿:金融茶

2023年12月3日,在芳村,有数十名购茶者、茶商聚集在一家名为“昌世茶”的门店外,高喊“退钱”。

有茶商介绍,昌世茶先推出四款茶叶产品,以“没有书面约定”的回收价格吸引茶商参与,两个多月的时间把产品的单价从每提(茶叶交易单位,每片重357克,每提7片)3万元左右炒到最高7万余元。之后,昌世茶以高价推出第五款产品,吸收一拨资金后,“接盘”动作戛然而止。茶商透露,上述产品在一夜之间“崩盘”,从单价5万多元跌到只剩下两三千元,参与其中的茶商损失惨重。

据报道,数百家茶叶商户持有的几十万元乃至上百万元的茶叶,一天之内价格“崩塌”,从单价5万多元跌到只剩下两三千元,参与其中的茶商损失惨重。据市场里的茶商初步统计,涉及此次纠纷的茶户数量达五百人以上,涉事金额超过5亿元。这成为芳村茶叶市场里爆发的最大的一起纠纷事件。

有茶商表示,他们打款账户的户名有李业聪、陈棒磊和陈文帆,前面两个人曾为昌世茶的股东,陈文帆为现任股东。

多位茶商表示,由于缺乏“承诺回收约定”等证据指证昌世茶,警方尚未立案。2023年6月,一家名为广州市昌世茶茶业有限公司的茶叶厂商完成注册,此后进驻芳村茶叶市场,9月正式卖茶,开幕式上500人汇集,横幅林立,醒狮舞动,相当隆重。同时推出产品“昌世茗雅”售价41888元/提,看上去可谓高级。开幕仪式上,昌世茶已建立起庞大的茶叶交易群,当晚就有茶商在里面卖货。

“41888出1-10提昌世茗雅,现货私聊”,几分钟后又有人“42888出1-10提昌世茗雅”,同时有人回复“拍1”“拍2”,确定下单数量。如此反复等提高到一定价格后才会停止。

据称,这些交易的人有一些是茶商,是昌世茶的“托”。它们晚上八点半会在群里叫卖,持续时间不超过半个小时,价格一般能高出售价几百元,期间会带节奏、喊口号,似乎参与了就能赚到。

同时,他们擅长“饥饿营销”,昌世茶的前四批产品都是限购的,散户只能认购2-3提;有茶商想加入加盟商也被拒绝了。

出完货,这些“托”还不时在群里高价回购,让参与的茶商获利,一个月下来可赚4、5千元。

昌世茶如此火爆,自然成了芳村茶商们谈论的话题之一。平日里,茶商们打开门做生意,经常有人进店看茶、品茶。大茶桌上,三五朋友围坐喝茶闲聊,讲到昌世茶都会互相问句“你买了没,要不要一起买”,甚至调侃道“一夜赚一万,这都不入,你实力还是差点意思呀”。

据称,“托”们还会在群里发上百元一个的红包,出手阔绰,中秋节给茶商送月饼。这在外界看来,公司实力相当不错。

另据一位芳村的茶商向易简财经透露,这些“托”,有些甚至是在市场建立起口碑的平台,一定程度上也给昌世茶提供了信任支撑,看着很有保障。但背后他们可能也跟品牌合作了,微信群里可能500人,400个都是托。

两个月后,玩家越来越多,昌世茶的价格也水涨船高,每提由原来的3、4万最高涨至7万元。

打破常规,一夜之间庄家不玩了

昌世茶的炒作进入看似平稳运营的状态后,其又准备了第五款茶“昌世雄峰”。

11月28日,“昌世雄峰”发布,售价比以往都高,达到52000元,且不再限购。一些观望已久的茶商也决定上车,据说参与人数是前所未有的。

但吊诡的是,据称11月30日微信群里的“托”在晚上8点并没有出来叫价,直到十点才现身,且口吻统一“44000找雄峰,有多少要多少,客户上车抄一下底”。

这次回购竟低于售价,茶商不明就里不敢轻举妄动,而部分敏锐的茶商则忍痛卖了。之后,“托”不再现身,群里出货的价格也越来越低。直至接盘的人仅开价2000元,大家仿佛才被一盆冷水浇醒。

有茶商指出,所谓金融茶,即制造稀缺和高收藏的假象,承诺高价回收引导茶商入局,让茶叶看起来有升值空间。

金融茶一般限量出货,方便控盘的同时,茶商也容易拿到定价权,不往市场放货就方便提价,就算喊出100万/提,只要能成交就是新的定价。

如果有人买来送礼或饮用,100万/提的价格就兑现了消费价值;如果没有人买,就会让茶商带资进来捂盘,抬价继续卖。此举还会促使厂家让托高价回收和卖出,形成完整的交易流程。

但是,这个过程操盘要稳,需要茶商持仓一到两年,给“托”抬价的时间。不断滚动后让更多人参与,才能让前期投资早的茶商赚到钱。

而昌世茶3个月就收网,打破了以往的规则。有位参与者就表示:“我知道这是一个赌局,但没想到一夜之间庄家不玩了。”

昌世茶暴雷后,有部分茶商前往门店维权,有的到公安局报案,但都没有好结果。在警方看来,这是市场自发行为,茶商们也没有昌世茶承诺回购的证据。

昌世茶的董事长陈世鸿曾回应:“事件自始至终不存在违法行为,纯属生意,公司没有任何人承诺任何回购价格,所有买卖都一手交钱,一手交货。”

据报道,昌世茶的回购是通过托来实现的,托跟散户之间或有口头承诺,但没有白纸黑字的约定。至于加盟商的话,签约内容也是简单地注明了加入时间、押金和配货金额,没有包括回购在内的承诺。

对此,有律师表示,如果此次承诺回购是事实的话,没有书面证据,也可以提供相关的微信qq等聊天记录、电子邮件等,哪怕是证人也是可以的。

00后掌门人惹关注,身份神秘

昌世茶暴雷后,一时之间在网上引起关注。其董事长陈世鸿也被推到聚光灯下。

据公开资料,陈世鸿是一个00后潮汕小伙,曾在类似的“金融茶”平台工作过。开幕式上,他身着POLO衫现身,体格瘦削。

据一位芳村茶商透露,陈世鸿在业内并不出名,而他作为00后估计也是没有操盘炒茶的能力的,猜测是因其潮汕人的身份被推到了台前。

带有风险的炒茶行为,通过同一地域的人际关系能更快地拓展网络,也更易让人相信自己不会从中吃亏。据上述茶商透露,此次被套的90%是潮汕人。

而公司的股东,据企查查显示一位是陈文帆、一位是刘嘉豪,但两人均未任职其他企业。

据报道,涉及此次纠纷的茶户数量达五百人以上,涉事金额超过5亿元。这成为芳村茶叶市场里爆发的最大的一起纠纷事件。

对此,有金融人士认为,从这个数据看来,估计是雪球还没滚大就崩了。如果把昌益茶的炒作放到股市来看,其实就相当于庄家自己人把价格炒高,本来要拉出8个涨停再出货,正常情况下是要扩散到更多散户接盘的,但昌世茶似乎才拉到2个涨停就崩掉了。

其还表示,这个可能是因为他们自己资金实力不足,加上年底市场资金紧张,部分人还要回笼资金,一下子就资金链断了。如果要是让他们做大,说不定是百亿级别。

其还指,市场上炒作最强的,其实是大益茶。其大益班章六星孔雀青饼,一度在2021年炒到6500万元/件,可谓“天价”。假设有100个人买入,涉及的金额就能达到65亿元。

2020年,炒作大益茶在东莞就制造过大雷。东莞近百茶商和藏家买入一年后无法兑现,据不完全统计涉及本金超过1亿多元。

现在,市场上暴雷的还有茶有益,陷入争议的有泛茶。在茶商看来,茶叶因为没有标准,难以检测,所以常常被当做炒作对象,认为这种“金融茶”依旧会反复出现。

芳村的名气,在全国茶圈人尽皆知。它不仅是全国最大的茶叶批发交易市场,更是全国普洱茶的交易重镇。公开资料显示,每年全国普洱茶交易量的八成,都在这个超22万平方米的市场里完成。有茶商认为,炒茶行为已经对芳村的形象带来了影响。

相似的模式在市场上反复上演,比如藏獒、金钱龟、蚁力神等。

李业聪曾现身昌世茶的开业典礼。当时的宣传物料显示,其来自广东万基拓展实业集团,该公司在电话里称,李业聪只是该公司一名员工,不是高级管理人员。

昌世茶崩盘之后,有部分茶商到公安局报案,希望可以立案处理。但是警方认为,这是茶商自发的市场行为,即“自己买茶买亏了,掉价了,现在不服气,找厂家理论”。有茶商认为,更为重要的是,他们没有实际的证据证明这是一起涉嫌非法集资的诈骗事件。无论是加盟商签订的合同,还是微信群里的聊天记录,没有任何承诺回收的字眼。茶商“托”口头上说有承诺,但是茶商在面对面询价交易的时候也没有录音,没办法指证。

广州市昌世茶茶业有限公司成立不足一年,陈文帆与刘嘉豪分别持股60%于40%。昌世茶董事长陈世鸿是一位“00后”潮汕人,曾在类似的“金融茶”平台工作过。据九派财经报道,12月4日下午1点左右,昌世茶公司董事长陈世鸿由警方带离门店。

昌世茶第二大股东刘嘉豪称:昌世茶从来没有对外承诺过回购茶叶,没有强买强卖,也从来没有承诺会上涨多少。

12月8日,陈世鸿表示,没有承诺回收产品,昌世茶的经营都是自己一个人做的,没有其他人。李业聪是自己的朋友,自己的账户不方便使用,所以用了李的账户;陈文帆是自己的亲戚。对于茶商“托”,陈世鸿称,那都是茶商的说法,其实没有托,昌世茶是现货的模式。

目前,昌世茶的理赔方案暂时只对接自己的加盟商,至于加盟商与其他茶商间的纠纷处理,后续会有方案公布。将茶叶做成理财产品,凭借一张“提货单”而非茶叶本身流转盈利,在业内被称之为“金融茶”,一直备受争议与关注。这不是芳村茶叶市场第一次出现“金融茶”崩盘。而对于过去的事件,警方多予以立案,涉案金额一般没有超过1亿元。

今年7月,有广州市民向记者反映,他们花重金参与了一家茶叶公司推出的普洱茶回购活动,到期后对方却没有按承诺买回茶叶,甚至卖茶公司都已停止经营。

杨女士今年4月开始接触到广东茶有益茶业有限公司(简称茶有益公司),对方的业务员向她推荐了一些“具有理财价值的”茶叶产品,并且承诺30天之后将由公司回购,届时茶叶价格若有上涨,就作为她投资理财的收益。“他把我拉到一些微信群里,每天都有业务员在里面发茶叶的回收价格,每天的回购价都在涨,搞得行情看起来非常火热。”

面对高额的回购承诺,杨女士先花3万多元购买了一提(普洱茶常用的包装形态,一提通常有7饼茶叶)某品牌普洱茶“试试水”,30天后公司果然将其回购。在茶有益公司,这款茶叶的回购报价几乎每天都在增长,一进一出之间,杨女士获得了大约2800元的投资利润。有了这次投资经验,她在随后的一段时间里陆续投入大笔资金,共买下16提普洱茶,花费60余万元。

但这一次,投资者们没有等来茶有益公司的如期回购。6月14日,杨女士和一些投资者在茶有益公司组建的交易群中询问回购安排,却被业务员告知“公司没钱了,不会再回购茶叶”。紧接着,这些每天都在热烈讨论回购茶叶的微信群,也被茶有益公司负责人悄然解散。

“之前都跟我们承诺回购茶叶,现在又说不要了。”回购热潮停止后,杨女士意识到自己可能被套路了,“大家回过头发现,群里业务员发的消息是最多的,每天都在哄抬茶叶的回购价格,吸引我们去买来持有,等着他们回购。”有投资者表示,没了茶有益公司的回购,他们手上的茶叶根本值不了三四万元一提的价格。因此,他们认为这是茶有益公司谋划的敛财跑路戏码。据投资者们自发统计,目前被茶有益停止回购茶叶的投资者有200多位,累计投入金额约5000万元。

此前每天都有业务员刷屏的茶叶交易群,已被茶有益负责人解散。

茶叶涨幅全由老板决定 买卖交易全凭一个“信”字

涉事的这款名为“拾伍”的普洱茶,在网络上并没有公开售价,在茶有益公司开发的小程序上,这款茶叶的出厂价格显示为4800元一提。该茶叶在茶有益小程序上的行情价格以每天每提100-200元的涨幅不断上涨,截至6月14日,最高行情价格为42400元一提。

茶有益公司停止营业后,有业务员告诉南都记者,他从今年2月初开始在茶有益做回购“拾伍”等茶叶的业务,这些茶叶的所谓价格涨幅并没有参考依据,涨多涨少全由公司老板当天通知,再由业务员更新到微信群和小程序中。

值得注意的是,投资者多数是在茶有益业务员的引导下,从包括茶有益在内的四家指定茶商处购买“拾伍”普洱茶,再由茶有益统一回购。回购要求也相当严格,“如果包装被拆,或者不是完整的一提茶叶,公司都会直接拒收。”因此,不少投资者只将其作为一款金融理财项目,投资购茶后也未真正持有茶叶产品,与茶有益公司的所有交易以及约定,都是通过微信对话完成。

多位受访投资者告诉记者,作为常年在茶叶市场做生意的商家,不少人都没有签合同的习惯,买卖交易全凭一个“信”字。茶有益公司的业务员在推销和回购茶叶的同时,自己也在跟公司购买茶叶,等待被回购赚取利润,有的甚至刷信用卡或借钱去囤积茶叶,“才跟公司做几个月,从来没想到会爆雷”。

工商登记信息显示,广东茶有益茶业有限公司成立于2020年9月,原法人代表为肖某,2023年4月变更为林某。不少投资者称,之所以会相信茶有益的回购计划,是因为肖某和林某从业多年,具有一定的影响力,大家愿意相信他们。

6月底,南都记者走访茶有益公司办公地址,现场大门紧闭,透过玻璃窗可看到室内装潢还留有“茶有益”等字样,但门口的招牌已被拆除,旁边墙上还挂有属地街道与派出所、市场监管部门联合制作的“天上不会掉馅饼,谨慎对待投资理财”横幅。现场有投资者称,目前负责人已被警方控制,相关情况正在调查中。

茶有益公司办公地点,招牌已被拆除。

据茶有益官方微信公众号7月6日发布的消息显示,该公司负责人确已在事件爆发后,被采取刑事强制措施。该公司为此提出一项和解方案:每提“拾伍茶叶”对应补偿现金人民币2万元加一提同款茶叶,同时拥有者持有的“拾伍茶叶”亦无须退还。至于投资者的回购诉求,茶有益公司未再提及。杨女士等大多数投资者并未接受该方案,“四万多元买的茶,现在变成两万,剩下的损失都要我们自己承担,大家没法接受。”

政府部门号召广大商户 警惕非法集资,防范违法“炒茶”

茶有益等公司的“炒茶”行为引起政府部门重视。8月30日,广州市荔湾区发展和改革局向荔湾区茶业产业商户发布《告知书》,号召广大商户警惕非法集资,防范违法“炒茶”,诚信为本,守法经营,担当社会责任。

《告知书》称,近期发现茶叶市场有涉嫌违法的“炒茶”行为,严重扰乱茶叶市场秩序,影响荔湾区茶产业健康可持续发展。“金融茶”“天价茶”等炒茶行为存在风险,交易中或构成非法吸收公众存款与集资诈骗罪,要求广大商户要坚决抵制以上违法行为,警惕非法集资风险。

9月11日,南都记者从一名投资者处了解到,目前已有部分“拾伍茶叶”投资者选择接受补偿。该投资者还透露,目前属地公安部门等均已介入调查,投资者们都在等待官方的进一步处理。

9月14日上午,广州市荔湾区发展和改革局回应南都称,针对茶叶市场“炒茶”线索,区委区政府高度重视,区发改局组织相关部门对茶有益等涉事企业进行走访约谈,对相关线索进行甄别,目前区公安部门已介入调查。此外,荔湾区发改局还联合广州金融风险监测防控中心、律师事务所等第三方服务机构,对涉事主体包括经营方式、经营范围、合同兑付情况等方面进行线索甄别、风险监测。并会同相关单位开展多轮跟踪研判,协调属地街道、派出所等做好风险监测、事件调查研判定性等工作,及时掌握最新情况;密切与区商务、区市场监管等行业主管部门沟通,告诫各商户要自觉遵守商圈自律规则,确保市场秩序健康。

街道和派出所在茶有益公司外挂起提醒标语。

“金融茶”基于“滴水滚珠局” 是一种新型的“庞氏骗局”

12月6日,“广州荔湾发布”发文称,在传统经营利润日益微薄的情况下,茶商通过炒作的方式抬高茶叶价格,高价的“金融茶”往往是资金堆砌和控制发行量的结果,通过锁仓和对敲等手段,不法茶商便能够轻松将茶叶商品转变为金融产品从而获利。新进茶商是“金融茶”市场的主要潜在参与者。与2007年和2014年的炒茶高峰不同,2021年炒茶高峰出现了量在价先的迹象。茶商数量的急剧下降导致增量资金无法持续,进而导致近期来“金融茶”“理财茶”的“爆雷”事件层出不穷。

“广州荔湾发布”发布的文章提到,部分新设茶叶厂商模仿大厂商发展路径,通过集中宣传造势、招揽加盟商,“另起炉灶”打造新“高端”品牌。为了快速变现,新品牌通过对加盟商的兜底回购条款刺激押款压货数量。原本随行就市的茶叶波动,变成了一种“固定+浮动收益”的理财产品,而新品牌茶叶就是理财产品的“底层资产”。茶叶市场上这种以“注水资产”为基础,通过承诺收益的行为存在高度的诈骗和非法集资风险。

当下盛行于茶市的“金融茶”骗局基本属于传统上所说的“滴水滚珠局”,是一种新型的“庞氏骗局”。

“滴水滚珠局”的逻辑是寻找稀缺性资源,或不容易批量生产类型的产品,经过加工赋予其新的特性,然后鼓吹市场前景以及其稀缺性,拉升产品价值,通过造势、捂盘限量投入市场,拉长战线,拉升价值感,分阶段进行品相叠加,最后高位抛盘,提现走人,制造或寻找下一个风口锚点。

所有“金融茶”骗局都是以高回报为诱饵,承诺的回报率甚至超过20%,但这种承诺都不会写进合同,只是通过聊天等方式进行宣传。由于茶叶交易多以口头商定、微信交付的形式为主,对茶商的信任也源自多年积累的口碑和声誉,一些出面做局的人大都有各种各样的头衔加持。他们像炒股一样,通过“枪手”拉高打低反复收割,甚至茶叶根本没动,只是对单交易。这种以理财为名义的炒茶方式,即使有合同等外衣,实际也可能构成诈骗。

广州市荔湾区发改局(荔湾区处非办)、区公安分局、区市场监管局及广州金融风险监测防控中心提醒,公众品鉴、收藏茶叶时,应聚焦茶文化和茶本身的价值,拒绝“金融茶”投机活动,防范非法集资风险;切记任何投资都存在风险,要警惕打着“保本”“高收益”旗号的任何形式的理财产品。一旦发现涉嫌市场诈骗、非法集资的行为,广大群众应该及时收集和保留广告宣传资料、录音录像、合同协议、转账凭证等涉嫌非法集资的线索,积极向荔湾区发改局(荔湾区处非办)举报或向公安机关报案,举报一经核实将依法依规予以奖励。

国内“金融茶”屡爆雷多地监管部门关注近年来,屡有媒体报道天价茶叶价格暴跌事件,背后都指向“金融茶”的炒作与崩盘。

据报道,2021年下半年,以大益茶等普洱茶品牌为主的“金融茶”产品出现崩盘形势,引发普洱茶行业乃至整个茶叶行业震动,不少茶行和炒家资金断裂,一夜蒸发千万资产。调查发现,一款大益2003年批次的“四星班章大白菜散筒”,在2021年3月底行情价为160万元一提,至6月27日价格直接腰斩,仅剩80万一提。彼时有茶叶业内人士认为,“金融茶”产品缺少监管,后台交易数据可以随意操控,为交易市场的爆雷埋下不少隐患。对此有茶商呼吁,“远离炒作茶叶,回归普通消费,注重产品本身品质,让茶叶行业重新回到正道上。”

同样在2021年下半年,广东、云南等多地监管部门与茶叶行业协会均发布文件,提示金融茶产品风险,指出“金融茶炒买方式和价格泡沫次生风险极大”。今年6月30日,云南省西双版纳州召开“整治普洱茶‘金融茶’乱象”专题座谈会,痛斥“金融茶”乱象危害大、影响深,损害消费者利益,破坏市场流通秩序,不利于茶产业的健康持续发展,参会的茶产业链从业者也纷纷表示,全力配合“金融茶”乱象整治行动。

走访茶有益公司期间,有茶商认为茶有益公司打造的并非金融茶产品。“我也接触过‘金融茶’,把茶叶按照期货交易的方式进行炒作,盈亏全看市场变化,赔了也心甘情愿。但茶有益的回购是带欺骗性质的,我们认为它就是非法集资,是诈骗行为。”

也不是没有投资者对茶有益的回购模式提出过质疑,但种种怀疑都被公司法人的背书以及高额的回报所冲淡,有投资者还引用了《狂飙》的台词来诠释自己的想法,“(当初)也知道投它有风险,但都说风浪越大,鱼越贵。”

6月19日,广东省茶业商会等联合发布倡议书,倡议各会员单位依法依规守法经营,抵制期货交易,不参与非法集资理财经营活动,交易过程中以合同、订货单作为交付凭证,并保证货物的实际交付。

“拾伍”普洱茶生产厂家广州市斗记茶业有限公司也发布声明称:“斗记从未生产及销售任何以‘理财’为功能属性的产品,市场上出现的该类产品均与斗记无关,属于个人行为。”并呼吁茶叶爱好者谨慎投资,警惕非法集资、诈骗、非法期货交易等违法违规行为带来的风险。

从大益茶到昌世茶,“金融茶”的前世今生

金融茶,顾名思义就是“炒茶”,厂商通常将某个品牌的茶叶包装为具有很高的收藏和投资价值,然后通过造势、捂盘限量投入市场,拉长战线,拉升价值感,分阶段进行品相叠加,最后高位抛盘,提现走人。

“金融茶”玩法和金融产品类似,带来的刺激感也和股市类似。

而这种玩法早在2000年前后就已经出现,而事件的中心也是广州芳村。

2007年初,云南茶叶原料价格达到顶峰,炒家们买进卖出以拉升价格,制造着普洱茶市场的虚假繁荣。这种繁荣的景象也吸引了不少普通人入局,但2007年6月,庄家把茶价抬高的同时悄然抛货,大茶商也跟着抛货,普洱生饼一夜暴跌,大批茶商关门跑路,千万级市场就此崩盘,不少普通人血本无归。

最近一次关于普洱茶的暴涨暴跌是颇有名气的“大益茶”。

据中新经纬报道,云南大益茶业集团有限公司始创于1940年,其出品的普洱茶按照年份、批次、规格等不同分为千余种。大益集团前掌舵人吴远之在2004年率团队收购勐海茶厂后,开创性采用“期货交易”模式运作,普洱茶的收藏和金融属性被放大。

2021年3月,大益茶的市场价格一路上涨,一款2003年的“班章六星孔雀青饼”价格甚至达到了6500万元/件的“天价”,“有价无市,一茶难求”。但同年8月起,以大益茶为代表的“金融茶”进入一轮深跌,至2022年8月今仍“跌跌不休”。普洱茶市场爆雷,众多在金融茶“期货市场”上做空的商家血本无归。全国茶叶商协会、广州茶协会、东莞茶协会等也曾联合发布“天价茶”抵制书。

但追逐“金融茶”带来的快感却从未因一次次现象级暴雷事件消退,类似的事情却总在芳村反复上演。

加速“收割”,当“金融茶”碰到“互联网”

虽然万变不离其宗,但本次的昌世茶事件却依然有不少“时代特色”。

以往“金融茶”布局往往周期在一年以上,有的甚至会将展现尽量拉长,比如2009年前后芳村开始炒作“古树”概念,2009年,芳村推出了名山和古树茶的概念,很多普洱茶新品牌,经过4年的炒作运转,2013年名山茶和古树才进入爆炒期,几万元一饼的新茶层出不穷。2014年,古树茶概念才开始暴跌。

然而在昌世茶事件中,该公司成立于2023年6月5日,整个炒作周期甚至只有两个月,今年9月20日,昌世茶举办开幕仪式,相关产品的宣传才正式开始。各种行情信息通畅在微信群中传播,非常隐蔽。

虽然芳村“茶商”深谙此道,但与此同时也不乏赌徒心理,据每日经济新闻报道,虽然微信群“叫价”,但往往真正的“买货”都需要私聊,在全部交易过程中,这些人不会在微信群里输入“一个月保证价格升多少”“以多少钱进行回收”“做期货买卖”等字眼。11月底开始,群风向突变,一片喊涨的微信群开始逐渐有人低价出货,当不少茶商醒悟之时已经不再有人愿意接盘。

找找茶品牌网数据显示,12月3日左右昌世茶开始价格暴跌,昌世通济跌约30%,昌世亨泰跌超43%。

翟山鹰:公共骗子?

“大家好啊,从去年我离开中国到今天,有一些人在网上说我是个骗子。我是做了十几年的金融,在这个环境里大家知道金融嘛几乎都是骗子,身边都是骗子。”

然后他话锋一转,赞扬起了自己的智慧,嘲讽起了那些被骗的人们。

“如果有人说我是个骗子,我是挺高兴的。你被骗了,你又不是被抢了,不是被强制性的。你让我骗了以后,你肯定还会被很多比我更有智慧的人骗。我是没有听说过特别蠢的人能骗到有智慧的人的,都是有智慧的人去骗蠢人。”

一个逃到美国的金融大骗,在公共平台的视频中得意洋洋地讲述着自己的经历。这个被一些粉丝视为“神一样的男人”的高论震碎了大家的三观,也震碎了仍然抱有幻想的粉丝。

自从去年他卷钱跑路之后,多数人便看清了现实,但仍有少些人觉得事有蹊跷。“他是说真话得罪了太多人,被人陷害了。”

为什么他跑路之后,仍然有粉丝执迷不悟地维护他呢?因为他的人设实在太耀眼。

他的名字叫翟山鹰。

他甚至可以称之为“中国最著名的金融防骗专家”。你没有看错,这位金融大骗,是专业防骗的。他全网粉丝近千万,还出版过多本大作:《中国金融生态圈》《金融防骗33天》《中国式融资》《资本内幕》。

说不定你或身边的朋友,就读过他的作品。翟山鹰原名翟红鹰,出生于1970年的北京空军大院,家境不俗。

高起点的“红三代”翟山鹰,像雄鹰一样有着远大的前程。22岁大学毕业后,从乡镇企业城的主任助理开始,一步步爬到了高处。

2002年,仅仅十年时间,32岁的他就已经成为香港建银国际公司——中国分公司的总经理。这家公司主营投资银行业务,像什么企业融资、投资咨询、财务顾问等。

后来的他转战培训师领域,那时讲商业的很多,但讲金融的很少。讲金融的翟老师宛如鹤立鸡群,再加上雄辩的口才,在培训界名声渐起,吸引了许多忠实的学员。

2013年,有20名学员投资一千多万,开了家文化公司。他们决定让德高望重的翟山鹰老师出任董事长,带领公司扬帆起航。

结果,他们在满怀期望中,成为了第一批受害者。由于公司长久没有盈利,他们展开了调查,竟发现老师偷偷地又开了一家公司。

老师把培训所得的收入转到自家公司,所有的支出则走学员公司的账。如此一来,别说赚钱了,反背上600多万的债务。

由于过了诉讼时效,这600多万债务至今仍由学员们担着。学员之一的陈琪感叹:“他发家就是从我们开始,在我们之后才有资本越玩越大。”有了足够多的本钱后,翟山鹰如虎添翼,飞上苍穹俯视大地,成功升级成了更大的祸害。

2014年,翟山鹰又创立了一家公司——普华商业集团。以此为大本营,不断打造自己的帝国。

除了激昂的语调外,翟山鹰讲课还有三大特点。

一是胆大,传授企业经营的捷径。什么捷径呢,比如避税、用专利替代货币进行企业实缴注册资本。

二是接地气,能够将各种硬核的金融术语,讲得通俗易懂。比如他把银行贴现比作打白条,特别适合想要快速入门的客户学习。

三是传授防骗技巧,为此专门写了一本《金融防骗33天》的书。他不断地警告大家金融的邪恶,甚至采取咒骂的方式:“地狱十八层,最底下十层都住满搞金融的!”

由于他屡次在媒体上痛斥资本,许多粉丝怒赞他是“唯一敢说真话、神一样的男人”。翟山鹰并不满足于金融防骗大师的名号,又扛起了国学的大旗,蹭起了爱国的流量,并拥有一堆头衔。

他自称11岁开始修行国学智慧的门派自然禅,如今身价百亿全凭国学修行,现在是自然禅国学门派第18代传承者。

与此同时,他还直言当今的中国就是世界最强,美国则会在未来十年内崩溃。伴随着时间的推移,他对美国越看越衰,又坚定地把美国崩溃的期限定为六年、五年。

各种闪瞎眼的头衔就更不用说了,号称“唯一有资格竞争诺贝尔经济学奖的中国人”,还是多所顶级大学的客座教授(目前清华、北大、中央财经大学等高校已辟谣)。

这样一个正义、爱国、传承文化的金融大师,自然吸引了大量关注。他的微博粉丝数高达600万,抖音粉丝则超100万,再加上其他平台,全网粉丝接近千万。成为了他的粉丝,也就离被骗不远了。不过他就像张麻子一样,懒得挣穷人的钱。

根据北青报记者的采访,翟山鹰主要卖揭露“金融诈骗”的课程,售价高达5000元,以此吸引有钱的客户。

如果你以为翟老师志在卖课的话,那就太小看他了。卖课收入只是毛毛雨,更大的目的是为了筛选出财力雄厚的学员。对于这些优质学员,翟老师将亲自带他们飞。翟老师首先推出了SEA虚拟货币,官方介绍是:“SEA是全球唯一一条跟实体企业相关的公链,专门解决中小企业融资难的问题,数据和银行对接。”

而且,这个币被翟老师讲得比比特币还牛,年收益能达到16%。只要长期持有,财富就可增值十倍乃至百倍。

能轻松赚大钱,又能拯救中小企业,利国利民还利己,许多敬仰老师的学员果断买入。没过多久,翟老师又推出了基于区块链技术的BSC云盒。

这个云盒就更厉害了,号称“接入国家一带一路项目的云存储服务器”。只要往电脑上一插,它就能24小时不间断地产生SEA积分和虚拟币,都能增值和交易。

这简直就相当于摇钱盒啊,定价多少钱呢?SE版本是4.4万一台,全功能版本的则是8.8万一台,多买还能够打折。由于入局的学员越来越多,为了防止提现,翟老师一方面拔高提现门槛,又成立了许多小公司,让大家用积分购买公司股权,到时候将有更高的收益。

虚拟币、区块链,每一次翟老师都站在了时代的风口浪尖。学员们也满以为跟对了老师,依托最新的技术和政策,轻松地躺赚。

一位董姓学员表示,她累计投资了240多万元。仅仅是她所在的弟子群,就有大约5000多人,绝大多数人都投资了至少几十万。但令他们怎么也想不到的是,温和善良的翟老师,竟然会骗学生的钱。

2020年年底,有位曹姓学员突然发现,这个云盒产生的积分,根本在国际区块链交易系统查不到,而且积分竟然从高峰期的1.3元跌到了几毛钱。

她一怒之下拆解了几万买来的云盒,看到里面就是一个简陋的插卡硬件。送到专业机构检测后,发现没有任何区块链技术,就是一个跑分程序,成本只有100多块钱。

她把视频上传到网络后,许多人意识到被骗,于是联合起来维权,却遭到了普华商业集团的恐吓。

后来他们找到了“知名打假人”王海,通过王海的微博,防骗专家翟山鹰诈骗事件终于引发了广泛关注。“据受害者爆料,普华集团翟山鹰谎称投资其产品一年可获利10倍,2年能获利100倍,大肆诈骗,非法所得或高达数十亿。”

2021年5月,北京市公安局朝阳分局在接到群众举报后,正式对普华商业集团涉嫌诈骗事件予以立案。

在警方调查期间,翟山鹰见形势不妙,立即跑到了迪拜,然后辗转抵达了一直厌恶的、“即将崩溃”的美国。

到达美国的他,好像换脑一般,猛烈抨击起了中国。中国哪是什么世界最强啊,经济没救了,科技命门都在美国手里……

此情此景,或只能用上《三国演义》里的一句话:我从未见过如此厚颜无耻之人。高级的骗术,往往是七分真实,掺三分虚假。真真假假,假假真真,让人防不胜防。

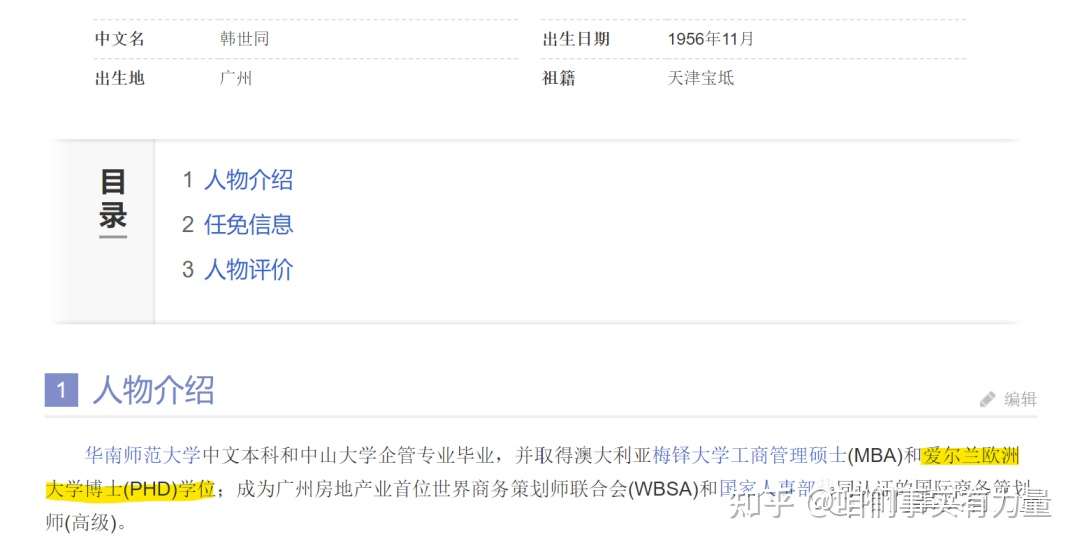

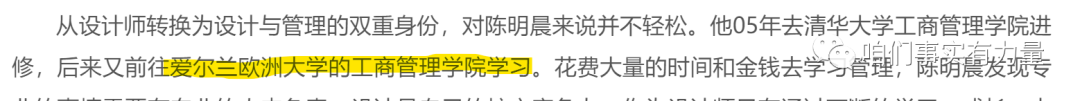

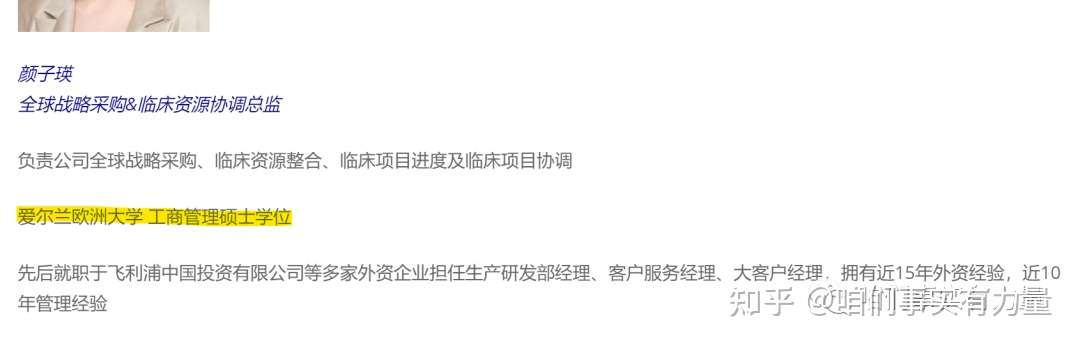

2022 陈春花们:真的假学位与假的真学位

2022年7月6日,华为公共及政府事务部在华为“心声社区”发布一则的辟谣声明,该声明称:近期网络上有1万多篇夸大、演绎陈春花教授对华为的解读、评论,反复炒作,基本为不实信息,我们收到不少问询,所以正式声明:华为与陈春花教授无任何关系,华为不了解她,她也不可能了解华为。

2022年8月3日,北京大学发布声明:近期,我校对陈春花老师的有关情况进行了调查。8月3日,我校国家发展研究院收到了陈春花老师的辞职申请。学校按程序终止其聘用合同。陈春花自述的“读博”经历

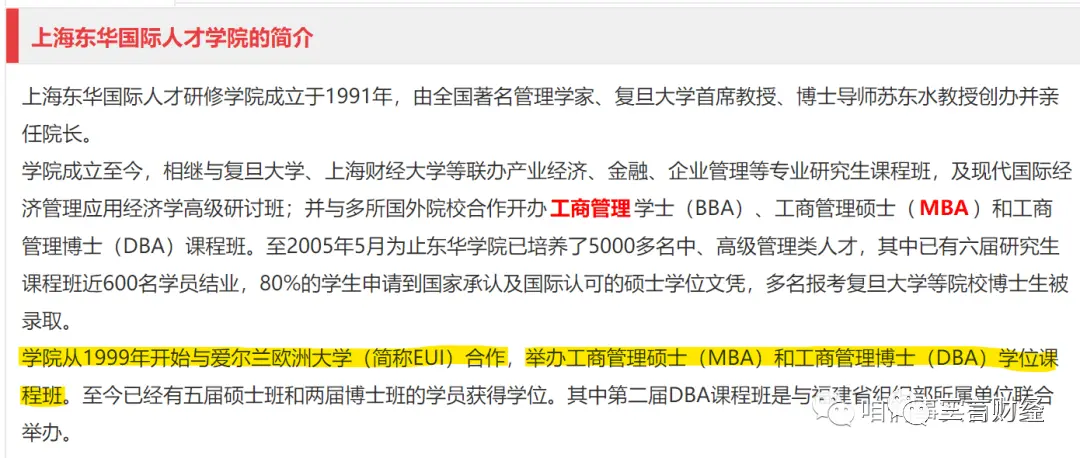

2021年6月16日,陈春花教授在自己的公众号发文《陈春花:悼念恩师苏东水先生》,描述了苏东水成为自己恩师的渊源。

陈春花在香港科技大学的一次研讨会上,结识了新加坡国立大学的曾在本老师,曾在本把她引荐给苏东水。

于是,陈春花作为晚辈,前往上海拜见已经是泰斗级的苏东水。

苏东水在家接待了陈春花。

这是陈春花第一次见到苏东水,谈的很好,苏东水很高兴,不但让太太留饭招待,而且主动提出,陈春花是否愿意当他学生?

苏东水说,刚好有一个论文博士的项目适合她,于是陈春花毫不犹豫接受了这个推荐,去读了。

她继续写到:倾听苏老师和复旦其他几位老教授的课程,让我从另外一个角度去看中国企业的管理。那么,接下来的问题,自然是,陈春花有可能就是这样“读博”拿到“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的假DBA博士吗?

显然,师从苏东水的“读博”,和假博士证有大背景的高度吻合。

首先,《陈春花:悼念恩师苏东水先生》,是她对外唯一正面讲述“读博”经历,可视为其唯一“读博”经历,而她只有一个“博士”头衔。经历和结果的唯一性吻合。

其次,时间背景高度吻合。她第一次见到苏老师,苏老师就向她推荐了“论文博士”课程项目。当时“苏老师还讲到了他从教40多年的心得”。

苏东水,复旦大学首席教授,复旦大学东方管理研究院名誉院长。据称为经济学家、管理学家,东方管理学派创始人。苏1956年9月起,在上海社会科学院、上海财经大学等单位任教。1972年1月进入复旦大学工作。2021年6月13日辞世,享年91岁。

故陈春花第一次见苏东水,对应时间是1997年(从教41年)-2005年(从教49年)。

她还写到:当时的苏老师已经是复旦大学的首席教授,自己还是一个很普通的年轻老师。她2000-2003年担任华南理工大学管理学院副院长,职称也是副教授/教授,已非普通老师。

故她第一次见苏东水,时间在1997-2000年。

陈春花读苏东水“论文博士”又是何时?她1999-2000年读新加坡国立大学EMBA,她不可能先读“论文博士”,再读EMBA,因而“读博”时间不会早于1999年。既然苏东水第一次见面就推荐她读“论文博士”课程,故她“读博”时间很接近,可以推断为1999-2001年。这和她读“爱尔兰欧洲大学”完全吻合。而她可能同时攻读两个“博士”吗?

苏东水推荐的“论文博士”课程是复旦大学的博士课程吗?很简单,如果是复旦大学的博士课程,那陈春花应该有2001年前后复旦大学的“论文博士”课程结业证书,或者复旦颁发的博士证,对吧。显然她没有。

以上是根据已知事实,用排除法,证明陈春花师从复旦名师苏东水读“论文博士”课程,和其假博士学历高度吻合。

那么,有没有直接的事实依据,可直接证明苏东水当时推荐的“论文博士”课程,就是“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的“博士”课程?

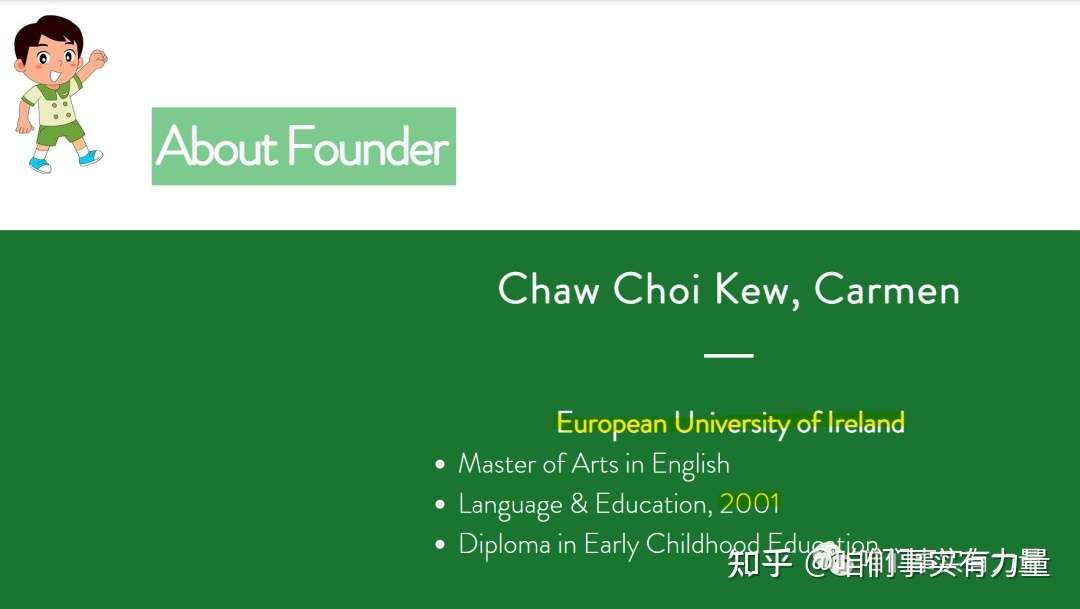

爱尔兰欧洲大学招生简章和课程表

“中国海峡人才市场”官网上“www.hxrc.com”,2022年7月还挂着“爱尔兰欧洲大学”2001年和2003年的工商管理博士班招生简章。

以上2003年招生简章截图网址是:“http://app.hxrc.com/services/news/wap/NewsDetail_26356.html”

再看2001年招生简章:

以上2001年招生简章截图网址是:“http://app.hxrc.com/services/news/wap/NewsDetail_18251.html”

这还没完,还有2001年的“爱尔兰欧洲大学”DBA博士课程表。

以上课程表网址是:“https://app.hxrc.com/services/news/wap/newssearch.aspx?id=18252”

这3份事实性材料,完整地反映了“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的“入学”条件、“课程”设置、收费标准和发“博士证”,揭示了“爱尔兰欧洲大学”在国内运作的关键事实:

无需入学考试,申请就行,在国内上课。福州“博士班”在福州上课。

2年学完,复旦和上海交大7个教授和博导到福州每月面授一次,还有2个“爱尔兰欧洲大学”“教授”。

凭博士论文通过答辩毕业,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”授予“博士证”。学费6万。

而且2003年招生简章还透露了,2001年的博士班一共有19人在读。这3份事实性资料,发布来源靠谱权威。根据发布网站官网介绍:中国海峡人才市场是福建省人民政府与原国家人事部于1998年1月在福建人才智力开发服务公司(1988年6月成立)基础上共同组建的国家级人才市场,是福建省人民政府所属的事业单位、综合性大型人才服务机构。是一家事业单位。发布网站:“www.hxrc.com”也确实是中国海峡人才市场的官网,有正式的备案号。具体的发布者是中国海峡人才市场下属的事业单位“福建省企业经营管理者评价推荐中心”。根据官网介绍,这是2000年1月由福建省委编办批准成立的事业单位,主要从事社会化考试、人才测评、管理咨询、经营管理人才评价、技能人才评价、人才背景调查以及研修培训等服务的专业机构。 至此可以总结,福建省企业经营管理者评价推荐中心只有人才服务职能,不可能和什么外国大学联合办学。它实际是在福州推销“爱尔兰欧洲大学”“博士”课程项目,也就是卖课。2001年还成功举办了1期,帮助19个学员在2003年拿到“博士证”。

“爱尔兰欧洲大学”福州博士班的课程表信息量也很大。所列教授名单:两个来自“爱尔兰欧洲大学”

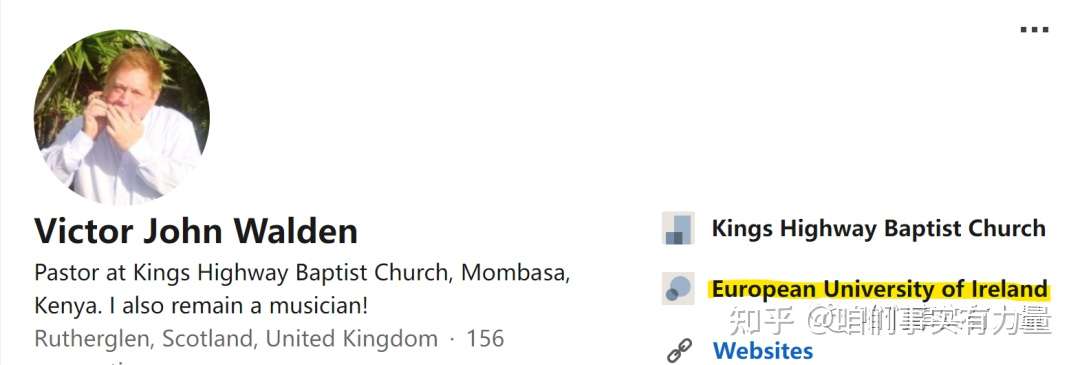

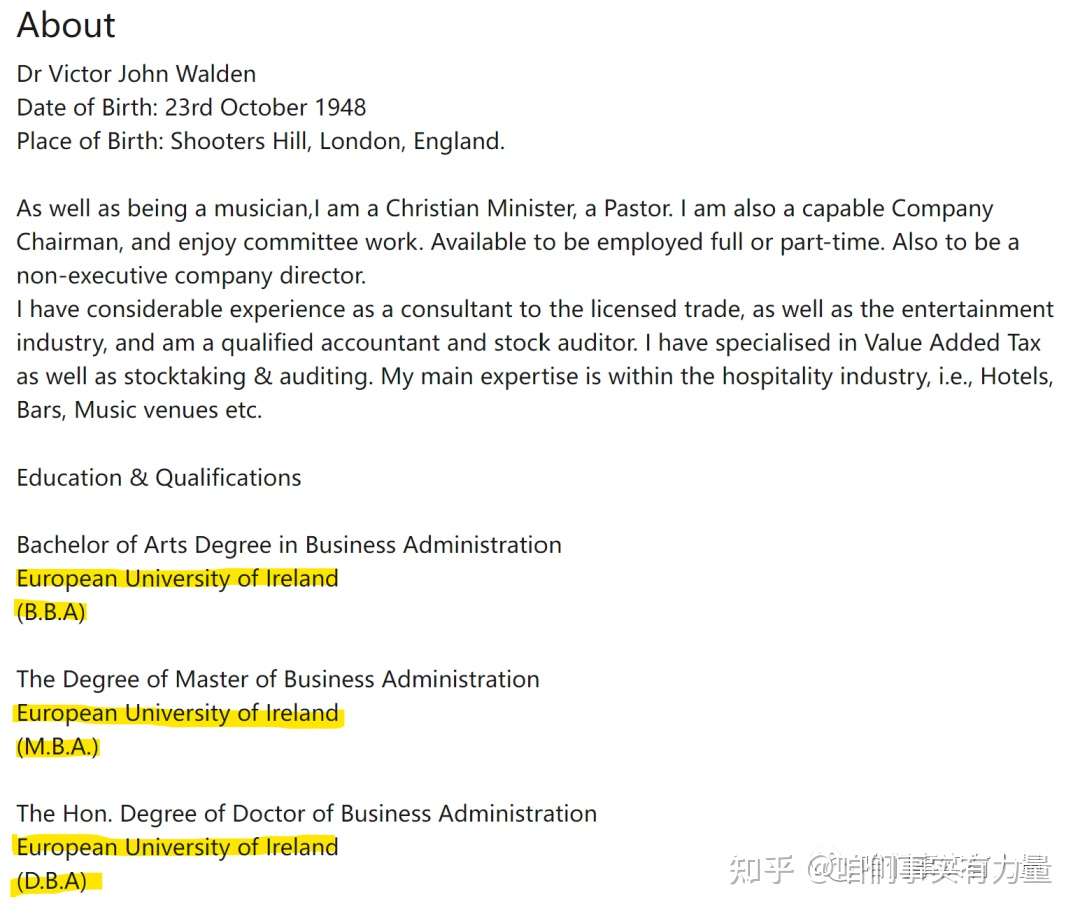

V.J. Walden教授,爱尔兰欧洲大学校友:自称是音乐家,牧师,公司董事长,本硕博在“爱尔兰欧洲大学”连读!他介绍自己的专长是服务招待行业,比如旅店、酒吧、音乐节等等,可以从事这方面的全职或兼职工作。这位在英国从事服务招待的绅士,2001年作为“教授”,和复旦、上海交大的教授博导一起,给中国学生上财务会计课!

Vale教授,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的老板之一

再看国内的教授,6个复旦大学的教授、博导,1个上海交大的教授、博导,阵容豪华!

一 管理经济学 孟宪忠教授、博导 上海交通大学管理学院

二 银行管理与货币政策 甘当善教授、博导 复旦大学经济学院

三 国际市场营销 薛求知教授、博导 复旦大学管理学院

四 组织行为与管理文化 苏 勇教授、博导 复旦大学管理学院

五 人力资源管理 张文贤教授、博导 复旦大学管理学院

六 企业策略与政策 胡建绩教授、博导 复旦大学管理学院

九 东方管理专题讲座

1 中国国民经济管理研究 芮明杰教授、博导 复旦大学管理学院副院长

2 企业创新 孟宪忠教授、博导 上海交通大学管理学院授课老师里并没有苏东水,为什么招生简历强调有苏东水? 苏东水和这个“爱尔兰欧洲大学”博士班有什么关系?

国内是谁和“爱尔兰欧洲大学”合作?

在“淘课网”“www.taoke.com”上,有一个“上海东华国际人才学院”,2006年发布了6个课程,分别是:

复旦大学职业经理人卓越领导与创新管理高级研修班,2000元。

国际商务与跨国经营(3月份公开课程),2400元。

东方精英大讲堂――合作与竞争,价格待定。

爱尔兰欧洲大学工商管理硕士MBA,45800元。

工商管理硕士对接班,32000元。

爱尔兰欧洲大学工商管理博士DBA,66000元(陈春花所读项目)。

以上截图网址:“https://www.taoke.com/company/1462/course”

上海东华国际人才学院自我简介是:

以上截图网址:“https://www.taoke.com/company/1462.htm”

学院从1999年开始与爱尔兰欧洲大学(简称EUI)合作,举办工商管理硕士(MBA)和工商管理博士(DBA)学位课程班。

这个上海东华国际人才学院,是什么机构?简单说,它是培训机构。但地位特殊,因为它是苏东水1991年创立并担任院长,某种程度可以把它比作苏东水的化身。

自1997年开始,由世界管理学者协会联盟(IFSAM)中国委员会、复旦大学东方管理中心、复旦大学经济管理研究所、中国国民经济管理学会、上海管理教育学会、上海东华国际人才学院等机构组织每年举办一次“世界管理论坛及东方管理论坛”,先后在复旦大学、上海外国语大学、上海交通大学、北京大学、河海大学、法国国立艺术及文理学院、国立华侨大学、上海工程技术大学及东华大学等国内外知名学府,举办了23届世界管理论坛暨东方管理论坛,

以上内容出自世界管理论坛暨东方管理论坛简介:“http://www.omforum.cn/portal/Page/index?id=3”

上海东华国际人才学院可以和众多一流大学、官方机构一起举办学术研讨活动,地位可见一斑。

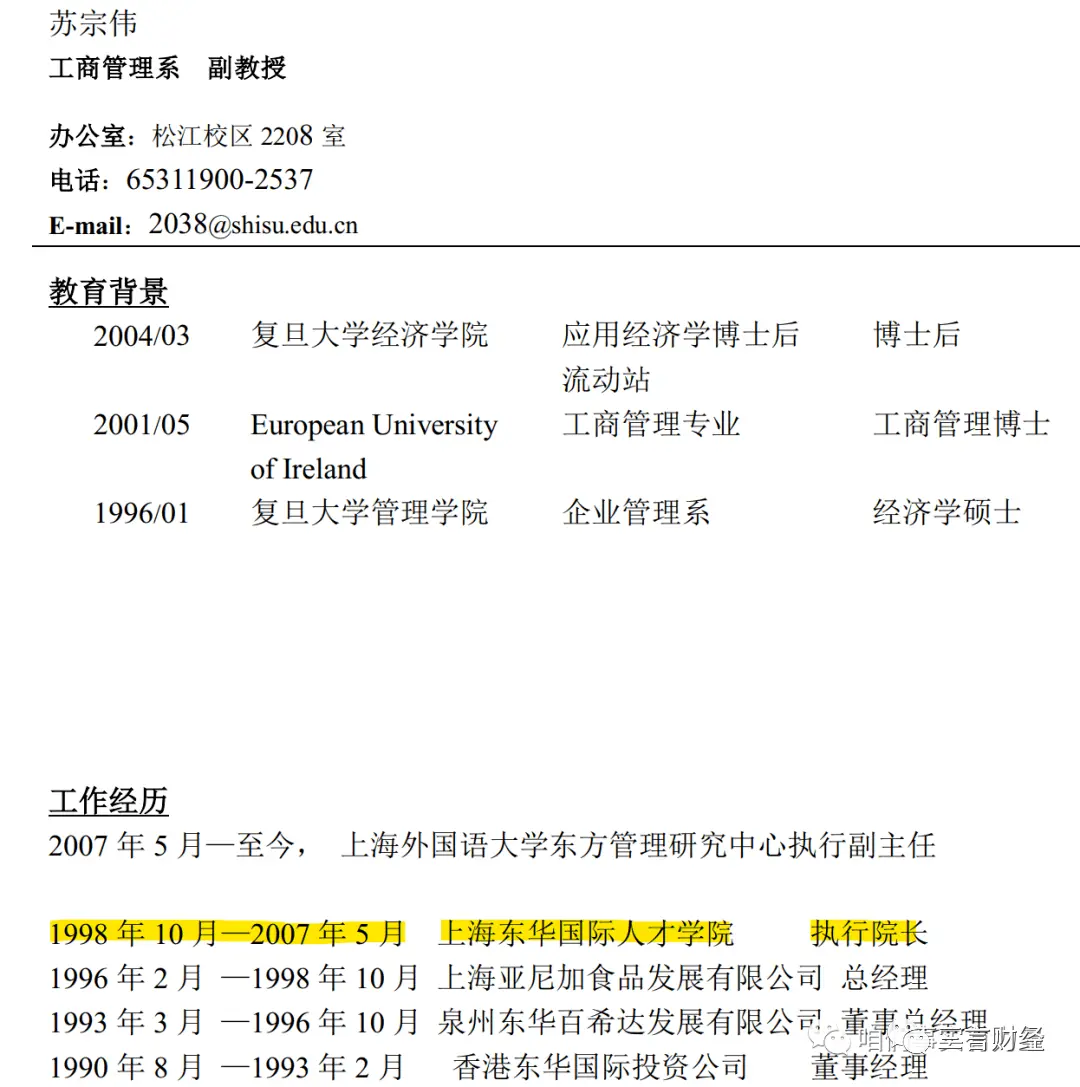

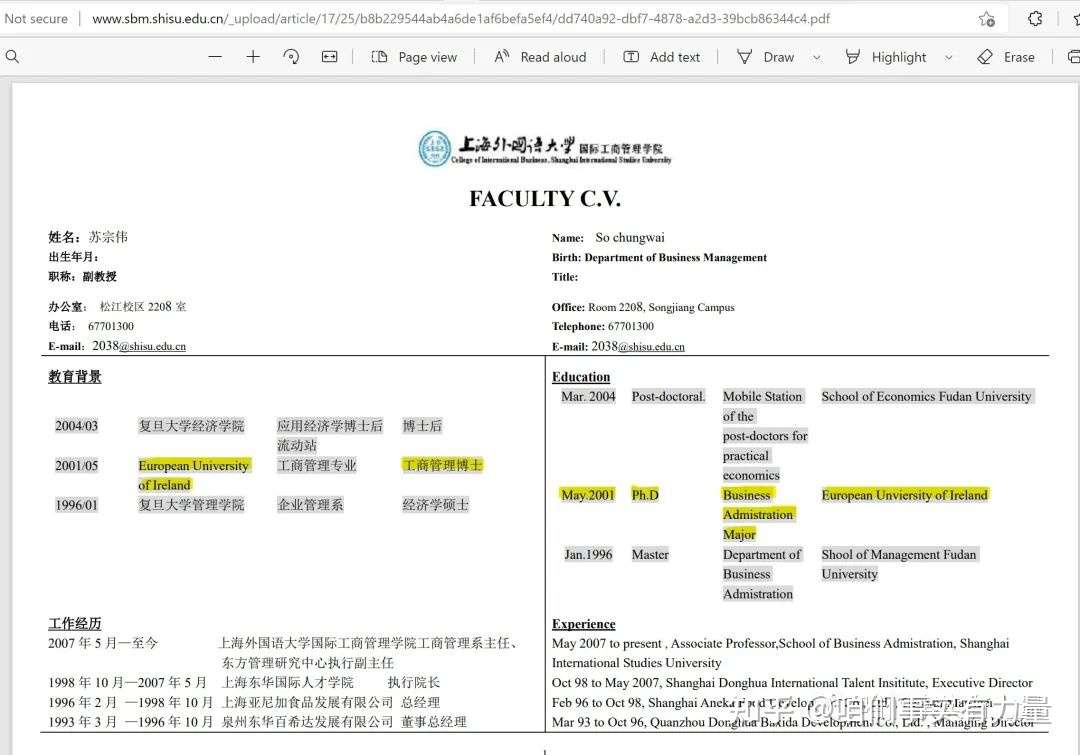

虽然苏东水担任上海东华国际人才学院院长,但1998-2007年期间,苏东水的儿子苏宗伟,担任上海东华国际人才学院的执行院长。

这个苏宗伟就是《(更新)陈春花教授都有哪些“爱尔兰欧洲大学”校友?上海教授,职场精英,还有一个假民校?》里第一位校友,上海外国语大学工商管理系主任、东方管理研究中心执行副主任。

也就是说,执行院长苏宗伟才是上海东华国际人才学院的实际操盘者。

他1998年10月担任执行院长,而1999年上海东华国际人才学院就和“爱尔兰欧洲大学”就开始合作。

如果这就是最终谜底,那么,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”所有事情都可以完美解释了。

虽然没有资料可以看出,上海东华国际人才学院和“爱尔兰欧洲大学”是如何在1999年走到一起的。但闭着眼睛也可以料想执行院长苏宗伟独一无二的优势。毕竟父亲苏东水会信任和帮助儿子的,对吧。

借着苏东水的旗号和影响力,一般人办不了的事不再是难事,包括轻松组织起复旦和上海交大的豪华“授课”团队,找到福建省企业经营管理者评价推荐中心卖课。苏东水是泉州人,1987年牵头发起了上海泉州侨乡开发协会,在福建和泉州的影响力也非常大。

DBA课程表名单里的7位教授,有确切资料可查的,其中3位教授是苏东水的学生,1位教授是他的好友。

上海交大孟宪忠教授、博导,1995年-1997年在复旦大学师从苏东水教授做经济学博士后研究。

以上截图网址:“https://www.sohu.com/a/253292137_488818”

复旦教授甘当善,是苏东水好友。

以上截图网址:“http://www.fudanpress.com/news/showdetail.asp?bookid=11518”

复旦苏勇教授,1991年考取苏东水的博士生。

以上截图网址:“https://www.fdsm.fudan.edu.cn/anniversary30/30th1393503572878”

复旦芮明杰教授,是苏东水的硕士生和博士生。

以上截图网址:“https://weibo.com/p/100202read7317420/author?from=page_100202&mod=TAB”

第四块拼图:淘课网上的“上海东华国际人才学院”可能被冒名吗?

和中国海峡人才市场网发布的“爱尔兰欧洲大学”招生简章、课程表不同,上海东华国际人才学院与“爱尔兰欧洲大学”合作办学的信息,并非发布于这个学院的官网,而是发表于“淘课网”。在淘课网上,任何培训机构都可以发布培训课程信息。

有可能是上海东华国际人才学院被人冒名顶替,发布了假大学的课程?

理论上可能被冒名,但大量课程细节证据显示不太可能被人冒用,它应当就是本尊。

淘课网上,上海东华国际人才学院2006年发布了6个课程,除了2个“爱尔兰欧洲大学”课程,还有4个其他课程。

复旦大学职业经理人卓越领导与创新管理高级研修班,2000元。

东方精英大讲堂――合作与竞争,价格待定。

国际商务与跨国经营(3月份公开课程),2400元。

工商管理硕士对接班,32000元。

这些课程与上海东华国际人才学院的实际日常活动完全吻合。

首先看“东方精英大讲堂”课程。

以上截图网址:“https://www.taoke.com/opencourse/7897.htm”

根据课程描述,上海东华国际人才学院自2006年3月至12月,每月举办一期“东方精英大讲堂”系列活动,可以给报名企业提供冠名机会,和一定数量入场券,相关活动在“三报两台”报道。活动结束后,复旦大学出版社会结集出书。

根据百度百科,复旦大学出版社的确在2006年11月,对“东方精英大讲堂”活动出版《东方精英大讲堂:领先与创新专题》,编著者正是苏宗伟。

《东方精英大讲堂:领先与创新专题》一书的内容,正是来源于“东方精英大讲堂”组织的学术报告记录,付诸出版之前,演讲者对记录稿做了较大修改补充。

再看“复旦大学职业经理人卓越领导与创新管理高级研修班”课程。

以上截图网址:“https://www.taoke.com/opencourse/8252.htm”

这个课程指出,可以通过“东方管理论坛”、“东水同学会”等资源,为学员搭建沟通交流平台。而前面的资料拼图里已经讲过,上海东华国际人才学院地位特殊,可以和一流大学以及官方机构合办“东方管理论坛”;“东水同学会”也是依托上海东华国际人才学院运转的苏东水学生群体。

以上截图网址:“http://www.donghuaxueyuan.org/dsac_detail.asp?id=41&type=8”

“东方精英大讲堂”和“复旦大学职业经理人卓越领导与创新管理高级研修班”这两个课程具体内容,和上海东华国际人才学院的日常活动完全一致,足证在淘课网里发布这些课程的是其本尊。

而且,在一个标注为上海东华国际人才学院的网站上,其课程栏目也列出了“东方精英大讲堂”和“复旦大学职业经理人卓越领导与创新管理高级研修班”。

以上截图网址:“http://www.donghuaxueyuan.org/lj.asp?id=13&type=4&pageno=4”

再仔细看,上海东华国际人才学院在“淘课网”的自我简介,甚至有更多彩蛋。

以上截图网址:“https://www.taoke.com/company/1462.htm”

彩蛋两处。首先独家透露了上海东华国际人才学院和“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的合作始于1999年,这个时间节点是全网独一份的信息。第二处彩蛋,就是透露了“第二届DBA课程是与福建省组织部所属单位联合举办”。这个信息,恰好完全吻合前面所列的2003年招生简章内容。

根据2003年招生简章,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”DBA“博士”课程为期2年。1999年-2001年是第一届(陈春花和苏宗伟读的就是这第一届);2001-2003年,是第二届。这第二届就是福建省企业经营管理者评价推荐中心卖出的福州课程班,一共19人参加。

试问,除了上海东华国际人才学院的真身本尊,谁还能编出这些真实准确的课程详情呢?

还可以从反面假设:有人2006年“冒用”上海东华国际人才学院名义在淘课网上发布虚假课程,想诈骗钱财。按照淘客网上的数据显示,这些课程的人气值(大概率是浏览量)都是好几千,如果真有人被这些“冒牌”课程骗去财物,从几千到几万元不等,受害者早就举报了,这些“冒牌”课程也早就应该被网站封禁下架了。

这些课程从2006年发布至今已经16年了,仍然完好地存在,也从侧面说明这些课程是真实有效。

上海东华国际人才学院

上海东华国际人才学院成立于1991年,2001年10月办理工商登记,登记名称为上海东华国际人才研修学院。官网是“www.donghua.org”

实际上,上海东华国际人才学院和上海东华国际人才研修学院,这两个名字平时都是混着用。苏宗伟在个人简历上就写的是上海东华国际人才学院的执行院长。

很凑巧,它官网“www.donghua.org”最近不能访问了,在本号7月13日发出《(更新)陈春花教授都有哪些“爱尔兰欧洲大学”校友?上海教授,职场精英,还有一个假民校?》,当时还能正常访问。

不过除了这个官网,还有两个网站可以参考。“www.donghuaxueyuan.org”,“www.dhiti.org”,都写着上海东华国际人才学院。

以上截图是“www.donghuaxueyuan.org”

以上截图是“www.dhiti.org”

这两个网站一模一样。

按照这些网站对上海东华国际人才学院的介绍,它“与国外院校合作开办工商管理硕士(MBA)和工商管理博士(DBA)学位课程班”。

这个和“国外院校合办工商管理硕士MBA和工商管理博士DBA学位课程”是不是很熟悉?这个国外院校又是哪个国外院校?

按照工商管理登记,上海东华国际人才学院只能从事非学历教育,它如何可以开展所谓的学位课程班?

“www.donghuaxueyuan.org”,“www.dhiti.org”,两个网站都有备案号:沪ICP备06003293。但这个备案号是2006年的备案号,现在已经失效,没有备案数据可查。

这两个网站和官网“www.donghua.org”是什么关系?

由于官网“www.donghua.org”暂时不能访问,暂时无法对比。

但初步分析,“www.donghuaxueyuan.org”,“www.dhiti.org”两个网站,可能是“www.donghua.org”的备份网站。

如果有什么不轨之徒想要冒充上海东华国际人才学院,发布课程,假冒网站,诈骗钱财,按照上海东华国际人才学院的特殊地位,那些山寨版的不轨之徒一经查实,早就会被有关部门依法查办了,对吧。

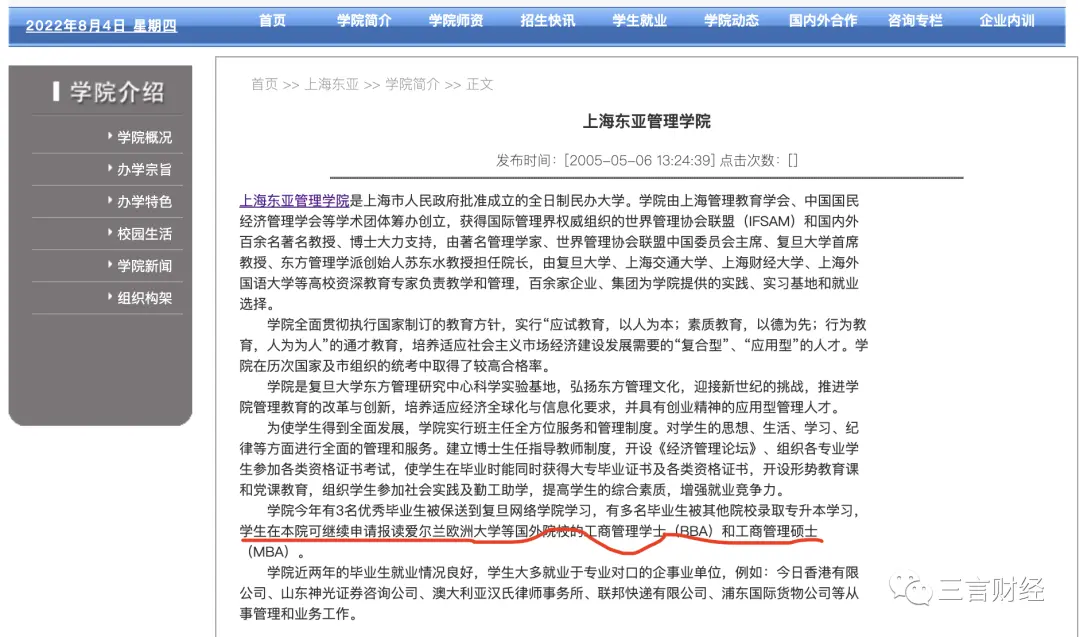

上海东亚管理学院

苏东水还曾经创办过一个“上海东亚管理学院”,工商注册时间为2001年4月,后来注销了。从注册信息看,这个东亚管理学院是民办大学,主管单位是上海市教育委员会。

而这个上海东亚管理学院,也有一个网站:“http://www.sheac.org/index.html”

在这个上海东亚管理学院网站上,也介绍自己是全日制民办大学。

以上截图网址:“http://www.sheac.org/introduction/4394510.html”

就在这个介绍里,我们又看到了熟悉的那个外国大学。

上海东亚管理学院的学生“在本院可继续申请报读爱尔兰欧洲大学等国外院校的工商管理学士(BBA)和工商管理硕士(MBA)”。

按照这个介绍,东亚管理学院和“爱尔兰欧洲大学”也有某种合作关系。但暂时不能确认这个网站“www.sheac.org”就是上海东亚管理学院的官网。

上海东华国际人才学院,上海东亚管理学院,这两所原本都是苏东水创办(具体运转未必是苏东水亲自过问)的机构,都可以报读“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的课程呢?可以确认的事实是,上海东亚管理学院后来在2009年终止办学了。

以上截屏网址:“https://xxgk.shu.edu.cn/info/1338/1373.htm”

在上海大学的官网上只有这个终止办学的标题,没有具体文件内容。

为何是上海大学发出民办东亚管理学院的终止办学公告?东亚管理学院是依托上海大学办学吗?

上海东亚管理学院为何终止办学?

而这个终止办学,有可能会和“爱尔兰欧洲大学”这个假大学有关系吗?

这些问题就不得而知了。

总结

根据以上六块拼图的资料,可以确认无可辩驳的事实有:

“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的MBA硕士班、DBA博士班,当时都是在国内开班。

DBA博士班,是组织了以复旦大学教授博导为主的授课队伍。(实际上课情况是否按照课程表开展,这个无从考证)

DBA博士班,学期2年。1999年-2001年是第1批,毕业生代表有陈春花和苏宗伟;2001-2003年是第2批,在福州开课,有19人;2003-2005年是第3批,是否办成,不得而知。

可以有较大理由认为成立的事实有:

“爱尔兰欧洲大学”在国内的合作方有上海东华国际人才学院。具体操盘是它的执行院长苏宗伟(苏东水之子)。这才能解释“爱尔兰欧洲大学”那时的组织“办学”能力,和收割能量。

陈春花的“读博”经历,也完全吻合了以上这些事实,和有较大理由可以成立的事实。

那么接下来,大家显然可以提出的问题是:所有这些曾经的参与者,授课教师,学员教师,职场精英,从头到尾没有怀疑过,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的真实性吗?这些所谓硕博学位课程授予硕博学位,真地合法合规吗?

一群以研究企业管理、商业管理为业的一流大学专家教授,最后竟然是参与了一个并不高明的假大学的课程,这是何等巨大的讽刺和伤疤。

“爱尔兰欧洲大学”一段荒谬的往事

2000年英国《泰晤士报高等教育副刊》就曾报道,爱尔兰教育部门正在调查一个未经官方批准就自称为“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的机构的运营,这个机构在爱尔兰首都都柏林的一个宿舍地址运营。“爱尔兰欧洲大学”在英国和国际上做广告,招收研究生学历以上的学生,但实际上从未向爱尔兰官方申请“大学”身份的许可。

另外,2005年,爱尔兰共和国《独立报》曾经揭露了三家贩卖学位的野鸡大学,其中有一家就是“爱尔兰欧洲大学”。

在国内,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”也没有被官方认可。教育部今年3月更新的爱尔兰高校名单中,总共有25个大学,并没有“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的身影。

根据爱尔兰工商查询网站的信息,“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的注册时间是1997年6月26日,注销时间为2010年8月20日。不过它的全称是“爱尔兰欧洲大学有限公司”,仅仅是名字看着像一所高校。“爱尔兰欧洲大学”的经营者们有4家共同拥有的公司,但如今没有一家公司存续。

就是这样一家机构,如何与国内知名大学的教授挂上勾?苏东水扮演了重要角色。

除了是复旦教授,苏东水还是一家教育机构的法人,这家机构名字为上海东华国际人才研修学院。而这个名字也将苏东水和爱尔兰欧洲大学紧密联系到了一起。

苏东水成立两家教育机构均与爱尔兰欧洲大学紧密相关

2006年上海东华国际人才学院曾在淘课网上发布过6个课程,同时该网站上还有上海东华国际人才学院一段介绍。介绍中指出,上海东华国际人才学院从1999年开始与爱尔兰欧洲大学(简称EUI)合作,举办工商管理硕士(MBA)和工商管理博士(DBA)学位课程班。

以此来看,陈春花是上海东华国际人才学院与爱尔兰欧洲大学合作的第一届博士生。

“上海东亚管理学院”号称是经过批准的民办大学,堪称互联网化石,最后的更新日期似乎是2013年。

上海东华国际人才学院全称就是上海东华国际人才研修学院,由苏东水成立。苏东水的儿子苏宗伟从1998年到2007年在上海东华国际人才学院担任执行院长。

也就是说苏宗伟1999年在爱尔兰欧洲大学攻读博士时,同时是这所“大学”的管理者。

上海东华国际人才学院官网www.donghua.org,目前已经无法打开。

另外,苏东水还在2001年成立过另一家教育机构东亚管理学院,不过该学院已经注销。

东亚管理学院的网站还在。其学院简介上有这样的表述:学生在本院可继续申请报读爱尔兰欧洲大学等国外院校的工商管理学士(BBA)和工商管理硕士(MBA)。

上述两所机构都是苏东水创立,一个合作举办爱尔兰欧洲大学的相关课程,一个可以申请报读。

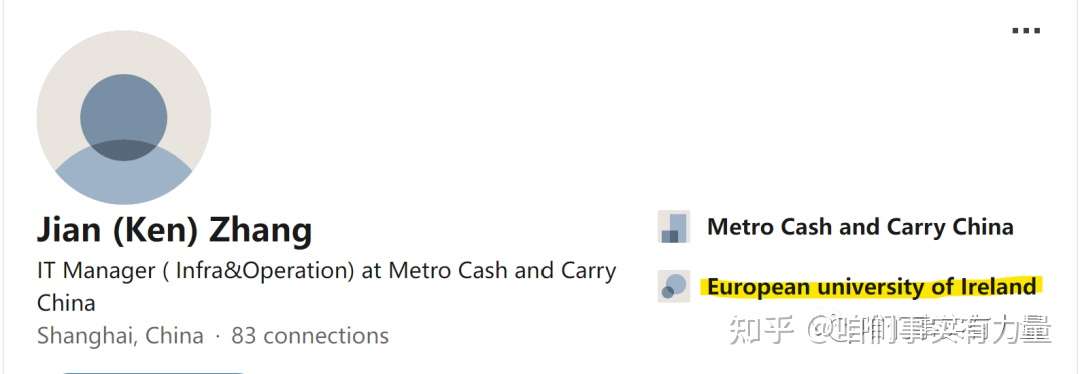

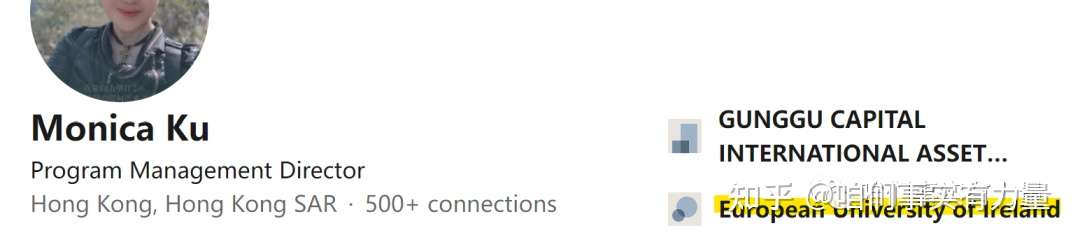

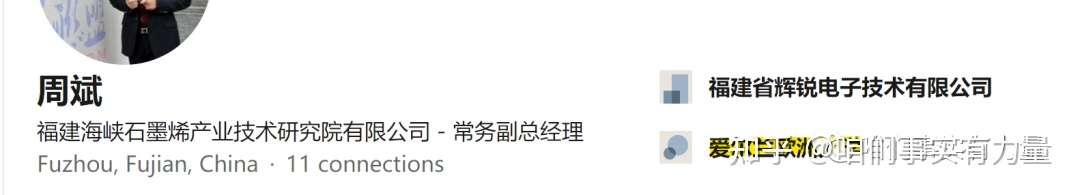

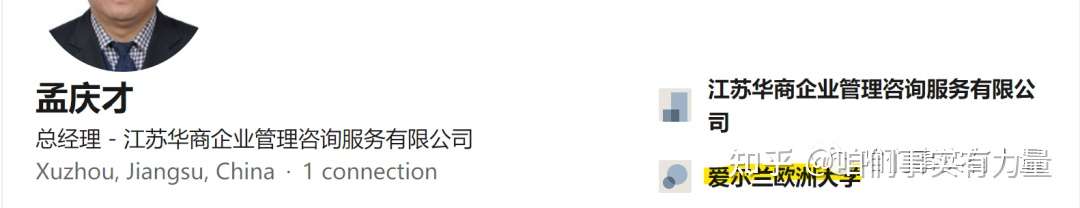

爱尔兰欧洲大学的博士校友们

校友一 上海外国语大学苏宗伟教授

陈春花教授的正宗同期校友:上海外国语大学工商管理系主任、东方管理研究中心执行副主任苏宗伟教授。2001年荣获“爱尔兰欧洲大学”工商管理博士学位,和陈春花教授正宗同期校友。

以上苏宗伟教授的简历地址是:“

http://www.sbm.shisu.edu.cn/_upload/article/17/25/b8b229544ab4a6de1af6befa5ef4/dd740a92-dbf7-4878-a2d3-39bcb86344c4.pdf”这位苏宗伟教授简历更大胆,直接在英文页上写自己是Ph.D。(Ph.D全称是哲学博士,是学历架构中最高级的学衔,是学术研究型博士,一般采用全日制学制。DBA工商管理博士学位,属于在职非全日制学制,是工商管理领域最高层次的学位教育项目。)

校友二:华东政法大学商学院陈燕教授

陈燕教授在学校官网的简历地址::“

https://sxy.ecupl.edu.cn/2792/list.htm”校友三:香港人陈之望

这位同学的“爱尔兰欧洲大学”“博士证”收获于2007年,在香港当过香港名校培正中小学及幼稚园校监(校长)。

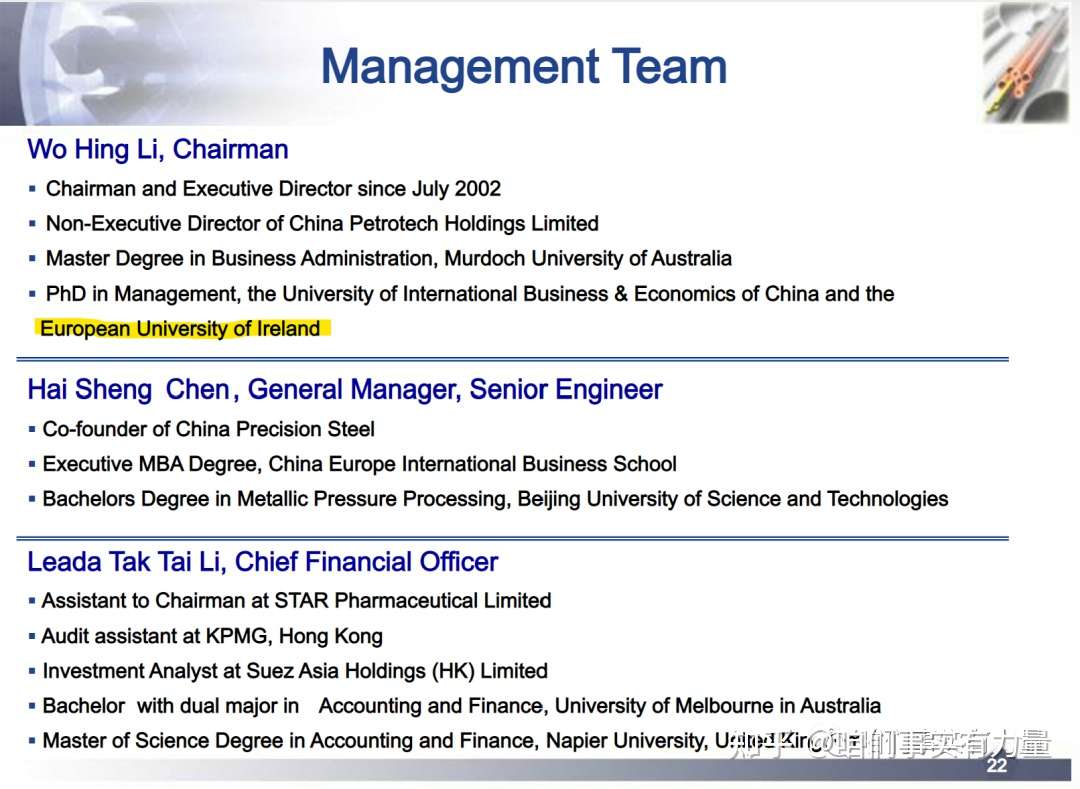

校友四:以前纳斯达克上市公司(代码CPSL)前CEO Wo Hing Li

这应该是个香港人。

校友五:一位捣鼓类似爱尔兰欧洲大学业务的英国“教授”

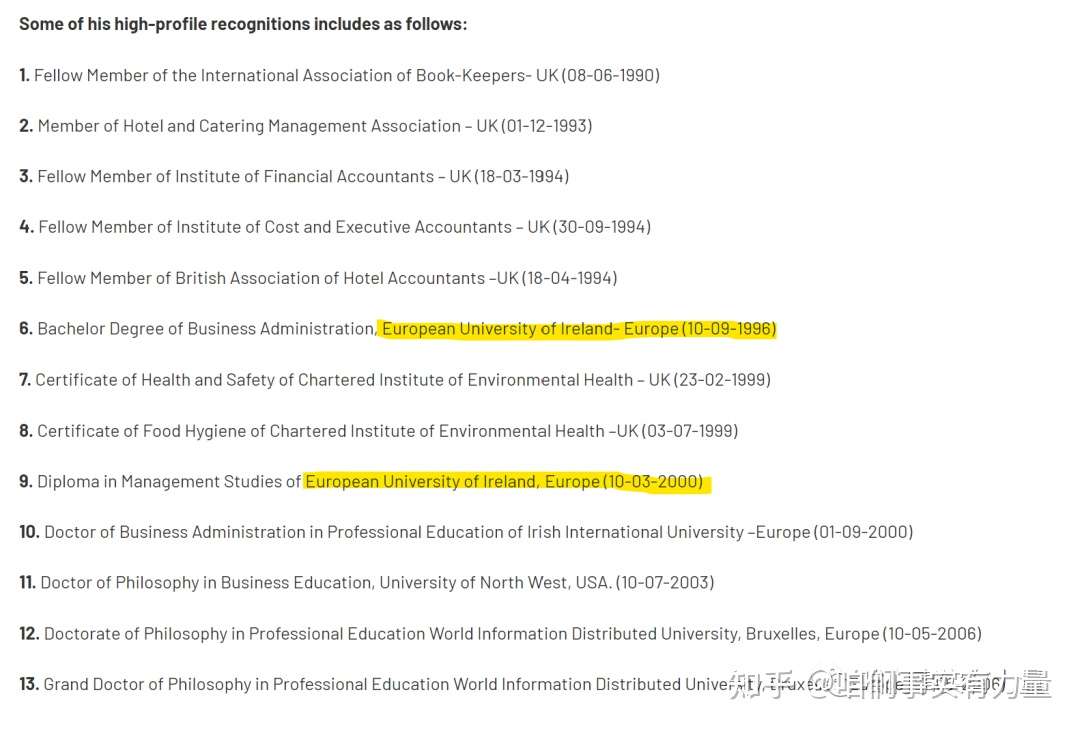

这位拿了13个学位,其中2个来自“爱尔兰欧洲大学”,比陈春花教授还早一年。

校友六:一位英国绅士

在爱尔兰欧洲大学一路从学士读到了博士。

校友七:马来西亚一位幼儿园园长

这位园长一口气从爱尔兰欧洲大学拿了三个证书。

更多校友:职场精英

上面这个截图的网址是:“http://qccdata.qichacha.com/ReportData/PDF/560c6e31994933a9704139759091524d.pdf”,是企查查发布的一个企业的董事换届公告

爱尔兰欧洲大学复旦大学分校?这也太没边了吧,假证上也不至于这么写吧?

上面截图网址:“http://www.shm.com.cn/2018-07/25/content_4745852.htm”

王靖:从洗浴中心到尼加拉瓜大运河

王靖1972年12月出生,被称为“中国最神秘的商人”,其履历及财富来源,一直像一个谜。王靖出生于北京,父母都是工人;由于成绩一般,大学就读于江西中医药大学中医专业。王靖大学还没毕业就回到北京寻找机会,时值1993年,他在北京开了个洗浴中心,取名为“北京昌平传统养生文化学校”。其时,养生是新鲜概念,21岁的他出任北京昌平养生学校校长。

90年代末,王靖关了他的洗浴中心,去香港先后开了香港鼎福投资集团、香港宝丰黄金有限公司和中国新华国安科技有限公司等数家公司,接着又去到柬埔寨开金矿。虽然王靖所开的公司全部倒闭了,但他对金融市场有了丰富的了解。1998年,他回到北京创立了一家投资咨询公司。

王后来接手了信威集团外,也是天骄航空、香港尼加拉瓜运河开发投资有限公司、中国海外安保集团董事长。柬埔寨的30亿订单

1995年,王靖还在开着洗浴中心时,“巨大中华”之一的大唐电信成立了北京信威,立志把信威打造成中国的高通。信威首任董事长是被称为中国“3G之父”的李世鹤,信威研发了SCDMA、TD-SCDMA和McWiLL三大国际无线通信技术标准,拥有TD-SCDMA技术标准下14项核心专利中的6项。2006年开始,北京信威因经营不善,连年亏损。2009年,大唐电信决定甩掉这个包袱。王靖抓住该机会,以8800万元的价格控制了信威41%的股权,成为信威第一大股东,出任信威集团董事长。

当时信威债务累累,房租和水电都交不起,门口每天都是讨债者。王靖上任后,第一件事就是从柬埔寨获得了一笔30亿的电信设备订单。信威赚了5.7亿,还清了债务,当年盈利3800万。在获得柬埔寨订单之后,信威集团先后获得了乌克兰、俄罗斯、尼加拉瓜、坦桑尼亚等国家的大宗电信设备订单。2012年上半年,北京信威和尼加拉瓜政府签了一份价值超过3亿美元的合作协议,获得在尼加拉瓜建设并运营覆盖全境的McWiLL公众通信网络和行业专网。一时间,信威的业绩亮眼。同期的标杆电信企业中,中兴的毛利率才到30%,华为也不过40%,而信威却高达88%。因以前的国企背景,信威不仅很快获得了进入特种行业所需要的相关许可证,而且还获得了工信部为其分配的应用频段。

王在接受采访中多次表示,自己在越南和柬埔寨淘金,两个国家都有金矿、宝石矿等矿业投资,光是金矿估值就有50亿美元。

不过,后来被发现是一个骗局,这个信威的柬埔寨客户,就是信威子公司重庆信威设立的分公司。信威与柬埔寨信威先签订一份30亿的设备订单,然后信威用现金等做抵押,向国开行申请一笔30亿的贷款,柬埔寨信威用这笔钱来向信威支付货款。而接盘柬埔寨信威这家公司的实际控制人,只是一个代办注册公司业务的越南人,注册花费了2000瑞尔(柬埔寨货币,约合5元人民币)。

6年发射32颗卫星

2010年信威与清华大学共同发起“清华—信威空天信息网络联合中心”项目,王靖出任管委会主席,合作研制灵巧通信卫星。2014年9月4日卫星成功发射,主要用于卫星多媒体通信试验,这个卫星被誉为“中国民企第一星”。王靖对外称将在六年之内发射至少32颗卫星,组成全球无缝覆盖的通信卫星星座,此时,马斯克的SpaceX公司才刚刚起步。

2015年5月,王靖携信威集团通过全资子公司卢森堡空天通信公司实施“尼星一号”项目,面向海外进行卫星运营。2016年,王靖又在尼加拉瓜启动了“尼星一号”项目,拟投资建设尼加拉瓜通信卫星系统并开展商业运营,并借机拓展以拉丁美洲为主、覆盖美洲地区的卫星通信市场。项目原计划2019年4月发射,当年二季度开始运营,2023年达产。不过后来信威集团更改了计划,将发射时间推迟到2022年。2016年8月,信威披露拟以2.85亿美元收购以色列通信卫星运营商SCC100%的股份,将这家上市公司私有化。不过这一收购事项,因几天后马斯克SpaceX 公司的猎鹰 9 号火箭发生爆炸导致 SCC 的Amos-6 卫星全损而“泡汤”了。

王靖抛出“空天信息网络”战略:3年内,发射“一箭四星”,到2019年,要发射32颗或更多卫星,而他的终极规划是,要让信威集团运营的卫星将覆盖全世界95%的人口分布区域,成为为数不多的、几乎覆盖全球的卫星运营商。

不过后来有人爆料,信威声称注册资本达70亿的天骄航空厂房一直处于烂尾状态。

投资400亿美元挖尼加拉瓜运河

2012年8月,他在香港注册成立香港尼加拉瓜运河开发投资公司(HKND),扬言要投资3300亿人民币开挖尼加拉瓜大运河。此前王靖通过当地电信投资,认识了尼加拉瓜总统丹尼尔·奥尔特加。

2013年6月14日,王靖与尼加拉瓜总统丹尼尔.奥尔特加签署《尼加拉瓜运河发展项目商业协议》,运河项目投资额高达400亿美元(约合2450亿元人民币),HKND集团拥有独家规划、设计、建设,以及在一百年内运营并管理尼加拉瓜运河和其他潜在项目的权利。根据协议,王靖的私人公司香港尼加拉瓜运河开发投资有限公司将在尼加拉瓜开挖一条全长276公里的跨海运河,连通太平洋和大西洋,并开建两个深水港口,一条输油管道,一个世界级自由贸易区,一个机场。随后,尼加拉瓜国民议会正式批准该商业协议。

消息一出,震惊世界。南美洲航运主要依赖巴拿马运河,巴拿马运河通航能力严重不足,尼加拉瓜运河将极大提升南美洲的航运吞吐量。但开挖尼加拉瓜运河并不是一件容易的事。王靖在发布会上说,此项目一旦完工,将直接挑战500英里外巴拿马运河的国际地位,改变当时的国际航运格局;信威集团将会获得全球8%的物流定价权,是个持续盈利的大项目。王靖在国内被券商称之为“人中龙凤”。

2014年,王靖宣布工程开工,项目在五年后完工。

王靖曾称尼加拉瓜运河项目参与人员多达千人,“公司在尼加拉瓜,单单是科技人员就有500多人,在中国国内还有600多人”。后来的调查却发现:所谓的运河项目,当时对外宣扬的海内外的员工数量达到了上千人,但其团队数量还不到30人,并且整个运河工程只修了一条11公里的石路。就连这条砂石路也出了问题,欠尼加拉瓜运河项目服务公司200,000美元的工程资金,折算成人民币约130万元。因为欠薪,工人们罢了工,逼得尼加拉瓜领导人的儿子跑到信威北京的总部讨债。外交部出来辟谣:“该项目与中国政府无关,是民营企业自主行为”。

运河没动工,但信威集团在资本市场备受追捧。2014年9月10日,北京信威集团借壳“中创信测”登陆A股市场,12个交易日连续涨停,股价从8.45元一度涨至47.21元,累计涨幅高达458.70%,市值达到2000多亿元,成为A股市值最高的民营科技企业。持股31.66%的王靖身家超过600多亿元,成为位列全球前200名的超级富豪,比2010年入股北京信威时暴增300多倍,被资本市场誉为“运河狂人”。

王靖因此入选英国《金融时报》“25位最值得关注的中国人”,比肩雷军、马化腾,在2015年的胡润富豪榜上,与贾跃亭以395亿身家并列第7名。

由此,信威看似走上了快车道,高潮一个接一个,好消息应接不暇,股民们也疯狂追捧,信威的股价持续高升。2015年,信威集团市值突破2000亿。王靖的身价水涨船高,估值高达500亿元,而当时阿里巴巴的马云身价也才286亿元。

航空发动机与深水港

2013年12月,王靖还宣布在乌克兰投资“克里米亚海港”项目,计划一期投入30亿美元,二期投资不低于70亿美元。但仅隔了一年,由于地方局势原因,王靖暂停了深水港项目。王靖宣称:“克里米亚深水港建成后,年吞吐量将超过1.5亿吨,直接缩短中国到北欧的运输距离近6000公里,极大地促进中国与亚欧国家的商贸往来。”不过,很快乌克兰政府换届,新总统波罗申科上任,就否决了该项目。

又比如,2015年,他成立中国海外安保集团公司(空壳)。

再比如,2014年,成了北京信威集团老板后,王靖陆续成立4家“天骄”系投资平台(空壳):北京天骄航空产业投资有限公司、北京天骄影视产业投资有限公司、北京天骄建设产业投资有限公司、北京天骄体育产业投资有限公司。

王靖还计划引进乌克兰航空发动机,让中国航空技术进步10年,2014年10月,王靖在北京成立了天骄航空产业投资有限公司。此后,天骄航空与马达西奇建立了全面战略合作关系,双方计划在我国国内合作建设航空发动机生产基地。

乌克兰的马达西奇公司是世界知名的发动机生产商,主要为固定翼飞机和直升机提供动力系统,在苏联时期,有“苏联航空工业的心脏”之称。苏联(俄罗斯)赫赫有名的安-124、安-225、米-17、米-26、卡-27等飞机都使用它的发动机。苏联解体后,厂长博古拉耶夫将公司收为己有并运作上市。2014年,乌克兰与俄罗斯的关系陷入冰点,政府禁止本国企业向俄罗斯出口军用设备,这导致长期依赖俄罗斯市场的马达西奇公司陷入订单大批被中止,即将破产的境地。博古拉耶夫于是有意将公司出售。航空发动机版块是优质资源,而且这次的性价比比较高,自然就引来不少买家围观。王靖是最终的赢家。

一方面,北京天骄航空产业投资有限公司借款1亿美元给马达西奇公司补充流动性。王靖通过掌控在巴拿马、塞浦路斯、维京群岛等地的7家离岸公司,悄悄收购博古斯拉耶夫家族手中的马达西奇公司股份,连同在二级市场上隐蔽吸收,最终他持股56%马达西奇公司。

另一方面,马达西奇公司协助北京天骄在重庆建厂(重庆马达西奇天骄航空动力有限公司),生产和维修马达西奇产的发动机。这个项目得到重庆市政府的大力支持,被寄予了牵引地方航空产业链发展的厚望,成为战略性新兴产业培育的重点项目。

2015年底,在重庆渝北区的天骄航空动力产业基地项目正式签约,乌克兰第一副总理、乌克兰驻华大使、马达西奇公司总裁等均到场。该基地由乌克兰航发巨头马达西奇提供全套技术方案,规划总投资额200亿元人民币,一期项目建成后,2020年产值就有望达到500亿元。

王靖计划把北京天骄旗下的马达西奇注入信威(借壳上市),因国内的铺垫己经完成,目标指日可待。

2017年,王靖向乌克兰证券监管机构(乌克兰反垄断委员会)申请将全部股份(之前通过不同公司购买)归集到北京天骄。如果如愿,回国借壳稳成。由于飞机发动机属于战略技术产品,7月,乌克兰国家安全局以涉嫌“破坏活动”的名义,开始介入马达西奇并购案,对双方合作展开调查。

2018年3月,乌克兰最高国安会议做出决议,要将马达西奇公司国有化,乌克兰法院冻结了王靖公司的股份。2019年,新总统泽连斯基上台,直接否决了这项收购案。

在乌克兰那边,2021年3月,总统泽连斯基签署命令将马克西奇公司国有化,即是政府没收马达西奇公司100%的股份,同时,制裁北京天骄公司及其公司控制人王靖:冻结资产、限制交易、禁止进入乌克兰领土等。王靖通过国际仲裁索赔,许多人认为,这只不过是他做做样子而己。

在重庆,注册资本达70亿元的天骄航空产业园早己处于烂尾状态。

但王靖将停牌两年半的信威集团复牌,且伴随的是一条“重磅消息”:信威集团将与北京天骄航空产业有限公司重组,引进乌克兰马达西奇发动机技术,解决中国的飞机发动机难题。

这次投资者美元不买帐,硬着头皮复牌的信威集团迎来连续43个跌停。2020年4月20日,信威集团再次停牌。2021年5月,上交所决定终止信威股票上市,6月1日,被正式摘牌。王靖被上交所公开谴责,要求他10年内不得担任上市公司的董事、监事和高管。2022年2月23日,信威集团被北京近岭资本管理有限公司申请破产清算,法院方正式开始着手选任破产清算管理人的工作。

信威集团玩完了,输家是超过15万的股民,以及中了王靖套路的那些金融、投资机构。

王靖早已将持有的信威股票全部减持或质押,套现超过百亿元人民币。

早在2016年,企业正风光无限的时候,王的老底被人查了个底朝天。此后不到6年时间,信威巨亏268亿,暴雷退市,社保基金都被拉下水,为其提供贷款的国开行280亿资金打了水漂,15万股东人均爆亏24万,总部大楼被拍卖,最终无人问津流拍……

2015年9月以后,信威集团借壳上市和定向增发的巨额限售股陆续到期解禁,相关的股东套现。2015年,一位名叫“杨全玉”的七旬股民出售信威股票套现41亿元,迅速引起媒体关注。

当年12月,有媒体刊出长篇报道《信威集团隐匿巨额债务,神秘人套现离场》,迅速把王靖与他的骗局推向了大众的视野。除了指出信威集团债台高筑、财务造假,报道还提到,像“杨全玉”这样的神秘套现人足足有37位。重磅“报料”一出,信威股价应声跌停,次日,信威集团宣布停牌。

(自此之后,信威集团陷入连年的巨额亏损,自2017年-2020年4年的时间里,信威集团的对应亏损金额分别为17.54亿元、28.98亿元、184.36亿元、33.84亿元。)

2016年2月,信威集团宣布资产重组。

王靖开始谋划新业务、新故事装入上市公司,试图拉升股价。他“扯”起几面“大旗”:1. 宣布收购以色列商业航天公司太空通信集团,号称为“一带一路”提供通信保障服务;2. 投入10亿元资金购买大型通信卫星“尼星一号”(尼加拉瓜通信卫星一号),从地面通信设备供应商“一步登天”,转型“空天信息网络”服务商;3. 与湖北省产业投资平台合作,联合打造航空及舰船动力科技园区,争取两机专项(“发动机和燃气轮机重大专项”)国家资源扶持。

这几个“大动作”(最终是不了了之)没能“吹”出效果,2016年5月复牌后,股价没能提升,2016年12月,公司再次停牌。

2021年,上交所发文谴责王靖,称其在十年内不适合就任上市公司高级管理职位。

王靖虽然身败名裂,但他早已套现离场,不知所踪。

把报效国家做成生意

王靖在画饼方面炒的是国家战略,企业的发展理念更是简单粗暴——“报效国家”。

王靖入主信威之后,不仅在信威集团办公大楼前立下“报效国家”的巨幅石碑,更做成巨幅字幕挂在大厅,公司办公室里、会议厅内随处可见爱国语录。甚至公司的广播也是上午播放国歌,下午播放《打靶归来》。

政府鼓励让民营企业进入空间领域,王靖就放卫星;政府说中国企业要走出去,王靖就去挖尼加拉瓜大运河;政府打造5G技术,王靖就进入5G通信领域。

王靖的这些行为,让人对他的背景揣测纷纷,甚至有国外的媒体把王靖称之为“帮助大国崛起的神秘大拿”。王靖不仅把爱国故事讲得天花乱坠,而且连尼加拉瓜的领导人也被忽悠成了他表演的陪练。

只是当王靖画的“大饼”消失后,大家才缓过神来。用“爱国”作为一种手段来推动股价,王靖可以说是商界第一人。

卢恩光:五假干部

年龄造假

卢恩光出生在山东阳谷县,什么时候出生的,除了他没人能说清楚,因为他的年龄存在造假情况。

履历表上填写的出生年龄是1965年,而认识他的人则说他的实际出生年龄是1957年,竟然少填写了8岁。

为什么这样?为了当教师。

卢恩光是1984年才通过不正当手段当上民办教师的,据卢恩光小时候相交的两位人士说,卢恩光是初中毕业,但是学习成绩一般。除了语文成绩尚可,英语、数学和物理考试没有及格过,数学成绩还总是年级倒数,没有考过高分。

这样一个标准的“差生”,是如何进入学校教书的,已经不得而知,一个流传很广的说法是,他靠两瓶罐头贿赂村支书,当了民办教师。

为了能当上教师,他将自己的学历填写为高中。

实际上他到了上高中的年龄,当地还根本没有高中,于是他将年龄推迟了8岁,弄到了一张高中毕业证,如愿以偿当了教师。

语文成绩相对较好的卢恩光,偏偏被安排到小学五年级担任数学教师,这可让他出了不少洋相。

他的学生们回忆说,当学生们问卢恩光数学题的时候,他的口头禅有两句:“自己钻研”、“你问我,我问谁?”

名字造假

卢恩光不仅年龄造假,名字也造假。

名字造假又是为了什么?跟过去切割。

在当民办教师之前,卢恩光只是个街头混混、地痞流氓。他的家乡阳谷是水浒英雄武松打虎之地,因此早年的卢恩光崇尚暴力,到处拜师学艺,学得一身好武艺。

俗话说,艺高人胆大,武艺在身的卢恩光在家里开始招收徒弟,传授武艺,身边有了一批追随者。

之后,他有了底气,整天带着一帮弟兄在大街上打打杀杀。

久而久之,卢恩光就打出了名气,他的名字在阳谷无人不知,无人不晓。因为卢恩光在家里排行老三,发迹后被道上的人唤作“三哥”。

他的真实年龄,则是通过他当年的小兄弟推断出来的。

一位喊卢恩光“三哥”的拜把子兄弟,是出生于1958年1月,说明他至少是1957年出生。而曾经的“三哥”到了学校之后,他社会上的兄弟经常去学校找他,在办公室抽烟喝酒,搞得学校里是乌烟瘴气。

因此,当时村里人没有几个能瞧得起他的,认为他这辈子就那样了,不会有什么出息。谁知道,卢恩光一不小心竟然成功了。

上世纪90年代,社会上兴起校办企业之风,让卢恩光看到契机。

1990年,默默无闻的卢恩光找到高庙王中学和当地教育局、财政局领导,吹嘘自己有经商才能,还发明了快速绘图仪,能在一年内创收千百万。

卢恩光凭着三寸不烂之舌,说动了各位领导,得到了县财政局下拨的20万元贷款,创办了一家校办企业。

这家企业名为校办企业,其实就是卢恩光的家族企业,从厂长、会计,到出纳、保管,甚至车间主任和门岗,都是他的亲信和当年道上的小兄弟。

最后,卢恩光这个方丈肥了,20万资金打了水漂,厂子也倒闭了。

尽管赔得一塌糊涂,但是卢恩光却就此洗白,成为企业家。1994年,阳谷县科仪厂厂长卢恩光被评为山东省十大杰出青年。

在参加杰出青年评选的时候,卢恩光心说自己不能用自己原来的名字卢方全了,那是自己在道上混的时候用的名字,面子上并不好看。现在自己已经走上正道,当然要与过去切割,避免人们起底他不光彩的历史。

因此,用了几十年的名字卢方全被弃用,他开始以卢恩光的名字走入新生。从此,江湖上不再有卢方全,政坛新星卢恩光冉冉升起。

不过要说卢恩光发达全靠造假,也不符合事实。

比如1997年,卢恩光成立山东阳谷玻璃工艺制品厂后,赚得第一桶金,靠的是掌握了诺亚口杯(即双层玻璃杯)的专利,产品在市场上畅销。

双层玻璃杯就是我们现在生活中常见的真空杯,它注入开水之后,既可以保温,杯口还不烫嘴,手捧杯体的时候不也烫手,这种产品很快风靡全国,让卢恩光赚足了钱。

不过他的钱来路是否干净,也有争议。

吉林农民董玉杰,就指控卢恩光剽窃了自己的专利。他说自己在1993年,就申请了“双壁式口杯”专利,专利到1997年4月失效。但是他发现,卢恩光的企业一直在使用这项技术,牟取不义之财。

他随即找到卢恩光,要求对方支付专利费100万元。卢恩光假意答应,背地里报警,董玉杰锒铛入狱,阳谷警方以敲诈勒索罪,判处其有期徒刑四年。

由此可见,卢恩光在整人方面,还是有些“真本事”的。

古人说,为商者一本百利,为官者一本万利。卢恩光深谙此理,在生意如日中天的时候,果断向官场过渡,当了乡党委书记,阳谷县政协副主席、党组成员。

卢恩光是什么时候成为党员的?这又引出他的一项造假历史——

入党资料造假

卢恩光知道,要想步入政坛,不是党员可不行。但按照程序入党太慢,需要一到两年时间;他觉得太慢了,要只争朝夕。这样的话党龄长,升迁快。

怎样才能突击入党?只能造假。

于是他找到时任高庙王乡党委书记的李恒军,将5000元入党介绍费装在玻璃杯里,放到了办公桌上。李恒军见钱眼开、心领神会。

为了让卢恩光早日入党,他们合伙造假,将《入党申请书》申请书的时间往前提了两年。可是卢恩光造假心切,还是穿帮了,他未卜先知,在1990年的《入党申请书》中 ,就写到了在“南巡精神鼓舞下”云云。众所周知,小平同志是在1992年南巡的,你卢恩光两年前就得知了这个“内幕”,真是滑稽之极。

由于卢恩光打点到位,开会讨论的时候一致通过。就此,卢恩光如愿以偿入党,仕途平步青云。

履历文凭造假

入党之后,卢恩光并没有忘乎所以,他明白这只是万里长征,才走了第一步。要想升迁,自己的“高中学历”和民办教师经历,以及开工厂的经历,都是搁不到桌面上的,要继续造假。

同样用金钱开道,他轻松地制造了假的档案,假的履历,为自己升迁铺平道路。

凭着自己的高学历和辉煌履历,他开始进入政坛快车道。1999年5月,山东省政协因人设岗,增设鲁协科技开发服务中心。卢恩光得到消息后,立即带着资金前去“运作”,最后如愿成为中心副主任。

一年多后,卢恩光又用同样的手段,赢得了领导的重视,担任了中心主任,成了正处级干部。

反正卢恩光仍然控制着自己的企业,挂着科技开发服务中心的牌子做生意更加方便,税收方面一年少交千八百万不是问题,拿这笔钱来打通关节已经绰绰有余,这样的“买卖”实在是太划算了。

由于卢恩光财大气粗,能为机关干部发福利创收,完成各项任务,所以大家都对他毕恭毕敬,即使他一年到头不去开发服务中心上班,大家也不管。

其实,卢恩光造假的手段并不高明,甚至连学历都舍不得让办假证的人去制作,而是自己随便填写,用假公章盖上,一眼就能看穿。

而且卢恩光的任免文件、工资表等重要内容缺失,牛唇不对马嘴。

但是因为他打点到了党组会,组织、人事部门也就不好意思提出质疑,就抱着走过场的心态。他们不仅不认真把关,甚至即使从中发现问题,也没有人敢去深究。

卢恩光从一个街头混混、民办教师逆袭成为处级干部,按理说应该知足了。但是卢恩光有远大志向,根本不满足于现状,他的目标是到北京去做官,好光宗耀祖,让本族人引以为荣。

2001年,他从自己的企业中拿出500万元,以其他企业的名义捐助给报社,谎称是自己拉来的捐款,因此在华夏时报社买到一个职务,一跃成为副局级。

2003年,卢恩光他再次拉来了1000万所谓“赞助”,顺利晋升为正局级。

这天晚上,他高兴得睡不着觉,早知道可以花钱买,何必原地等待这么多年。

从1997年到2003年,卢恩光仕途最顺利的时期,他像坐火箭一样,一年一升迁,六年提六级,从乡镇一直到京城,从副科级到正局级,让人叹为观止。

到了京城,成了正局级,卢恩光该满足了吧,其实不然。他认为自己级别虽高,但是报社不是党政机关,有点低人一等的感觉。只有调入政法、组织、纪检等系统,才能挺直腰杆,扬眉吐气。为了这一战略目标,他像管理企业一样,给自己制定了三个“狠抓”、两个“满意”的工作计划。

三个“狠抓”,就是狠抓工作,狠抓领导,狠抓群众。

两个“满意”,就是让领导满意,让群众满意。

说白了,就是让大家得到的利益最大化,给他点赞,为自己的升迁赢得资本。

功夫不负有心人,2009年05月,喜讯再次传来,卢恩光终于好梦成真,被调到司法部,担任司法部政治部副主任、兼人事警务局局长;2015年11月,卢恩光更上一层楼,担任了司法部政治部主任、党组成员,达到了人生巅峰。

从乡干部,到部级干部,卢恩光只用了短短18年的时间,升迁速度之快,让人瞠目结舌。

然而,人们只羡慕卢恩光的成功,而忽略了他的“艰辛”。卢恩光每升迁一步,都是用大量金钱开道。为了到司法部工作,卢恩光的付出更多,不只是金钱,还有精力。

为了给领导一个好印象,年近花甲的他,每周都到领导家里去。送肉菜水果,送土特产品,耗资虽不多,精力却都搭上了。

即便是对自己的父母,卢恩光也没有如此孝顺过。

更让人感慨的是,卢恩光一大把年纪了,像个忠诚的仆人一样,将领导家里的家务活全承包了。什么书架坏了,玻璃破了,花盆小了,下水道不通了,他全管。

回想一下,卢恩光真不容易。他甚至不敢让自己的孩子叫他爸爸,而是叫“姨夫”。

之所以如此,是因为他还涉及一个造假行为。

家庭情况造假

卢恩光共有七名子女,但只敢填报了两名,因为他怕自己因违反计生政策,影响自己升迁。

其他五名子女,这些年的户口都跟他不在一起,当然也就不能和他生活在一起,而是通过假手续落户在亲戚家。

为了不穿帮,到了家里,那5个孩子都不能叫他爸爸,而是叫姨父、姑父。

用卢恩光的话说,就像干地下工作那样。

“吃得苦中苦,方做人上人”,卢恩光经过千辛万苦,终于达到了人生的光辉顶点。

但是,他过得舒心吗?答案是否定的。

他自己坦诚,过得提心吊胆。

尤其是成为副部级之后,他活得更累。

因为这一来,自己是中管干部,成为中央巡视组、中央纪委重点监督的对象。而自己是一路造假过来的,不是靠真才实学和政绩是靠买或靠送得来的官位。

一切就像建造在沙滩上的楼阁,一有风吹草动,就会倒塌。

果然,2016年12月中旬,卢恩光突然落马。

可悲的是,有的官员升迁是为了受贿,而卢恩光仅仅是为了一个虚名而不停行贿,在他的政治生涯中,并没有贪污的记录。

这些年,他为了当官,行贿出去1278万元。

最后,乌纱帽被摘,还锒铛入狱,获刑12年,处罚金人民币300万元。看似精明过人、很有生意头脑的的卢恩光,却做了人生一笔最亏本的“买卖”。

黄德坤:从杀人犯到

1998年10月17日深夜,凯里某派出所副所长安坤正准备到出租房休息。只是安坤不知道,自己一个副所长早就被人盯上了。

当安坤一个人走在无人的拐角处时,两个黑影突然冲了出来。两人动作迅速,一个人用钝器击打安坤头部,一个人对着安坤连刺两刀。很快安坤就没了气息。其实整个过程都没超过两分钟。

这两个人的目的不仅是安坤,还有他腰间那把六四式手枪和一匣子子弹。得手之后,两人就无影无踪了。

第二天一大早,安坤的尸体被路过的同事发现,而安坤早就没了性命。手段如此恶劣的行径,很快引起了警方注意,只是,警方没想到,破案足足等了18年。

另类小伙黄德坤

其实,安坤之所以被害,跟发小黄德坤分不开关系。

黄德坤是贵州凯里市人,黄家一共有五个孩子,排行老四的黄德坤,从小就是一个异类。跟整个家庭都格格不入。

黄家是标准的根正苗红,黄德坤的四个兄弟姐妹全都在公安系统工作。因此,黄德坤从小,也被父亲寄予厚望。只是黄德坤志不在此,满心满眼都是武侠梦。

当时的黄德坤,不仅不喜欢学习,每天都梦想着自己做一个逍遥快活的武林高手。因此,黄德坤还跟着武功师傅学习过一段时间,而且力气特别的大。

所以,黄德坤在外行走的时候,经常一言不合就动手,向来奉行的就是拳头说话。只是,黄德坤不好好学习,稍有不顺就动手,根本没有工作单位愿意收。

看着儿子的不靠谱,父母非常的着急。于是就托关系把黄德坤送进了凯里运输公司上班。当时,二老想着给国企工作,最起码是个铁饭碗,饿不着。

只是,黄德坤根本不明白二老的一片苦心,反而干了几年之后就不耐烦了,直接瞒着父母辞职做买卖了。

可是黄德坤根本不是经商的料,最开始的时候,黄德坤开了一家录像厅,专门给小年轻播放影片赚钱,后来,黄德坤开了一家歌舞厅。一段时间之后,歌舞厅经营得有声有色,可是歌舞厅有个弊端,那就是环境相对闭塞,最容易造成火灾。

1996年,就在黄德坤歌舞厅开始盈利的时候,一起火灾烧光了黄德坤所有积蓄。无奈之下,黄德坤只好转让给别人,收回本干别的营生。

没多久,黄德坤开了一家冰淇淋加工厂。可是冰淇淋本来就是季节性食品,而且竞争压力非常的大。因此没多久,黄德坤的加工厂就宣告倒闭了。

经商失败起贪念

因为两次经商失败,黄德坤背负巨债,心情烦闷的黄德坤,叫了自己的发小潘凯平出去喝酒。两人是一个在大院长大的发小,而且还曾一起到凯里货运公司上班。

而且,潘凯平母亲早逝,父亲另娶了一个后妈,当时的潘凯平日子很不好过,在家里被后妈欺负,在学校被同学欺负,每次被欺负的时候,黄德坤都会出手帮忙。所以,打小潘凯平就被默认成了黄德坤的小弟,而跟黄德坤一起长大的,还有安坤。只不过,后来安坤进入了公安系统,三个人的人生轨迹发生了变化。

听到黄德坤叫自己喝酒,潘凯平想也没想就答应了。两人一边喝酒,一边互相吐露自己的不如意。说着说着就说道了安坤。安坤当时是副所长,每天坐办公室,出门腰里挎着枪,看着就神气。

本来是羡慕,而是由于酒精的作用,黄德坤对安坤腰里别着的枪起了兴致。还产生了一个念头,如果自己有一把枪,然后抢劫银行还债,就再也不用天天躲债了。

可是酒醒之后,黄德坤觉得自己很荒谬,早就禁枪了,自己到哪儿去搞一把枪呢?但是,债台高筑的他,已经没有了退路。

于是,黄德坤再次找到了潘凯平,对他说:我有一个办法来钱快。潘凯平本身就活得不容易,听到发小这个提议,想也没想就同意了。

周密的夺枪计划

当黄德坤说出,自己想要夺走安坤的手枪,然后抢银行的时候,潘凯平犹豫了一下,但是苦日子早就过够的潘凯平,还是同意了跟黄德坤合伙。

可是两人都知道,想要对付一个身手了得,而且警惕心很高的派出所副所长,可不是一件轻松的事情。于是,黄德坤特意买了一把匕首,找了个废弃仓库开始计划。

黄德坤每天跟踪安坤一家的作息规律,一段时候,黄德坤就发现,安坤最近经常不回家,有时候半夜下班后,就会独自跑到租住的房子里休息。

于是,就在1998年10月17日这天,安坤照旧到出租房休息,可是走到半路的时候,就被两个人伏击,一个人猛击安坤头部,一个人对安坤身体连刺两刀。最终了解了安坤的生命,夺走了安坤的配枪。

银行行长灭门案

就在安坤殉职之后,警方集中警力准备把这伙猖狂的匪徒逮捕。可是由于侦破手段比较落后,一直没有什么线索。

谁知就在警方焦头烂额的时候,仅仅时隔44天,凯里又发生了一件特殊的火灾。被害人是当地某银行行长乐贵建一家三口和一位邻居。

当时乐贵建家发生了一起火灾,可是蹊跷的是,火灾现场发现了安坤手枪子弹的弹壳,很显然两起命案是同一伙人所为。

只是,这个案子跟安坤案一样,一直没能侦破,而且一等就是十多年。

被指纹泄露的天机

2016年,凯里澎湖改造办副主任黄德坤,因为严重违纪被纪检委请去调查。

就在凯里市发生两起重大命案的同时,黄德坤的命运开始步入正轨,黄德坤成为了开发区一把手杨某的专职司机。

由于黄德坤身手了得,而且办事细致认真。从来不会在领导面前乱说话,所以黄德坤给杨某留下了极其深刻的印象。

2006年,杨某离任,黄德坤被推荐去给洪金洲开车。而洪金洲也很看好黄德全,一段时间相处之后,就萌生了提拔黄德坤的想法。

很快,黄德坤就拖累了司机岗位,成了开发区内部职员。从此之后,洪金洲在局里发号施令,而黄德坤就是他手下最得力的实施人。

2007年,黄德坤由于能力出众,被调任到城管局工作,专管拆迁协调工作。由于黄德坤学习过功夫,在黄德坤的努力之下,拆迁工作异常顺利。

很快,黄德坤就等来了升职的机会,成为了开发区城管局局长。之后,又被调任为棚改办公室副主任。只是升官之后的黄德坤,很快就露出了真面目。

深知拆迁容易捞油水,于是,黄德坤开始将手伸到拆迁里,很快就靠赚差价捞了不少好处费。

有了钱之后,黄德坤开始嫌弃妻子不争气,不满妻子只给自己生下一个女儿,想要有儿子养老的黄德坤,在外包养情妇,还偷偷生下一个私生子。

只是,黄德坤并没有嚣张太久,很快就被监察部门盯上了。

由于证据确凿,黄德坤对于自己的违纪行为供认不讳,就在签字画押的时候,指纹识别系统却发生了“异响”。

闻讯赶来的民警发现,黄德坤的指纹出现异常。发现,黄德坤的指纹居然跟十八年前的旧案指纹一模一样。于是,对黄德坤进行了审查。

根据黄德坤提供的信息,警方赶往清水河打捞弃枪。看着锈迹斑斑的枪体,一串编号证实了这把枪,就是当初安坤的配枪,也是行长灭门案的重要凶器。

还原惨状

十八年前,警察被害案和银行行长灭门案的凶犯正是黄德坤。而轰动一时的凯里双案,终于有了进展。

根据黄德坤交代,当时之所以对付安坤被,就是想要夺枪抢劫。

等枪到手之后,黄德坤和潘凯平就准备去抢劫银行,由于安坤被杀而且配枪丢失,所有银行金铺都加强了戒严。

看到抢劫银行毫无胜算之后,黄德坤注意到了银行行长乐贵建。作为行长,乐贵建家里肯定不缺钱,既然银行去不得,一个乐贵建还是很容易搞定的。于是给潘凯平商量,去抢劫乐贵建的家。

于是,黄德坤就开始去乐贵建家里踩点。由于黄德坤的妻子,曾经在乐贵建手底下工作过。所以,黄德坤灵机一动,拎着一点礼物就敲开了乐贵建家的大门,装作访客的样子大摇大摆地走了进去。

只是,百密一疏,黄德坤忘记关防盗门了。就在黄德坤和潘凯平行凶的时候,由于发生了巨大的声响,导致楼下邻居意外夫妻二人在家里打孩子。

邻居刘某跟乐家关系极好,听到孩子的哭声,就冲了上来,想要劝一下夫妻二人。冲动之下进入屋里后,发现客厅居然有两个陌生人。察觉不对劲的刘某,赶紧往门外跑去。

情急之下,黄德坤对着刘某就是一枪,然后潘凯平拿着匕首连续刺了几刀。

乐贵建看到两人手段如此凶残,再跟黄德坤搏斗的时候,逃到了主卧室。看着乐贵建反抗的太激烈,担心事情发生变故,黄德坤直接朝着乐贵建开了两枪,最后乐贵建头部中枪倒地。

剩下乐贵建的妻女,很快就被解决了。

最后四个人全部遇害,而乐贵建一家所有的现金和贵重物品,被黄德坤两人全部搜走。为了毁尸灭迹,黄德坤临走之前打开了两瓶白酒,打开了煤气罐阀门,然后点上火就逃走了。

只是,黄德坤没发现,其实煤气罐根本没有多少气儿。虽然点了火,但是并没有引起火灾,所幸,帮警方保住了不少证据。其中就有黄德坤留下的指纹。小结

黄德坤以为自己做得天衣无缝,还错开时间处理了作案枪支。结果,还是被一组指纹暴露了行踪。

也许,多年前的侦破手段不高,指纹采集并没有完善,但是完善指纹库是迟早的事情。黄德坤最终还是被逮捕归案了。

2018年,在逃18年的黄德坤潘凯平,最终还是在法庭上认罪了,当年惨绝人寰的凯里双案,终于告一段落。等待两人的,则是法律的惩罚。1984年,王洪成发明“水变油”

自1984年初开始,哈尔滨的公交车司机王洪成正式推出他的“发明”,他在各地进行所谓的“实验展览”,向政府部门与公众介绍“水变油”的发明。当时还引起中央领导的注意,还亲赴哈尔滨去看望王洪成,后来王洪成得到数以亿计的“科研投资”。

当年王洪成的发明引起科学家很大的轰动,如果真的能让普通的水变成油,将会为国家节省一笔巨大的能源投资,他的发明还被认为是“中国第五大发明”。1995年,全国有41位科技界的政协委员联名呼吁调查“水变油”的情况,一场惊天骗局的真相逐渐浮出水面。

根据调查统计报告,王洪成发明“水变油”的骗局,直接经济损失达4亿人民币之多,对社会造成了非常恶劣的影响。67路公交车

王洪成,1954年8月出生在黑龙江哈尔滨,由于家庭条件比较差,他只上过4年学,连小学文凭都没有拿到。辍学后,王洪成在人民公社养过猪,学过一段时间的木匠,后来还参军入伍。

在部队期间,王洪成拿到了汽车驾驶证,从部队退伍后直接在哈尔滨公共汽车公司当司机。日复一日的工作让王洪成觉得非常无趣,他希望自己能够出人头地,并且过上富裕的生活。当时改革开放的浪潮已经涌来,王洪成也在其中看到发展的机遇,希望能够赶上这波发展的浪潮,于是开始琢磨怎样才能赚钱。

通过某些关系,王洪成还在学校换了一张初中的文凭证书,这样能够在公司发展得更快。王洪成虽然没有什么文化,但他对科学研究有着非常高的兴趣,尽管自己没有过硬的知识作为研究基础,但他的想法还是挺新奇的。比如在书本中看到的“永动机”,在王洪成看来是可行的,他把一切发明的可行性都通过自己脑海中的理论来验证。

在公共汽车公司工作多年,王洪成突然觉得汽车每次都要加油,这是一笔非常大的开支,能不能用别的东西来替代它呢?当时全国都在提倡大力发展科学技术,在科学的基础上发展,很多科技产品都相继问世。在这样的大背景下,王洪成也是脑洞大开,他决定开始研究替代汽车燃油的材料。

为了达到成本最低化,王洪成查找了很多化学类的书籍,但只有小学文化程度的他,根本看不懂书本的内容。为了搞懂很多知识,王洪成还特意请教很多老师,但他学到的知识也仅是一点皮毛。想要研究燃油的替代材料,学一点化学知识是没有用的。既然走正道没有用,王洪成便开始想歪门邪道。一次偶然机会,王洪成在街头看到表演魔术和杂技的团队,他突然来了灵感,为何不将魔术和杂技的元素融入“研究”呢?

上世纪80年代,人们的普遍文化水平还非常低,大部分人根本没有上过学,对于很多物理、化学现象的认识程度不足。王洪成正好看到这一点,于是开始油的替代品的研究计划。为了节约成本,王洪成直接用水来进行“转化。他最先在水中滴入几滴油,然后点火,发现油能够正常燃烧,这让他有了一个新的想法。

既然通过技术手段无法研制出油的替代品,那干脆来个掩耳盗铃,通过水和油的混合物来骗人。为了保证“实验”万无一失,王洪成还用手段将眼前的水完全调换成油,在展示实验前可以让观众品尝容器中的水,当观众确定是水后,他再用手法将水给调换,最后再向水里随便滴几滴液体,便说这是“水变油”的重大发明。

王洪成的这些手段只能骗一骗文化水平比较低的观众,肯定是骗不过专业人士的眼睛的。为了能让“实验”看起来更加科学,王洪成利用从书本中学到的一点知识,在水中投入电石粉末(碳化钙),二者产生反应后会形成乙炔(C2H2),然后直接点火就能燃烧起来,并且可以冒黑烟。汽油等在燃烧的过程中如果燃烧不充分,也会有比较相似的现象产生。

如果遇到比较难骗的人,王洪成将会采用更加高级一点的方法,他在水中放入四氢化铝锂,物体与水发生反应后会冒出氢气,还能有许多小气泡冒出,点燃后会发生微爆声,这种方法看着更加能让人信服,但不到特殊情况,王洪成基本上不会用这个方法。既然“水变油”的诀窍已经掌握,王洪成便开始展示自己的“科研成果”。

1984年3月,公交车司机王洪成向媒体宣布一项重大发明“水变油”,由于从未听说过这种科学产品,从而引起社会各界的关注。根据王洪成的介绍,在四分之三的水中加入四分之一的汽油,然后再加入自己多年的研究产品“洪成基液”,就能够变成为“水基燃料”,用明火一点即燃,热值还要比普通的汽油、柴油还高,更重要的是没有任何污染,成本也非常低。

王洪成的“科研产品”一经问世,引发了社会各界的广泛讨论,很多人觉得如果产品真的有效,将会节省下很多成本。对于大部分汽车公司而言,也能节约很多燃料费用。普通老百姓用燃油的,也将更加便宜。在相对浮躁的思想环境下,更多的人愿意相信这种产品是可行的。

为了让自己的“科研产品”更加具有权威性,王洪成竟然还开办了一家新能源公司,聘请了很多“权威专家”,其实都只是一些高中毕业或大学毕业的学生,并不是专业领域的权威。社会上对王洪成的质疑声也非常多,他于是准备先发制人,请人写了一篇题为《王洪成水基燃料是领先世界的常温核聚变创举》的文章。

文章中还说明:“本文试图用国际上最新的高科技研究成果,常温核聚变反应来解释’以水代油’的形成机理,希望有助于克服中国第五大发明——洪成燃料推广中认为的观念障碍。”

明确来说,王洪成让人写的科学论文完全是胡编滥造的,然而封面上竟然还写着指导教师南京某某大学化学系教授的名字。后来有人去采访这位教授,得知此事后怒不可遏地说:“这是个骗子!一天有人打电话给我,让我指导研究水变成油的问题,我从来不相信水能变成油,就严词拒绝了。”

王洪成的目的已经达到,并且民众也相信他的研究成果。为了达到宣传的目的,王洪成还不断通过登报的方式来宣传产品,人们更加不敢轻易否定,普通老百姓认为登报的事情真实性比较高,并且还有权威专家的验证,这更加确立了“水变油”的真实性。1984年,黑龙江省副省长与王洪成取得联系,希望能够对“水变油”研究的真实性进行检测,但王洪成以仍在继续研究为由拒绝了。

同年5月,中央有一位领导亲赴哈尔滨探望王洪成,还观看了实验流程,最终被王洪成的手段所蒙骗。王洪成以科学研究为名,让领导批给他60万科研费用,并且还配了一辆豪华皇冠车。既然有领导的认可,王洪成的研究产品自然就成为了“香饽饽”,一个部队企业还专门为此成立公司,300多家乡镇企业拿出上亿资金给他搞共同开发。

估计连王洪成本人也没有想到自己能够骗到上亿的资金,他自己甚至都开始觉得“水变油”是真的,并且真的把自己当成了科学家。

这一场“水变油”的闹剧持续了十多年。1993年,公安部和物资部都发出通告,有关单位立即停止宣传“水变油”事件。原物资部干部严谷梁还在报刊上刊登一篇题为《应该用事实澄清“水变油”真相了》。可并没有引起人们的重视,反而还被王洪成给告上法院,最终王洪成反而成为“受害者”,得到广大民众的同情。

1986年,王洪成前往中国科学院说要求鉴定,可但准备鉴定时,他又毁约不干。还在中科院专利管理处偷了一份盖有中国科学院公章的文件和印有中国科学院抬头的空白信笺。王洪成回到家中用剪贴和复印的办法伪造了一份中科院发布的《王洪成发明成果证明》的文件,并到各地骗取合作单位的信任,到处招摇撞骗。

王洪成有了中科院的“权威证明”,于是变得更加自信。当时哈尔滨工业大学还特意组织水变油的鉴定会,参加鉴定的有哈工大和吉林大学的博士生导师等一批专家,当他们看到王洪成手中的中科院证明材料时,于是更加倾向于相信王洪成的科研产品。哈工大的校长和党委书记还因此两次给中央领导写信,非常诚恳地说明水变油是可信的,还希望能够大力发展水变油产业。

善良的大学教授们碰到了骗子,而恰恰又忘记了自己所应该坚持的科学真理,最终被王洪成所利用。有了大学教授的“权威认证”,王洪成的路更加顺畅了,无论社会上有怎样的质疑声,他都有反驳的资本。

1993年6月,王洪成正式对外宣布哈尔滨67路公共汽车全部使用“洪成燃料”,很多人都开始说:“洪成时代开始了,这是走向造福社会的里程碑。”为了真的让汽车跑起来,王洪成将各种燃油进行掺杂,还在其中混入肥皂类的物质,搅拌成乳化液,看起来是非常“先进”的物质。这种油的确能够让汽车运作,但它不仅不省油,反而还会腐蚀发动机。

为了让广大民众相信,王洪成根本不在乎发动机坏不坏,只要能够用这种油然汽车在大街上跑起来就行。在鼓乐声中,十几辆灌上“洪成燃料”的公共汽车都行驶到了大街上,这件事情还被制作成录像带发布在社会上进行宣传。王洪成的确有点得意忘形了,在多年的赞美声中,他已经彻底迷失自我,竟然把自己的“水变油”发明当成真的了。

没出一个月,哈尔滨很多公交车的发动机全部损坏,人们这才意识到所谓的“水变油”根本不起作用,汽车公司一边让人修理汽车,一边向王洪成索要赔偿,但王洪成根本不理睬。宣传用的录像带仍然继续在社会上播放,骗取人们的投资。谎言骗得了人们一时,却骗不了一世。

1995年,中科院院士何祚庥、郭正谊等人在全国政协八届会议上,联名提交提案,呼吁调查“水变油”的投资及对经济建设的破坏后果。中科院、哈工大、吉林大学等都是此次事件的受害者,由于王洪成伪造鉴定证明,导致很多人受骗,直接造成上亿元的经济损失。科学界都开始联名声讨王洪成,他的这种行为是在给科学界抹黑,同时还动摇了民众对科学的信任。

事情发生后,王洪成被收容审查。1997年11月14日,哈尔滨中级法院认为,以虚夸发明并触犯刑律,最终以销售伪劣产品罪,判处王洪成有期徒刑10年。这一场“水变油”的闹剧终于结束,可民间仍然还有人相信水能够变成油,王洪成的这一场骗局影响颇深。

杨显惠作品集

定西孤儿院纪事(选载)

目录

父亲

独庄子

炕洞里的娃娃

黑石头

姐姐

华家岭

走进孤儿院

顶针

俞金有

黑眼睛

打倒“恶霸”

院长与家长

蔓蔓

尕丫头回家

在胡麻地浇水

算账

陈孝贤

老大难

为父报仇

寻找弟弟

梦魇

守望殷家沟

后记父亲

今天是我重返饮马农场的最后一天,明天就要去小宛农场。

我是1965年到河西走廊西端的小宛农场上山下乡的,在老四连当农工。那是1970年吧,我们的连长调至饮马农场的商店当主任,他把我也调过去了,在饮马农场的商店当售货员。

由于是最后一天的滞留,吃过晚饭之后,我特别地在场部走了又走,又一次看了知青回城之后,留下来的农工们第二次创业建立起来的啤酒花颗粒加工厂和麦芽厂。直到夜色四合,我才回到招待所。我刚推开招待所接待室的大门,有个人忽地从沙发上站起来了,喊了声梁会计。我知道他是在叫我,且口音有点熟悉,但一时间却没认出他来。我说,你是……

我是何至真呀。

啊,我想起来了,他是农场机耕队的机务员——开拖拉机的。我说,你怎么来了?他说,我来看看你呀,听说你来了。我很感动,拉着他上了楼进了我住宿的客房。沏好茶之后,我说,我当再也见不到你了,人们说你调到黄闸湾的变电所去了,离这儿十几里路呢。他说,我是听我们所长说你来了,赶来看看你。我真是很感动,我说,哎呀太……太……我连着说了几个太字,也没说出太什么来。这次来饮马农场,土地还是那么亲切,当年栽的白杨树苗都已经变成参天大树,但熟人没几个了:知青都回城了,老职工都退休了,走到哪儿都是生面孔,就是当年五大坪过来的一百名孤儿也只剩下二三十人了,还都散布在几十平方公里的十几个生产队里,很多人都没见上面。真有一种人去楼空的感觉。我亲热地问候他:还打篮球吗?他笑了:还打什么篮球呢,都退休了。我也笑了,我的问话太可笑了,那是三十年前的事了:农场每年都要从连队挑十几个大个子爱运动的人组成篮球队,集中训练几天之后去师部和其他农场的篮球队比赛,我和他就是在篮球队认识的。

我们聊起了篮球,聊起了朋友,家庭和儿女,我问他:这些年常回家吗?他回答:一次也没回过。

我很惊讶:怎么一次也没回过?

你知道的,我家没人了。

我点了点头:知道知道。沉默片刻,我又说,亲戚总是有几个嘛。

不来往。我不愿和他们来往。前几年有个叔叔写信来,说要来看看我,问我坐哪趟车怎么走,我没回信,撕掉了。

怎么呢?

我挨饿的时候,需要人帮助的时候,他们到哪里去了?

我静了一会儿说,至真,你一次也没认真跟我讲过你的家庭。

我跟谁也没讲过。那些伤心的事,我不愿讲,也没人愿意听。

谁不愿意听,是你不愿讲的。都老了,还想在心里埋一辈子,跟老朋友都不讲吗?

是老了……他叹息着说。这几年我的思想也有点变化,曾经想过把过去的事给孩子们讲一下,起码叫自己的后代们知道一下我受过的苦。我也给他们讲过,可他们不爱听。今天你要是想听,我就给你讲一下。

就从我父亲讲起吧。我们这些从河靖坪来的孤儿,父母都是死光了的。当然,一个人和一个人的死法不同。

我父亲1958年去了皋兰县当民工,大炼钢铁。那时候不是大跃进吗,要大炼钢铁。定西地区的多数县没铁矿,没煤,全地区的民工都集中到皋兰县和靖远县去炼钢。光是通渭县就去了一万七千民工。1959年春天,炼钢失败了,我父亲说过,就炼了些黑黑的焦炭疙瘩,就停止了,放回来了。放回来也不叫闲着,又派去修白(银)宝(积山)铁路,直到1959年夏季才又放回家来了……

不对不对,不是放回来的,是我母亲没了,我父亲跑回来了,他不放心我和我妹妹。我们家三个孩子,我最大,1947年生的,还有两个妹妹。

我母亲是这样没的:1959年春天公社食堂就没粮了,就天天喝糊糊,到夏季,食堂干脆就喝清汤。你可能觉得奇怪,夏季小麦下来了,怎么没粮吃了?都叫大队拉走交到公社去了,说是交征购呢。征购没交够,搜粮队搜社员家的陈粮。结果把农民家里藏下的一点陈粮搜走了,社员们就剥榆树皮充饥,挖草胡子,吃骆驼蓬。我母亲有一天在麦场干活,实在饿得受不了啦,看见麦场边上有一种灰色茎蔓叶片像鸡毛一样排列的草,拔下来嚼着吃了,下午叫人扶回家来了。她的肚子痛。知道是中毒了,她自己洗胃,把一块胰子嚼着吃下去了,还喝了水,恶心,呕吐,然后躺在炕上。到了半夜里,母亲不行了,要着喝了些水,又把我和两个妹妹叫到炕前,摸着我们的手断气了。母亲想说话的,但光是张嘴,舌头硬了,没说出话来。

我父亲回来之后,被队长组织积极分子批斗了两次也就算了,不再追究了。人们都说,家里没个大人咋行?

其实,我们家里藏着两缸苞谷哩,没叫搜粮队搜走。那粮还是我父亲和母亲1958年春天埋下的。那时候刚办集体食堂,队里叫把家里的粮交到食堂,说吃集体食堂呢;共产主义到了,楼上楼下,电灯电话,马上就要过好日子哩,家里存粮食干什么!父母亲交了一部分留了一部分。父母亲不懂什么共产主义,知道粮食是命根子,没粮食不得活。也可能我的父母思想就是反动,不相信共产主义到了的宣传,因为我家的成分是富农,按阶级斗争的理论来说本质就是反动的。

我父亲兄弟四个人,父亲是老大。我爷爷在马营镇城里开过商号。解放前爷爷就去世了,弟兄四个人就分家了。我父亲种地,家在马营镇城外住。我父亲是个好农民,庄稼种得好。我记得清楚得很,我父亲犁地,犁沟一行一行匀得很。他犁地的时候人总是走在犁沟里,一片地犁完了,你看不见一个脚印——每一趟犁铧翻过的土把脚印都盖上了。父亲说,犁地是庄稼人的脸,看你的脸清洁不清洁就知道你是不是个好庄稼人。

我父母藏苞谷我知道。我1947年出生,1958年十一岁了。藏苞谷的那一天夜里,我在大门口望风,我父母在后院的园子里挖坑。怕苞谷发霉,直接把两个缸埋进坑里了,上头压上麦草,再把土填上,扒平,种上了苦荞。第二年种了些扁豆,拔了扁豆又种上苦荞。搜粮队搜粮的时候,荞麦还开花着呢,他们根本就没想到长着荞麦的地里会埋粮食。他们拿着铁棍把院子、猪圈、厕所和住房都捣遍了,浆水[1]缸都用铁棍搅着看了。

1959年春天饿得难挨的时候我问过母亲:娘,腿饿软了,还不挖些苞谷吃吗?我母亲说不能挖,挨饿的日子在后头呢。

我母亲去世,父亲回来了,还是没吃那苞谷。我父亲说,不敢吃,叫队里知道就收走呢!那时候社员们还在喝食堂的清汤,家里不准冒烟。一冒烟队长和积极分子就来了,看你煮的野菜还是粮食。

到了旧历九月,父亲还是不叫吃苞谷,那时集体食堂已经关闭了,家家都煮野菜吃。父亲胆子小,父亲怕开批斗会,怕得要死。也真不能不怕,就是那一阵子,专区工作组在马营镇召开了万人批斗大会,在一个农民家挖出来了几十斤粮食。这个农民家的儿子是县委什么工作部的部长,工作组叫他儿子主持大会批斗父亲,说他父亲是阶级敌人,冒尖人物。什么叫冒尖人物?就是想发家的农民!那次批斗大会我父亲也去参加了,他回来说,会场上架着机关枪,民兵们手里提着明晃晃的大刀。我父亲怕得要命,怕把他也揪出来。唉,从打土地改革开始,我父亲就被人整怕了。土改的时候,民兵背着枪在我家门口转,怕我家转移财产,说是我家够地主条件。后来清查完了,定了个富农,但和地主分子一样对待,一开会就拉到前边站着,批呀斗呀,说是阶级敌人。动不动就踢两脚,打两拳。

到了腊月里实在饿得不行了,我的小妹妹不会走路了,走着路跌跟头。于是,一天夜里父亲起出来些苞谷。苞谷又不能生吃,太硬,又不敢动磨子,后半夜就煮了一锅,全家四口人围在炕上吃了。

过两天又吃了一锅。煮第三锅时有人进了我家,说你们生火煮啥呢,这深更半夜的?那人是队里的积极分子,平常不爱劳动,不下地,就知道跟着队长混吃混喝,是个二流子,全村的人都骂的人。他半夜里看见我家烟筒冒烟了。他掀开锅盖看见了苞谷,就去向队长报告了:何建元家有粮食!

何建元是我父亲的名字。

第二天开父亲的批斗会,整整开了一天。积极分子们——队长的亲信们,他们吃生产队仓库里的粮食肚子不饿——围成一个圈,炒豆子[2],撞人。队长拿着扁担在我父亲腰上打了几扁担。我亲眼看见的,头一天开批斗会我跟着去了。他们逼我父亲,叫我父亲交出藏下的粮食。

连着撞了两天,我父亲晚上回到家的时候鼻青脸肿,一只眼睛充血,眼睛肿得像桃子。鼻子也淌着血。走路一瘸一拐的。父亲跟我说,顶不住了,明天再斗就交待呢。我说父亲:你一交待,人家把苞谷拿走,全家人吃啥?等死吗?

但父亲还是坦白了。队长带着人来把苞谷挖走了,连缸都搬走了。

我问父亲:现在怎么办?

父亲说,没办法了,我不能叫人打死。

我说,不打是不打了,可是要饿死了!

父亲说,我家里不蹲了,我要饭去。

我问,我妹子怎么办?

父亲说,我管不了喽,一点办法没喽。

我说父亲你不能走,你走了我和两个妹妹怎么办?你把妹妹撂这里,我能有啥办法?我父亲说,没办法,我管不了这么多喽。他一边说,就一边把一床被子卷起来,外边裹了一块羊皮,捆好了。他说天一黑他就走。可是这天傍晚我们一家人正在喝荞皮汤,队长又进来了,看见行李了,说我父亲:何建元,你想跑吗?你想得好呀!你给我乖乖在家蹲着,你单要是跑,我叫人把你的腿打折呢!

队长走后,父亲就睡下了,就再也没下过炕。每天都睡着。我和妹妹去拾地软儿,撅蕨菜杆杆。地软儿泡软了和谷衣搀着煮汤喝。蕨菜杆杆剁碎炒熟磨面也烧汤喝;蕨菜面面粗得很,扎嗓子,但没毒。这样凑合了几天,我父亲说今晚上就要死了!叫我把他的长衫拿出来,他穿上,然后躺在炕上等死。可是第二天一天他也没喝汤,也没死,他就说:

我可能死不了。

他又把长衫脱了,放在箱子盖上。

就在他折腾活呢死呢把长衫脱了放在箱盖上的这天晚上,我小妹妹死了。小妹妹已经在炕上趴了好几天了。小妹妹瘦成一张皮了。小妹妹趴着睡,就像一块破布粘在炕上。就一直那么趴着,给些谷衣汤她就喝上,不给也不出声。后来她一口都喝不下去了,因为谷衣、荞皮汤喝上后她排泄不下来,掏都掏不出来。

我跟父亲说,我妹死了,你把她抱出去吧。父亲靠窗根睡着,他也是脸朝下趴着,没抬头,说:

放着去。

我没想到父亲会这样说话,我说,大,妹子没气了,硬硬的了,在热炕上放着能放住吗?不臭了吗?臭了怎么收拾?

父亲说,我的娃,你看着你大还能活几天?

我说,我猜不出你能活几天,也猜不出我和大妹妹能活几天,可是人只要活着,就不能和断气了的人一搭躺着。那臭哩呀。

我大又说,不等你妹子臭了,我也就早断气了。放着去吧。

我又说,我和大妹子还活着哩。

我大不出声了。

我看指望不着父亲,,就自己抱,但是小妹妹重得很,——不,不是重得很,是我身子太瓤了——我抱到门口就栽倒了。在台阶上坐着缓了一会儿,再抱……我终于把小妹妹抱到后院的花园里了,就放进积极分子们挖苞谷挖出来的那个坑里。我没力气埋上我妹妹,就随便用脚蹬了些土疙瘩下去。

过了一星期,大妹妹突然胖了起来,脸胖得脸盆那么大,我都认不出她了。

我听奶奶说过,人饿的时间长了脸要浮肿。我大妹妹浮肿了。人一浮肿腿就没力了,大妹妹不能跟我去拾地软儿了。我烧上些地软儿汤,她喝上半碗,在台阶上躺着晒太阳。

过几天队长到我家来,说要播种了,谁下地干活,给一碗洋芋。

我父亲不去。他在炕上趴着,跟队长说他起不来了。队长走后我说父亲:你哪里是起不来了,你是不想起。你起来了下地,到地里混去,干动干不动,队里不是给一碗洋芋吗?你就这么趴着等死吗?父亲说吃一碗洋芋也是死,不吃也是死。

我说吃一碗洋芋死得慢,不吃死得快。

我父亲骂我:你吃去,你吃去!你能活下你吃去,我就等死了。我父亲生我的气呢。他准备下的行李叫队长没收了,没能去要饭,认为是我报告队长了,我把他拦住了,害得他没走了。

我就去劳动了。我干的活是在地里打囫几[3]。旁人摆耧种小麦呢,我拿个长把把的木榔头把犁铧翻起的囫几打碎。木榔头轻得很,可那时候人乏得很,木榔头在手里重似千斤,每举起一次都要用完全身的力气。我实在打不动囫几,但又不得不混着打,坚持着,坚持着。坚持到中午收工的时候,出工的人到一冬天也没做过饭的食堂去,一人给了一碗洋芋——就几个洋芋。我至今记得清清楚楚的,蓝边的土碗,本地烧的。

就那几个尕尕的洋芋,我端在手里高兴得很:有吃的了,饿不死了!回到家我把洋芋给大妹妹吃,不给父亲。说实话呢,我父亲认为是我拦住他没出了门,生我的气呢,可我生父亲的气呢。人家的父母撩乱着给孩子找吃的,他在炕上躺着不动!但是,我和妹妹在台阶上吃洋芋,父亲在炕上趴着听见了,喊我的小名,说,真娃子,我吃个洋芋。我说,你不出工,我能叫你吃?

下午我还是打囫几。有时蹲在地上刨土,从犁沟里把前头人播下去的麦子刨出来捡着吃。队长看见了骂,我把你的手打折哩,你再刨!我就接着打囫几,等他走了接着刨犁沟,拾种籽吃。到晚上收工食堂又给了一碗洋芋。回到家我还给大妹妹吃,我也吃。这次我父亲不张嘴要了,他知道我不给他,但我给他拿一个过去,我说,吃吧,你。他接过去吃了。这天夜里,我大妹妹说口干得很,想喝水。家里没水,我到隔壁生产队的食堂去,敲门,说要点水,我妹子渴得很。食堂做饭的人睡了,不愿起,说没水。我只好提着瓦罐往河沟走。河沟离我家二里地,黑咕隆咚的,走着走着被什么绊倒了。用手一摸,是个死人。死人我也不怕,白天打水,看见过人们撇在河湾里的死娃娃。那时河湾里到处是死尸,我一点都不害怕。到了河沟又舀不上水:河沟冻冰着哩。我从沟边上找块石头砸冰也砸不开。那时候冰已经薄了,但我抱不动大石头,拿小石头砸。砸了很长时间砸下来一些小碎冰渣渣。我把碎渣渣捧到瓦罐里提回家来,这时天麻麻亮了。我赶紧烧水,没烧开,就是冰化开了,温嘟嘟的,端去叫大妹妹喝,大妹妹不会喝了。我给她灌也灌不进去了。我跟父亲说,父亲不管。他把长衫又穿上了,他说,我要死的人了,能管着她吗?

没办法。我大妹妹那年十岁,我试着往外抱没抱起来,叫个人来,把大妹妹拖出去了。还是拖到菜园里的那个坑里,和小妹妹埋在一起了。

我还是出去参加队里劳动,一天弄两碗洋芋吃。连着两天,我和父亲分着吃,一人一半。我想,是我的父亲呀,不要叫饿死了。我娘养下了我,但我是父亲养大的呀,为了一家人的生计,他吃了多少苦呀,现在我家就剩下我们父子两个人了,有一碗洋芋就两个人吃吧。

给父亲吃洋芋的第三天,我父亲突然就精神起来了,改变主意了,那天晚上他脱了长衫睡觉,说:

死不了啦,明天下地做活去。

看父亲精神起来,我很高兴,说,大,你不等死了?父亲说,一天有两碗洋芋,老天爷不叫我死呀!

早晨起来, 我看见父亲趴着不动弹。我想他又发懒了,又变主意不想出工了,就喊,大,你还不起?你说的今天干活去!我父亲不说话。我就又说,大,你说话不算话!说着,我推了他一把,才发觉已经硬硬的了。

我把父亲的长衫给套上了。这长衫是我父亲解放前家境好时做的长衫,那时爷爷还活着,经商,虽然父亲在家种地,但独当一面管着全家的农业生产,爷爷给他做的长衫。我母亲跟我说过,冬闲或者村里有啥事了,父亲就穿着长衫走来走去,应酬。农村合作化以后,父亲不穿长衫了,但他很爱惜,一直存放在箱子里。我父亲是我们村唯一穿过长衫的农民。

把长衫套上后我就去找队长,叫他找人抬出去埋掉。但队长没来,我就给父亲脸上盖了一张纸。放了三天,队长叫会计和保管来了,把我家的柳条耱子拿过来,把父亲抬上去,盖了床被子抬出去了。会计问我,你去不去?我回答走不动了,你们埋去吧。

埋完父亲的这一天,家里来了很多人,都是亲戚,还有街坊邻居。都是看我来的,说这娃孽障,没人管了。等他们走后,我发现铁锨没了,铲子没了,水桶没了,砂锅没了,连提水的瓦罐都不见了。在家一个人过了几天我就跑出去了……跑到公社去了。我听人说,那里有个幼儿院,专门收养没父母了的孩子。

1969年冬天,五大坪农场往饮马农场迁,我回了一趟家。我想把父亲的坟迁一下,问会计,问保管,你们把我父亲埋哪儿了?他们都说记不清了。他们说,队里死了人都叫他们抬,关门了[4]的都有好几家,成孤儿的就更多,都是他们抬的,他们也不记得抬出去埋哪儿了。

从那以后我再也没回过家。何至真结束他的家事的讲述。

我沉默无语。过一会儿才问,你两个妹子呢?还在菜园里埋着吗?

没有,那次回家,生产队已经把我家房子占了当队部。我叫他们把我妹子起出来迁到祖坟去了。当时有些亲房家的人不同意,说哪有女子埋祖坟的,媳妇才能进祖坟。我说,我不讲规矩,我就是要把妹子埋在祖坟里。天打五雷劈,叫它打我来,劈我来!

这天夜里,我与何至真聊天直到深夜。大约是凌晨一点钟的时候,他说该回去了。我挽留他:这间客房是农场领导安排的,就我一个人,你睡那张床。他不睡,说黄闸湾不远,骑车二十分钟就到了。非要走。我送他到兰新公路。这是中秋节过后几天,大半个月亮挂在天边,那残缺的一边像是狗啃得豁豁牙牙的。何至真骑着自行车的身影在月色下消失很久,我还在兰新公路上站着。很久才有一辆跑长途的汽车驶过来,车灯贼亮,晃花了我的眼睛。但是汽车过去之后,月色如水,洒在公路上,公路伸向幽暗朦胧的远方。残月就在那远方。

[1]西北地区老百姓家庭腌制的一种酸菜,以喝汤为主,调进饭里,还可以代醋。

[2]五六十年代农村“帮助”人的方式,将被帮助者置于中间,外围的人将其推过来搡过去,连踢带打。

[3]方言,土疙瘩,土块。

[4]方言,全家死光了。独庄子

黄家岔梁的蚰蜒小路上走下来一个人。

黄家岔梁是条绵延数十里的大山梁,南北向横亘在通渭县寺子川乡境内。黄家岔梁仅仅是这条梁在黄家岔村附近这一段的名称。黄家岔村北边和南边的山梁人们分段叫做毛刺湾梁、黄家湾梁、朱坡湾梁和鸭儿湾梁。这条梁的脊背比较平缓宽阔都开垦成了农田,而两边的山坡很陡,且有很多条倾斜而下的山冈和山沟,就像下垂的百褶裙。那些大的皱褶延伸到梁顶的地方往往形成一个较为平缓的塆子,这样的地方大都有个村庄,分别叫毛刺湾村,黄家岔村,朱婆湾村……

这条梁的东边和西边各有一条并行不悖几十里长的大山梁,东边的山梁有一个总名称董家山,西边的山梁也有个总名称段家梁。董家山和黄家岔梁中间是一条巨大的山沟叫董家沟。从黄家岔梁上看董家山的沟沟壑壑,一座一座的院落掩隐在一片一片的绿荫里,在午后的蜃气中若隐若显,若幻若真。10月中旬天已经很凉了,山坡地上的庄稼都收完了,地都犁过耙过了。树叶变黄了,草也黄了,只有一条一条的冬麦地绿茵茵生气勃勃的。已经是深秋了,太阳晒在身上也不暖和了,但是从黄家岔梁上走下来的这个人的脸上却淌着油腻的汗水。他不年轻了,一顶土苍苍的蓝色布帽遮不住鬓角上的白发。他穿着毛衣,怀里抱着一件绿色军大衣。黑皮鞋和裤腿上沾满了尘土。

他不熟悉这里的路。他已经快下到坡底了,山坡上有很多横的斜的人踏下的羊走下的蚰蜒小路,他站下来观察,似在选择该往哪边走。后来他横着翻过了一道小山冈,终于看见了山脚下的一座院落,才又滑着蹭着下到两道山冈之间的沟里,往那个院落走下去。

接近院落的时候,他就听见了狗叫,还看见一条狗在院子中间跳来跳去,仰着头狺狺地叫。狗叫声中一个小姑娘从靠着山坡的屋檐下跑了出来,站在院子中间看他,接着又走出一个老奶奶也仰着脸看他。

这个行人看见了狗和人,但他没出声,快速地下坡走到那个院子旁边。这时他的视线被院墙挡住了,他又绕到门口去。院门向着董家山的方向,关着的。

这是个独庄子[1],庄子建在两条不大的冈子中间的小塆子里。塆子里有几棵大柳树,树那边是一道雨水冲下的山水沟。庄子门口有一条小路延伸到山水沟里,沟不深,沟坡的半截有一个比笸箩大不了多少的水坑,周围是人工用石头砌成的坝。这是一眼泉,渗出的水很少,看样子也就只够这一户人家使用。泉那边才是淌雨水的山水沟。

山水沟往东延伸不足百米就突然变深变宽了,和巨大的董家沟连在一起了,山水沟两旁的山冈变成了平缓的坡地。坡地里种着冬麦。有几块地种过洋芋,已经犁过了也耙过了,地边上堆着黑黑的洋芋杆杆。

这个人又看了一眼院门,把手里的军大衣和一个人造革书包放在山水沟边上,然后沿着一条小路往下走,走到山水沟的又宽又深的沟口上,对着巨大的董家沟站着,看对面的董家山。后来他又在冬麦地里走来走去,并走进了耙过的洋芋地里。他像是在寻找什么,走走停停,时而仰着脸思考什么。很久之后他终于拍了拍手往回走,回到独庄子门口。他看见院门还关着,就又下了那道山水沟,从泉里撩水洗了洗手,捧着喝了几口,然后眼睛顺着泉边的一条路看,看那条小路下到山水沟底,又上了对面的山坡;那小路弯弯曲曲从山坡上往黄家岔梁攀援而去。

他的眼睛对着小路看了很久,当他再回头的时候看见院门开了,一个六七十岁的白头发老奶奶站在门口,身旁还怯怯地站着个五六岁的小姑娘。

那个人笑了一下,喊着问,大娘,这达是黄沟吧?

就是黄沟。这位客人,你在这达转着找啥哩?

那人不回答,又问,这达就住你一家人吗?

啊,这是个独庄子。你是从那达来的?你找啥哩?

没找啥,就是看一下。大娘,这门前头的地越来越少了。

就是呀,我们刚来的时间地还宽着哩,这些年山水把地冲走了。

你们是啥时间迁到这里来的?

二十年了吧。将将承包的时间我们就来了。队长说哩,这达有十几垧[2]地你们种去吧,我和老汉[3]就来了。那时间我们三口人。老汉说,这坡根里地气热,种啥啥成……

你们将将来的时候这达还有房子吧?

没了,那早就没了!那学大寨哩,队长叫拆过平掉了。喂,我说你,你是哪达的人,你怎么知道这达的事情?

那人犹豫了一下说,大娘,我原先在这达住过,就是这达的人。

老奶奶很久没说话,愣愣地站着,后来突然就尖叫了一声:

天爷呀,你是展家的后人呀……

啊,我就是展家的后人,我叫展金元,我大叫……

知道,知道。哎呀呀,你是稀客呀!快,快进家,进家了喝口水……老奶奶很热情,也很激动,一连声地邀请,还对身旁的小姑娘说,快叫大大。但小姑娘认生,不叫,紧着往老奶奶身后躲。

进了院子,又进了房子,老奶奶又叫展金元上炕。展金元也不客气地上了炕。老奶奶一边问这问那,一边又打发小姑娘去叫爷爷。老奶奶说,老汉拉柴去了,两边的塆子里还有些洋芋杆杆没拉回来。老奶奶在地下忙乱,把一个自制的小茶炉端过来放在炕头上。这是个薄铁皮做的桶桶,里头套了泥,炉口就两寸大,放在一个铁皮做成的盘子里。她又从台阶上拿来一束剁得很整齐的树枝点着放进炉膛,把一个白色但已经熏黑了的小茶缸倒上水坐上,放上茶叶。把一碟冰糖放在炕桌上。

金元,你说你叫金元?老奶奶又从灶房里端来一碟花馍放在炕桌上,她自己才在炕头坐下说,你先填补几口馍馍,你是远路上来的吧?等老汉来了,我再做饭。金元说,不要做饭,不要做饭,我吃些馍馍就行。在毛刺湾吃下饭的,在黄家岔坐了一会儿就过来了,还饱着哩。大娘,我打问些事,过一会儿还要到寺子川去哩。老奶奶说不知你问啥事哩?金元说,大娘,我想问的是你们搬到黄沟来是啥时间?怎么把房子落到这达了?我记得我家的老庄[3]在下头平坦的地方哩,你们咋不在平坦的地方盖庄廓?老奶奶说,对着哩,你家的老庄是在下头哩。我们盖房房的时间,你们的老庄连印印都看不见了,人们还说你家的院子里埋下人着哩,老汉说,我们还是避开亡灵吧,就把房房盖这达了。

茶已经煮好了,老奶奶往一个茶盅里放冰糖,再倒上茶,说,金元,你喝茶,你走渴了。这时,院里脚步声响,老奶奶又说,老汉来了。

一连声的跺脚,还有拍打衣裳的声音,金元要下炕,一个老汉进来挡住了:不要动,不要动。你是稀客!稀客!老汉也上炕了,老奶奶又放个茶盅在炕桌上,倒上茶。老奶奶说,这是展家的后人,在黄沟住下的。老汉说,知道了,我知道了。小孙女跟我一说我就知道了。早就听说过,你们一家人就剩一个娃娃一个老奶奶了,娃娃的名字叫金元……

我就是金元。你还记得我的名字?

长相记不清了,人还记着哩。我那时年轻,不操心旁人家的事,但还记得你娘的样子,瘦瘦的,黄黄的脸,领着个五六岁的娃娃,大老远的从黄沟到黄家岔的食堂打饭。那时间吃食堂,公社化……1959年我们一家人逃荒去了新疆,过两年回来,就听说你家剩一个娃娃了,还有个老奶奶,叫亲戚领走了,几十年没有消息。将才小孙女一说,我就想是你来了。你今年多大?

五十岁。

现在在哪达?

在酒泉。酒泉的哪达?

农场,在一个农场当农工,种地着哩。

你的情况咋相[4]?

凑合着好着哩。和这边一样,农场也承包土地了。我和女人承包了六十亩地,种啤酒大麦——就是做啤酒的大麦。

收入还好吗?

一年和一年不一样?种好了,市场价好了,一年能收入个两万;市场价格下来了,也就收入个一万元吧……

一万元!不好了还能收入一万?那就好得很呀!我们这达两年也收入不了一万元。

不一样,农场和家里种庄稼的方式不一样。农场种经济作物,啥值钱种啥。家里还是种麦子种洋芋,一斤麦子五角,一亩就是打上四百斤,不是才二百元吗,还有成本哩……老人喝茶,沉默良久改变了话题:金元,这些年你没来过黄沟吧?

这是第一趟。1966年和1976年到过寺子川,看姑父和娘娘[5]。两次我都要来黄沟,想把我大我爷往好埋一下,娘娘挡住了;娘娘说你去做啥哩?老庄都叫人平掉了,你爷和你大的坟都找不到了……

老人说,噢,看来你这趟来是给老汉迁坟来了?

有这想法。我大下场[6]时说过,叫我把爷爷埋好。几十年了,大的话在我心里装了几十年了,我现在也快老了,想着这次来把事办了。

老人又停顿了一下说,你还记得你爷你大埋在哪达了吗?

不记得,不是我埋的。娘娘说埋在菜园里了,还有我妹子。

老人放下手中的茶盅,看着展金元的眼睛说,金元,这事你怕是办不成了。六十年代学大寨,生产队把你家的老庄平了,种成地了。现在连个印印都没了。

我将才也看了,的确我也认不出来哪达是我家的老庄,哪达是菜园。我爷和我大埋在庄后的菜园里了。我就认出来了那八棵柳树;那时候才茶盅那么粗,是土改以后分了地,打院墙时我爷种上的;现在水缸一样粗了。还认出水泉来了,我在那里提过水……

老人说,当年的事你还记得吗?

记得一些,有些记不清了。那时间我才七岁。

你爷你大怎么下场的,还记得吗?

这事我记得清清楚楚的,烧成灰也忘不掉。

能说一下吗?

那说起来就长了,怕是来不及了,我还要去寺子川哩。我计划下的今天到黄沟看一下,看能找着我爷我大的坟不,然后赶到寺子川的娘娘家去。

你非要今晚上赶到寺子川吗?晚一天不中吗?晚一天……

不要走了,不要走了。今晚上站[7]我家,明早起来消消停停走,饭时候就到了。我问你,你今天怎么来的?

我从通渭城里出来坐的去会宁县的班车,在沙家湾下车又换上会宁去静宁的车到了党家岘子。到党家岘子就没车了,步行走到万家壑岘,再到刘家湾,到毛刺湾,再到黄家岔,再到黄沟。

我估计你就是从党家岘子来的,你经过黄家岔了嘛!你已经走了四十里路了,翻山越岭的,今天就缓下吧。寺子川二十里超过了,你们不走长路的人,猛一下走长了,腿痛哩。

也就二十里路,我攒劲儿走一下,天黑就到了。

你看你看,你还是见外嘛。你为啥攒劲儿走哩?你今晚站下,明天起来了消消停停走不好吗?再说,这里是你的老家嘛,我们也是乡亲嘛,我老汉实心实意留你哩……

盛情难却,展金元犹豫犹豫同意了。他说,老大大,那就要麻烦你了……

这有啥麻烦的。你是贵客,想请还请不到哩。再说,我着实想听你说一下你的家事。

要说我家的事呀,那还得从头说,可那时间的事情,有些记得,有些不记得了,有些记是记得,但当时搞不懂是咋回事。就拿我大上洮河来说,我记不清是啥时间走的,只记得那时候吃食堂了,我娘天天三顿往黄家岔食堂里去打饭,那时我大就不在家了。我问过娘,我大哪去了,这么长时间了,咋还不回来?我娘就光说你大上洮河了。上洮河做啥,娘也没给我说清楚。还有,我实在也记不清从啥时候开始饿肚子的,只记得一开始吃食堂,我娘从黄家岔提回来的是馍馍,有白面馍馍,有糜面馍馍,能吃饱。后来就光提回来洋芋疙瘩汤,清汤,就吃不饱了。再后来是麸皮汤,后来连麸皮汤也没了,我娘不去打饭了。我娘说食堂没粮了,食堂散伙了。队里没粮了,家里就更是没粮了!在我的记忆里,吃食堂的那两年,庄稼黄了的时候,队上就派很多人来收我家地里的庄稼,在我家门口的场上碾场。场碾完了,粮食全叫牲口驮走了,一颗粮都不给我家留,就留下些麦草和谷衣。因此食堂一散伙家里就没粮吃,我娘就拿谷衣煮汤全家人喝,再就是剥榆树皮煮汤喝。喝了几天树皮汤,有一天我二爸跟我爷我奶和我娘说,我们逃荒去吧,蹲在家里饿死哩。我爷不逃荒去,我爷说到哪里逃荒去,政府的政策是一样的,这里没粮吃了,外头也就没吃的了,你往哪达逃荒去!我娘一听二爸说逃荒去,吓了一跳,说这一大家人的,老的老小的小,怎么要馍馍去?等一等吧,政府看着饿死人了,还不放粮吗?二爸说,放粮,你等着放粮哩吗?上头的公购粮征不够着哩,谁给你放粮哩!家里没粮吃,我娘也心慌得很,惆怅得很,但她坚决不同意逃荒要馍馍去。她跟二爸说,就是要馍馍去,也要等你哥回来呀,回来了商量一下呀,哪能说走就走呀!再说大和娘上岁数的人了,眼看着天凉了,能出门吗?还是等你哥回来再看吧。我二爸说,嫂子,你等我哥回来再要馍馍去呀,那你就等吧,我可是要走!说这话的第二天,我二爸就走了,他怕我爷我奶不叫走,悄悄儿一个人走了。

我家那时八口人,爷爷、奶奶、二爸、我大和我娘,我,还有两个妹子。二爸一走,就剩下七口人了,我大还在洮河上。二爸没走的时候,我家还能喝上树皮汤。二爸年轻身体好,二爸到外头跑着剥榆树皮,剥了榆树皮全家充饥。二爸一走,我家连榆树皮都剥不上了!食堂一散伙,人们抢着剥榆树皮,大的厚的榆树皮剥光了!二爸走了以后,我跟着娘去剥榆树皮,只能在人家剥过的树枝子上剥些薄皮皮。树皮剥来后切成小丁丁,炒干,磨碎,煮汤喝。再就是挖草根根——草胡子根根,妈妈草根根辣辣根根,还有骆驼蓬。这些东西拿回来洗净,切碎,炒熟,也磨成面面煮汤喝。除了草根根骆驼蓬,再就是吃谷衣炒面,吃荞皮炒面。荞皮硬得很,那你知道嘛!磨子磨不碎,要炒焦,或是点上火烧,烧黑烧酥了,再磨成炒面。谷衣呀草根呀磨下的炒面扎嗓子,但最难吃的是荞皮,扎嗓子不说还苦得很,还身上长癣,就像牛皮癣,脸上胳膊上身上到处长得一片一片的,痒得很,不停地抠呀抠呀,抠破了流黄水。

食堂散伙才一个月,我爷就下场了。榆树皮草根根谷衣荞皮,这些东西吃了是能充饥,能填满肚子,可肚子胀得把不下来,把屎成了一个难关。通常,我娘给我奶奶掏,我娘也给我和两个妹妹掏。可是爷爷不叫人掏,我奶奶要给我爷爷掏,但爷爷不叫掏。每一次把屎,我爷都拿根棍棍到茅坑去,自己掏。爷爷上罢了茅坑,灰堆上就淌下一滩血。后来爷爷就不吃那些草根根榆树皮了,躺在炕上不动弹。我记得我娘专门煮了一点点扁豆面汤给我爷端去,哭着劝我爷:大,你要吃些呀,不吃饿死哩。我爷不吃,他说,吃上这碗汤也是个死,不吃也是个死,留下这碗汤吧,给我的孙子喝去。一天夜里,大概是半夜时间,我被奶奶说话的声音惊醒了,看见灯亮着,奶奶披着衣裳坐在爷爷身旁喊我娘:金元娘,你醒醒。娘醒了,一轱辘爬起问做啥哩?奶奶说,金元娘,你下炕舀碗浆水[8]去。你大将将[9]说他口干得很,想喝口浆水。我娘披着衣裳下炕舀了半碗浆水给奶奶。奶奶用一个木勺勺舀着喂浆水汤,爷爷的嘴张着,但奶奶喂了几勺勺,浆水都流到枕头上了。奶奶又叫我娘,说金元娘,你看一下,你大把喝上的浆水吐出来了。奶奶那时间眼睛麻了[10],我娘探着身子看了看,嗓子里带出哭音来了,说,娘,我大像是不中了。奶奶呜呜地哭起来,我娘也哭起来。

这天的后半夜,我们一家人再也没睡觉。奶奶和娘一哭,我也哭起来,两个妹妹也哭。我大妹妹那年五岁,小妹妹三岁。他们不知道爷爷下场了,她们被我奶我娘和我的哭声吓哭了。后来,还是奶奶先止住哭说,金元他娘,不要哭了……天明了你到庄里喊几个人来,把你大抬埋了。

我娘说,这没棺材嘛,阿么[11]抬埋哩?

奶奶说,这饿死人的年月,阿里[12]那么多讲究?把板柜的隔板打掉了装上,抬出去埋了吧。

娘再也没说话。天亮之后,娘就到黄家岔去了。

黄沟到黄家岔的这一截坡坡,我娘过去一个钟头能走来回。这时间我娘的身体瓤了,爬不动山,我娘走的时候跟奶奶说,娘,你不要急,我饭时候就回来了。可是娘走了也就一顿饭的时间,就急匆匆回来了。她的脸上汗津津的,神色慌慌张张的。奶奶惊讶得很,问你这么快回来了?你叫的人哩?娘慌慌张张地说,没找见队长。奶奶说,没找见队长,叫几个庄户人也行嘛。娘说,哪顾上叫人嘛,听说搜粮队进庄了!队长和会计叫公社叫走了,到外庄搜粮去了。奶奶说啥搜粮队?娘说,我也说不清,反正是县上来人了,专区也下来人了,还有公社的干部,到咱队来了,搜粮哩,要把各家的粮食搜走……

奶奶听娘这么一说,也慌了,叹息般地叫了一声天爷,然后说,快!快!你把柜柜里的那几斤粮……

我家原来存着不少陈粮的,有麦子,有扁豆、谷子,把房子地下的板柜装得满满的,可是头一年成立食堂叫队长领着人来背走了,说成立人民公社了,要过共产主义的好日子,家里不叫做饭了。还是我奶奶哭着喊着挖了几碗扁豆,有十几斤,装在一个布抽抽[13]里,放在炕上放着的一个炕柜里,和几件旧衣裳放在一搭儿存着,舍不得吃。只是爷爷奶奶吃谷衣吃草根把不下来的时候,我娘才在石窝[14]里踏[15]碎,煮些清汤叫我爷我奶喝。那汤都不叫我喝,我小妹妹才能喝上两口。扁豆就剩下七八斤了。

我娘把炕柜上的锁开了,拿出装扁豆的抽抽走到院子里去了。一会儿进来对奶奶说,娘,我放在草窑里了,用草埋起来了。奶奶说,好,放在草窑里好。我家的院子里有两间土坯垒下的窑,以前是圈牲口的,一间是放草料的。合作化以后牲口入社了,窑里堆的全是生产队分下的麦草麦衣添炕的[16]。但奶奶在炕上坐了一会儿又说,草窑里怕是藏不住吧,人家来了还不先翻草窑吗?娘说,那你说放在哪达呢?奶奶仰着脸瞪着房顶,思考着,良久说,拿来,你把抽抽拿来,放在被窝里,我不信他们连被窝都搜。娘叫了起来:娘,不行呀,被窝里最不保险。我听人说,搜粮队把几家的炕打了[17]搜哩,不叫人在炕上坐着。奶奶惊讶得睁大了眼睛说,是吗?有那么做事的吗?大冬天把炕打了人往哪达睡去?娘说,人家不管你在哪里睡呀!

奶奶不出声了,坐着,但仍在走心思,因为过了一会儿她又说,金元他娘,你把抽抽拿来,我把它揣怀里。他们总不搜身吧!

娘略一思考说,这倒是个好办法。他们来了不砸炕你就在炕上坐着,砸炕你就下来在台阶上坐着。

奶奶把她破烂的大襟棉袄掀开了,把装着扁豆的抽抽塞进怀里了,抱着抽抽坐着。但是,后来娘烧好了草汤全家喝完了,奶奶又不放心地说,金元娘,我心里还是不踏实:来人了叫我下炕,怀里揣着一抽抽扁豆,人家看出来哩。娘说,那你看放到哪里好?奶奶说,我想放在你大的怀里,下场了的人,他们不翻吧!我娘说,这办法好,这办法好。

于是,奶奶又从怀里拿出抽抽来,掀开昨天夜里缠在爷爷身上的一件破布单子,把爷爷硬了的手拉开,把抽抽贴着爷爷的腰放下,然后盖上了布单。一切都做好之后,奶奶看看爷爷,总觉得爷爷的身体有点异常——腰部有点宽,且鼓了起来。她不放心地又揭开了布单,把爷爷的腿抬起来,把抽抽放到爷爷的膝盖下边,拍打着摊平,再放下腿去,再盖上布单。这样一来,连我也看不出爷爷有什么异常了。

然后,我和奶奶、两个妹妹在炕上坐着。我娘忙着切草根根,炒草根根,炒荞皮,推磨……我们全家人忐忑不安地等着搜粮队来搜粮食。关于埋葬爷爷的事,谁也不再提起。

这样子过了三四天,始终也没人来我家搜粮,奶奶有点沉不住气了,说我娘:你去黄家岔看一下,这搜粮队怎么还不来,等得人心急。

娘就又到黄家岔去了。这次娘去的时间长,饭时候才回来。娘进了房子,不等奶奶问话就说,搜粮队走了,没人搜粮了。奶奶悬着的心终于放下来了,说,走了吗?走了好,走了好,唉呀,把我吓死了。就剩下几斤粮食了,叫搜走了可怎么活呀!她长长儿出了一口气,停了一会儿才又说,也怪了,这工作队怎么没来咱家呢?我娘说,知道咱家没啥粮呗!没油水!奶奶说,那你没找一下干部吗,叫他们派人把你大抬出去?娘说,找了。我这时间才回来,就是找人找的。找不上人。队长不在家,叫公社叫去四五天了,搜粮去了,没回来。听人说这次搜粮是大兵团作战,怕本地的干部抹不开情面,把旁的公社的干部调到黄家岔搜粮,把黄家岔的调到旁的公社搜粮去了。奶奶说,队长不在了再找一下会计嘛,叫会计派个人来嘛。娘说,找了,会计昨天刚回来,会计也调出去搜粮去了。我找到会计说我大下场了,你派几个人把我大抬埋一下,看见会计的娘在炕上坐着哭着哩。原来前两天来的工作队在会计家搜粮没搜出来,逼着叫他娘交出粮食来。他娘说没粮食,人家拿棍子把他娘的腿打折了。会计今早上回来,他娘说你不在家,人家把我的腿打折了。会计说,娘,你不要说了,我在外边也是这样干的。我进去的时候,会计正张罗着找人给他娘治腿,哪顾上咱家的事哩。

奶奶怔怔地坐了一会儿说,你叫几个熟人来一下也行嘛。娘说,我去了十几家,半个村庄都跑过来了,有的家里人跑光了,到外头要馍馍逃荒去了,有的人家院子和房子地下挖得一堆土一堆土的,——搜下粮的——一个个灰头土脸的正收拾房子着哩,谁还有心思管咱家的事!

那咋办呀,你大就这么在炕上停着吗?那臭下哩!

我也没办法,叫不来人嘛。我一个人抬不出去,就是抬出去了还要挖坑哩……娘说。娘坐着缓了一会儿,喝了点水,又说,先这么办吧,我们把大挪一下,挪到凉炕上去,过两天我再找人去。

于是,我娘用力,奶奶帮忙,两个人把爷爷推着翻了两翻,把爷爷从窗跟前滚到上炕上了。上炕没有烟道,不走火,温度低。

我家原先住两间房,爷爷奶奶和二爸住一间房,娘和我和我妹子睡一间房。二爸出走之后全家挤在一盘炕上睡觉,为的是节省添炕的。以前家里有牲口有羊,有驴粪羊粪,添炕的不缺。公社化以后没牲口没羊了,麦草麦衣少了,我娘也饿软了,拾不下添炕的了。把爷爷翻到上炕上之后,奶奶就睡到窗根去了,那个位置炕最热。我挨着奶奶睡,然后是两个妹妹,然后是我娘。娘那头是爷爷。

又过了三四天,我娘就又去了黄家岔,又没叫上人。娘告诉奶奶,找到队长了,队长说死人太多了,他管不过来,叫自己找人埋去。娘跟奶奶说,黄家岔村口的路上东一个西一个撇着没埋掉的死人,有大人,也有娃娃,人都走不过去。她看了那情景就再也没去叫人。娘说,叫啥人呀,黄家岔的人乱撇着哩,谁到黄沟给你抬埋人来!

奶奶静静地坐了良久才说,那就放着吧,等后人来了再说吧。

奶奶说的后人就是我大。于是我们全家人盼呀盼呀,盼着我大回来。我娘对我和妹妹说,你大回来就好了。我问娘我大回来就有吃的了吗?我娘说,你大会有办法的。

我都记不清了,忍饥挨饿吃草根子吃谷衣的日子又过去了多少,大概是两个月吧,我大回来了。后来我才知道那是腊月底的日子,也就是1960年元月的一天。

我记得特别深刻,那是一天的饭时候,我们一家人在炕上坐着,我娘正要下炕给我们煮汤去,突然院门被人拍得叭叭地响了两声。

我们家几个月没来过人了,连搜粮工作队都没进来,所以门一响全家人都惊了一下,都仰起了脸。连正闹着要吃奶的在我娘怀里闹腾的小妹妹都停止了哭闹。后来门板又响了两声,一个软软的声音喊开门来!娘就说了一声:

你大来了!开门去!

我还有点怀疑,因为这声音有点异常,不像我大的嗓门。我大那时候三十左右做事干脆利落说话嗓门很高……但我听见的声气像是个老汉。可我却毫不迟疑地下炕开门去了。

那时候,我娘的身体已经很瓤了,已经不能每天出去给我们拾地软儿挖草根,不能挖妈妈根了。我家两个月当中就吃了奶奶藏下的那七八斤扁豆,再就是谷衣和草根,荞皮。我们吃完了草根汤在炕上坐着,可我娘还要给我们烧汤和添炕,我小妹妹还要吃奶。娘的脸肿得像南瓜一样,脸皮薄得像透明的纸,里头就像是装的水,指头一捅就能捅破,水能淌出来的样子。她在家走路的时候慢腾腾的,要时不时地扶一下门框和墙壁,防止跌倒。

我大回家了,但他根本就不是原来的样子了,他的胡子长得像犯人,脸瘦得变了相,黄蜡蜡的,灰楚楚的,他的棉衣破得像个要馍馍的花子。我不敢认他。倒是他一个一个地叫我和妹妹的名字,抱我,抱妹妹。我大抱小妹妹,小妹妹吓得哭起来,奶奶对我大说,你看你看,这丫头天天喊大哩,你回来了她倒诧[18]得不行。

我大说,我走的时候她才一岁嘛。我大上炕坐下了。我大冻坏了。我娘去烧汤,奶奶和我大说话。我听明白他们说的话了:我大是得了肺病回来的,要不得病还不叫回来哩。他说在工地就知道家乡没饭吃了,因为许多人的家人没饭吃,往工地跑,投靠儿子和丈夫。所有去工地投亲的人都劝他不要回来,说回家就饿死哩。有人还说,通渭县一个姓白的副县长,老娘在家没吃的了,往工地去找儿子,饿死在陇西和渭源交界处的路上了。人们越是劝,我大越是放心不下家里人,硬是走着回来了。他在路上走了五天,白天赶路,夜间就住宿在沿途的农民家里。昨天夜里他住在寺子川一个人家了,今天一早往回赶。

我大还真给全家带来了一些新气象,这天中午我娘烧的榆树皮汤。我们已经好长时间没喝到这样香的汤了,榆树皮汤咽起来滑溜溜不扎嗓子,还有点甜味。喝着汤我娘说,这榆树皮炒面是专为我大留下的,她说她猜着我大过年一定要回家来的。我大笑了一下。

我大还真有办法。这天傍晚又喝了一顿榆树皮汤他就出门了,半夜才回来。一阵挖地的声音把我惊醒的。睁开眼,我看见我大和娘把地下的板柜挪开了,挖了个坑,把半口袋啥粮食放进去又埋上了,把板柜又挪回原地方。把挖出的土端出去倒了。后来我大上炕了,在我身旁睡下的时候说,娃娃,我去背了一些糜子,埋下了,还有半口袋胡麻,胡麻放在草窑里了。奶奶在窗根里坐着,担惊得很,一个劲地问,你从哪达背来的?你从哪达背来的?但是,第二天早晨我大睡在炕上起不来了,不停地咳嗽,吐出几口血。我娘拿个瓦盆接血。那血是黑颜色的,一块一块的就像浸住[19]了的血豆腐。大的脸黄得像张烧纸。奶奶在窗根里坐着抹眼泪,说,叫你不要出去,不要出去,你偏要出去。挣坏了吧……

我大的脸上泛起一层淡淡的笑容:娘,那些粮食够你们吃到春天,草长出来,苜蓿上来……苜蓿上来就饿不死了。

我大再也没有爬起来,他连着咯了两天血就咽气了。咽气之前把我叫到他的身旁说,娃娃,我不中了,有些事要跟你交代一下,你是我们展家的唯有的男子汉。你将来要把你的爷爷埋了。爷爷没棺材,等到你长大了做个棺材,把爷爷埋好。大不中了,没那能力了。我大说着话又咳嗽起来,又吐血,过一会儿不咳嗽了,又对我娘说,那口袋糜子你们先不要动,放好。你们先吃胡麻。你们一点一点拿着吃,糜子你们放好,要把荒年过去。黄家岔的黄福成你们要防着些。我和他一搭给冉家做过活[20],那人你们要防着不要叫知道咱家有粮,知道了一颗都剩不下。那人瞎账得很……

我大下场了,我娘还是没办法把我大抬出去,就像爷爷一样,推到上炕上和爷爷一排放着,脸上盖了一张纸。我们一家人挤在半截炕上睡觉。白天,我娘和我们在炕上坐着取暖,煮谷衣煮草根吃,到了夜里,娘就在爷爷以前喝罐罐茶的茶炉上炒胡麻在石窝里踏胡麻煮汤。胡麻有营养,虽然一次就喝半碗碗,但我的心踏实着哩,知道饿不死了。我娘在妹妹饿得哭的时候总说,不要哭,天黑了给你煮胡麻汤。

我娘不敢白天炒胡麻,也不敢夜里在灶房的炉灶上炒胡麻,爷爷还活着的时候,一看见烟筒冒烟,队上的积极分子就闯进来看锅里煮的啥。

但是,我大没了才七八天的一天的中午,黄福成还是闯进来了,还带着三四个年轻人。那天我娘正在灶房里烧荞皮汤,听见啪啪的打门声,就跑进住房对奶奶说声来人了,然后去开门。门一开,黄福成就进来大声嚷,人家的烟筒都不冒烟,就你家的烟筒冒烟,你家还特殊得很!说着他就直奔灶房揭开了锅盖,但他看见的却是一锅黑糊糊的荞皮汤。这时我娘说,黄队长,你给我说说,谁家的烟筒不冒烟?不冒烟就能把草根煮熟吗?但他不理,对那几个年轻人说,搜!给我搜!那几个人进了住房看见奶奶、妹妹和我在炕上坐着,爷爷和我大在半个炕上躺着,就又出门进了空荡荡的猪圈,进了草窑。

很快,他们就把麦草呀谷草呀从门口撇出来了,把半口袋胡麻翻出来了。我娘急了,扑上去夺,说这胡麻你们不能拿走呀,这是救命的呀!黄福成一脚就把我娘踢倒了,骂,驴日下的!我知道你们家没干好事!你男人一回来,仓库的粮食就少下了!不是你男人偷的才怪了!你说,你男人偷了多少胡麻?还有糜子?糜子藏到哪里了!

我娘哭着不出声。队长又骂:

说不说!你不说吗?搜,给我再搜!搜出来我把你的腿打断哩!

这帮人手里拿着镢头,锨,还有个人拿着一把斧头。他们在院子里这儿捣,那儿砸,听声音,觉出声音不对头就刨。他们把炕洞里都探过了,拿锨把带着火星的添炕的铲出来橵在院子里。后来又进了房子敲打。终于,他们把板柜下的半口袋糜子也挖出来了。黄福成又喊着骂,没冤枉你们吧,我没冤枉你们吧!我知道就是你们偷队上的粮了!掀过,把炕席掀过!把炕打了,看上炕上藏下粮食没有!

就在他们翻箱倒柜的时间,奶奶已经走到门外去了,坐在台阶上了,就是两个妹妹在炕上坐着。他们把妹妹从炕上撵下来,把爷爷和我大掀到奶奶经常坐的窗根前,然后揭起上炕的席子。

奶奶在台阶上坐着没动,我娘又冲进来了,喊着说,你们不能动死人呀,这不是造孽吗!但他们把我娘推开,细看炕坯有没有动过的痕迹。

他们没打炕,他们没发现藏过什么的痕迹,但他们走出房门之后,又在院子里站着朝四面看着。看着看着,黄福成像是又发现了什么,对坐在台阶上的奶奶说:

你,站起来!

奶奶颤颤巍巍地站起来了,拢着两手。黄福成又喊:

把前襟掀起!奶奶不动弹,奶奶的脸色变了,嘴唇抖起来,想说什么又说不出。黄福成走近两步抓住了奶奶的袖子一拉,把奶奶拢在一起的手拉开了。啪嗒一下,一个书包大小的抽抽从奶奶的大襟底下掉了下来,落在奶奶的小脚上。

黄福成拾起抽抽捏了一下,大骂:

你这个老熊,我说你今天这么老实——在台阶上蹴着!你把胡麻藏在怀里!你为啥不塞在裤裆里!

我也很是惊奇:不知道奶奶什么时间把几斤胡麻塞在怀里的。难道她知道有一天黄福成会来搜粮吗!

奶奶没说话,瞪着黄福成,她的脸色非常难堪,身体就像筛面一样地抖着。但是后来她猛地一跃,突然就抓住了黄福成手里的抽抽,喊着说,这几斤胡麻你要给我留下……

但是黄福成一甩胳膊奶奶就栽倒了。奶奶在地上呼天抢地嗥起来:

天爷呀,你不叫人活了……

黄福成领着人走了,把糜子和胡麻都背走了。他临走还说了几句话:今天就便宜你们了,你们老的老小的小……你儿子单要是不死,我非治他个盗窃公物罪,送到劳改队去……娘和奶奶把炕席铺好把爷爷和我大又翻着滚到上炕上。娘又抱了些麦草把炕烧一烧,把炕添上。这时天黑了,我们就睡了。这天我娘没做晚饭,我们一家人都没心思吃饭。就小妹妹哭着闹,喊饿。娘解开纽扣叫她咂奶,但她咂着咂着又哭起来,娘打了两巴掌,她又咂,咂着咂着睡着了。第二天我娘也没起来,就在炕上躺着。到了下午,两个妹妹都饿得哭,奶奶颤颤巍巍下了炕,烧谷衣汤。奶奶把汤舀好,一人一碗,我端到炕上,但我娘不喝,把我端的碗推开了。奶奶劝我娘:

金元娘,你要喝上些,你不喝哪行哩?我娘还是不喝,一动不动躺着,一句话也不说。

我娘在炕上躺了两天,这两天都是我奶奶摸索着烧汤,娘一口汤都不喝。第三天早上我娘爬起来了,因为这天夜里我小妹妹死了。小妹妹夜里总哭。没吃没喝的日子把我娘熬干了,她趴在我娘身上咂奶咂不出来就哭。我烦我妹子,娘都起不来了,她还没完没了地咂我娘的奶!我把她从娘怀里抱过来撇在炕角上了。我妹妹就像一只赖猫一样,吱啦吱啦地在墙角上哭着。天亮时不哭了,身体已经硬硬的了。

我娘把小妹妹抱到院子里用一团胡麻草包起来往外抱,身体摇晃着。我怕娘摔倒,跟着娘出去了。娘没摔倒,娘走上几步就站一下,站一下再往前走。走到去董家沟的坡坡上之后回头说了一句:你不要来。她又走了几步,下到董家沟的陡坡上去了,我看不见她了。娘为啥不叫我过去?我心里这样想着就又往前走了几步。这时我看见娘在陡坡上坐下了,点着了包着妹妹的胡麻草。我的心揪起来了,我娘烧我妹妹呢!前两天妹妹还活着,还要吃的,吃娘的奶,今天就要变成个黑蛋蛋了。我突然心里难受得很,后悔得很,后悔我没叫她吃娘的奶把她饿死了!还是这一年的春季,我跟娘去黄家岔食堂打饭,在路上看见过烧成黑蛋蛋的死娃娃。我很恐惧,问娘为啥要烧死娃娃?娘说怕狗啃了。那为啥不埋上?不叫埋。谁不叫埋?老辈子就这么始下的。那就那么撇着吗?它自己就化掉了。

我娘在陡坡下头坐了好长时间,我妹子都烧成黑蛋蛋了,火早灭了,她还在那达坐着。她的肿得亮晶晶的脸朝着董家沟的深沟大涧,看着沟那边的山山洼洼,看着山山洼洼里的白雪。那正是一年里最冷的日子,大雪把董家山盖住了。董家山的雪蓝盈盈的闪着光,和蓝幽幽的天空都连在一起了,分不清山头和天空了。她一动不动地坐着,坐了有小半天,才弯着腰手触着地站起来,我就赶紧跑回家了。

小妹妹的死像是把娘从睡梦中惊醒了,回到家中她就再也不睡了,给我们烧谷衣汤喝,她自己也喝。喝完之后,她又把门外台阶上早先洗净晒干的一堆草胡子和骆驼蓬抱进灶房在面板上剁碎。她的胳膊没力气,切刀在手里重如千斤,剁上几下就提不起了,她就停下来缓着,过一会儿接着剁。

转天我娘把剁碎的草胡子和骆驼蓬炒熟了,又放在磨子上推成炒面。她推上转上一圈就走不动了,但她缓上一下就又推。奶奶对她这种突然爆发出来的劲头困惑不解,说她:你缓着嘛,你这么急做啥?口袋里还有谷衣哩,吃完了再推。娘一句话不说,还是推。

推了两天,我娘把那一堆草胡子和骆驼蓬推成了炒面,和家里的谷衣拌在一起,装进一个毛口袋里。然后她又拿个瓦罐子到门外山水沟里的泉上提水。赶天黑前把水缸提满了。

就是这天晚上睡觉的时候,我娘坐在炕上对奶奶说,娘,我把炒面推下了,缸里的水也提满了,明天我想出趟门。奶奶问,你到哪达去?我娘说,我想出去要馍馍去。奶奶没出声,很久,我娘又说,娘,一家人在家里坐着等死,不如我出去一趟,我要上馍馍了来救你们。奶奶还是不吭声,凹陷的眼睛布满皱纹的脸花白的头发对着我娘。我娘也把她空荡荡的眼睛看着奶奶。

后来,我娘就躺下睡了。

转天早晨喝汤的时候,我娘对我说,元元,你和奶奶把家看好,把你妹妹看好,我出去要馍馍去。要上馍馍我就回来了。我心里明明白白的,家里没吃的,一家人坐着不动就得饿死,我说,娘,我跟你一搭儿去。娘说,你还小,你走不动,你和你奶奶把家看好,把妹妹看好,我出去半个月就回来了。

天亮起来喝完了汤,娘跟奶奶说,娘,我要走了。你把娃娃们看好。听说娘要走,大妹妹咧着嘴哭,也说要跟娘走,但奶奶把她抱住了,说,我的娃娃,你娘要馍馍去哩,你跟上做啥?你娘抱不动你,你也走不动。我没哭,我送我娘到门口,看着我娘下了门前的山水沟,又走上了去黄家岔梁的坡路。我娘说要往寺子川去,她走的不是去黄家岔村的路,走的是西边山坡坡上的那条路。那条路窄得很,也陡得很,拐来拐去的。我娘手里拄着个棍,一个手里还提着个手笼儿,里边放了一只讨饭用的粗瓷碗。她走上几步就站下来喘气,回头看我,招手,叫我回家去。我没回去,我站着看娘上山,我喊,娘,你慢些走,乏了就坐下缓一下再走。

我娘坐在山坡上了,缓着。过了一会儿她又站起来往上走。她缓一下再走,再缓一下再走,慢慢地转过一个塆子又转过一个塆子,走得再也看不见了,我才回家了。

我娘说,她出去要馍馍半个月就回来。我和妹子和奶奶等呀等呀,十五天过去了,没有回来。二十天过去了,也没回来。第二十天上,我大妹妹没有了。那是夜里,大妹妹在我和奶奶中间睡着,她说渴得很,说哥,我想喝口水。但这时我已经不敢下炕了。我娘走了以后,我奶奶给我们烧汤喝。后来奶奶也烧不成汤了,她下了地一走路就栽跟头。她趴在地上,在茶炉上给我和妹妹烧汤。烧汤好了,舀上,往炕上端,也是爬着挪。她还要添炕哩,也是爬着走,门坎都过不去;好不容易爬到炕洞门上了,添炕的又送不进炕洞里。后来,奶奶就不敢下炕了,怕下去上不来。我就下炕了,把娘磨下的炒面捧到炕头上,饿了就吃炒面,渴了喝水。那是大妹妹没的头一天,我下炕舀水,我也端不动碗了,一碗水端在手里,啪啦啪啦地抖,撒得剩下半碗。我上炕也上不来了,还是把一个木墩墩滚到炕跟前踩上爬上来的。所以大妹妹要水,我不敢下炕。奶奶也不叫我下炕,奶奶说,你下去上不来咋办哩?我拉不动你。那可冻死哩!天亮的时候我大妹妹断气了。她的头吊在炕沿上,人趴着,像一块破布搭在炕沿上。她的嘴里吐出来不多的一些白沫沫。我大妹妹那年五岁。

我和奶奶把大妹妹掀到上炕上去还费劲了!我们掀着滚到我大身旁了,可是他们三个人并排躺着占的地方太大了。奶奶说把爷爷再往炕柜那边搡一下,和我大挤紧一些,腾些地方出来。爷爷已经在炕上放了三个月了,他的脸皮都干干的了,胳膊腿也干干的了,肉皮就像牛皮纸贴在木头棍子上。爷爷变得轻轻的了,我和奶奶一用力就掀得翻过了,而这时我发现爷爷后背上的骨头扎出来了。原来爷爷的后背腐烂了。把爷爷、我大和我妹子摆着放好之后,我和奶奶就在炕上坐着等死。奶奶啥话都不说,我也啥话都不说。我心里明白得很,娘要是一两天能回来的话,我们就能活下,娘要是再不回来,出不去三天,我和奶奶就没命了,渴也得渴死!冻也得冻死!因为我和奶奶都下不了炕,就没人添炕了,也喝不上水了。炕一阵比一阵凉了。我和奶奶把能穿的都穿在身上,把两床被子围在身上,奶奶抱着我一动不动坐着。

你问我那时候想的啥吗?不想,啥也不想,想的就是要死了,像爷爷我大那样要死了。再想的就是娘为啥还不回来呀?她说的半个月回来,这都二十多天了,她为啥不回来?遇到啥事了?

也不害怕死。那时间心已经木下了,不害怕死。我大死了,爷爷死了,妹妹死了,黄家岔那么多人都死了,不是也没啥吗?我死了有啥可怕的。不过,有时一阵一阵的,也觉得死了有些可惜,我还没长大哩。人都是长大了,老了,才死哩,我还没长大就死掉,是有点可惜。但也没害怕死,心想,既然人一辈子要受那么多苦,还是死掉吧,死掉就不知道生活有多苦了。咳咳,就是这么随便想一想,也没深想。

那是我和奶奶在炕上坐着的第二天吧,中午时分,奶奶抱我的手已经抱不紧的时候,我家的大门被人推开了,院子里脚步声响。我的心当当地跳起来,心想是我娘回来了,她要上馍馍了,救我们来了。但脚步声到了台阶跟前,我又听着不像我娘,就没出声。接下来房门又推开了,进来一个生人。是个男人,大个子,瘦瘦的。那人可能是从阳光下走进房里看不清,站在地下看了一会儿才说话:你们还活着哩?你们是展家吗?奶奶回答就是,那人又说,我是寺子川的周家。你们在李家岔是不是有个亲戚?奶奶说我有个丫头给到寺子川了,在李家岔。那人说,我就是受你丫头的托付来看你们的,你们家里好着吗?那人已经适应房子里的光线了,就又哀叹起来:啊呀,这怎么齐刷刷地摆下了?奶奶说,这是我的老汉,这是大后人,这是孙女子,还有个孙女子没了,撇过了。活着的就剩我和这个孙娃子了,还有个媳妇出去要馍馍了……呜呜呜呜……奶奶说着就哭起来了。那人也唏嘘不已,但他说,老人家,不要伤心了,不光是你一家这样,我的一家人也饿光了。我这达拿着几个菜饼子,你和孙娃子先吃上,我们再说话。这人的穿衣有点怪,你说他是干部吧,一身农民的黑棉袄黑棉裤。你说他是个农民吧,棉袄上套着一件中山装的单褂褂。这人从他中山装褂褂的抽抽里掏出两个白面饼子,从那个抽抽里又掏出两个饼子。我接过一个咬了一口,原来是馅儿饼,是苜蓿馅子。奶奶吃了一口也吃出苜蓿来了,说,苜蓿长出来了吗?那人说,老人家,你多少日子没出门了?春天到了。奶奶说,我也不记得几个月没出门了,我的腿蜷上了,连炕都下不去了。说着话,那人又到外边去抱了柴来,给我们点火烧水,把开水端到炕头上,说,老人家,你喝些开水。这时候奶奶吃下一个饼子了,才问,好人,你是个啥人呀,你为啥这么伺候我?那人说,老人家,你问哩,我就把话说明,我是寺子川大队的人,我到李家岔检查工作,见到你的丫头了。她的婆家没人了,男人也没了。我就跟她说,你是个可怜人,我也是个可怜人,我的一家人也没了,老人没了,婆娘娃娃都没了,你要是愿意,我们就凑到一搭过吧。她说行呀,一搭过吧,我就把她领到我的家里去了。到家之后她跟我说,她是黄家岔村黄沟的人,不知家里还有人没有了,叫我来看一下。她想来看一下,就是腿软得走不动……

原来这个人是我的姑父,一下子我们就变得亲近了,奶奶就和他商量后事。姑父说,今天时间迟了,你们就先吃上些饼子缓着,明天我再来接你们。我给你们把炕添上。

姑父添了炕,又把开水给我们用一个瓦盆端到炕沿上放下,叫我们好喝水,然后就回去了。第二天天还没亮他就又来了。这次他又拿了几个苜蓿饼,还拿了一碗莜麦炒面。他烧了一锅开水,把炒面倒进去搅成稠糊糊,叫我和奶奶一人喝了两大碗,喝饱了。然后他说:

老人家,现在你们下炕,我们走,到我家去。

奇怪得很,昨天我和奶奶还下不了炕哩,吃了两顿好饭,我和奶奶竟然能爬出院子去了。爬到房背后的坡上之后,我竟然又能站起来了。只是腿软得很,心发慌,走上几步就栽跟头,就又跪下爬着走。然后休息,然后又站着起来走一截,然后又爬着走……

奶奶站不起来,就一直跪下爬着走,爬着走一截又跪着走一截儿……爬不动就坐下缓上一会儿。

从黄家岔梁往西,山梁长得很,过朱坡湾,过宋家庄。我们走到宋家庄的时候,奶奶实在爬不动了,我姑父就背她走。姑父的身体也瓤,背上一截放下来叫奶奶爬一截,再背……我们从鸭儿湾下了那大梁,就到了寺子川。这条路总共是二十几里吧,我们从太阳升起来走到日头落尽才走到姑父家。奶奶的棉裤在膝盖那儿磨破了,膝盖淌血了。

见到我娘娘,我们才知道姑父是大队书记,是省上派下来的工作组新任命的书记。姑父原先是寺子川大队副书记,以往工作中对社员好,不太粗野,所以任命了个书记。原来的书记队长那时都撤职了。我和奶奶在姑父家过了七八天。姑父是干部,那时一月供应十五斤粮。那时省上已经给通渭县放粮半个月了,但我们在黄沟不知道。救济粮一人一天二两到半斤,不一样。娘娘是吃四两。我和奶奶不是寺子川的,吃不上寺子川的救济粮,就吃姑父和娘娘的。姑父要工作哩,娘娘就每天去挖野菜,掐苜蓿。四个人凑合着吃。七八天以后的一天,我听见姑父跟娘娘说,他想把我送到义岗川公社孤儿院去。义岗川公社成立孤儿院了,孤儿院的娃娃们吃得好,政府还给穿的。

第二天我没和奶奶娘娘打招呼,就自己跑上到义岗川公社去了。寺子川村到义岗川公社大约三十华里的路,我一天就走到了。我是顺着金牛河边的小路走的。在姑父家吃了几天饭,我的腿已经有力量了,不栽跟头了。

展金元的讲述在这儿戛然而上。然后就是长时间的沉默。

展金元讲述家事过程中,黄沟的老汉老奶奶静静地坐着听,就问过几句话。他们的小孙女不知什么时候已经在热炕上睡着了。后来老汉才猛地叫起来:

哎呀,你看天黑了,黑黑的了!

是的,天已经黑透了,他们互相看对方脸部都不清晰了。老汉这才点煤油灯,对老奶奶说:

你看,你看,都啥时间了,你还不做饭去,咱们的客人饿坏了!

老奶奶如梦初醒,急忙下炕往灶房去了。老汉才对展金元说,喝茶,喝茶,哎呀,你看这火都灭了。他一边点茶炉一边问:

你娘再没回来?

没回来,一直没消息。

你奶奶呢?

过了两年,我奶奶叫二爸接走了,接到宁夏去了。那年二爸跑出去到了宁夏的固原,给一个人家当了招女婿。我工作以后回家探亲就是看奶奶,看娘娘,看姑父。我跟娘娘嘱咐过,叫她注意打听我娘回来过没有。我1966年回来过,那时我还在孤儿院呢,说是要分配工作哩,怕分远再回不来了,来看了一回娘娘和姑父。那次我问娘娘听到我娘的消息没有,娘娘说姑父每次到黄家岔梁都打问我娘。有一次听人说我娘死在华家岭的公路上了,有个人见过。姑父找到那人家里,那人又说是没这回事,他没说过这话。后来,我姑父劝我,娃娃你不要找了,你娘走出去就两种下场,一是死在哪达了,再就是跟了旁人了;如果是跟了旁人了,那就再不回来了,你找也找不见。但我不死心,每次见了娘娘都要问问有啥消息吗?我是这样想的:我娘就是跟了旁人,生活好了以后也该有个消息呀。她不想我吗?不想我妹子吗?老大大你说呢?

老汉不回答,静静地坐着,许久又问:

你爷爷和你大是谁埋了的?我和奶奶到了姑父家两天,姑父叫上人来把我爷我大收拾过了。姑父回到家说,埋在庄后的菜地里了。1966年那趟见到姑父,姑父说黄沟的庄子已经平掉了,庄子变成一片庄稼地,庄稼长得好得很!

我也没问过人,——没操过这心嘛——你家为啥独门独户住在这山根里?老汉又问。你们家要是住在大庄里,你大妹妹就能保住命,那时间已经放粮了!你们是个独庄子,没人管!

我长大以后奶奶告诉我的:我家原先是陇山乡人。家里穷,我爷到黄家岔这达给富汉扛活,富汉家在这达有一片地,叫我大给他种这片地。富汉家给盖的房房,叫我大在这达成家。解放以后土改,工作组把这片地划给我家了。

[1]方言,一户人家的村庄。

[2]一垧为二亩半。

[3]方言,定西地区把院落称庄廓、庄子,老院子叫老庄。

[4]方言,怎么样,如何。

[5]方言,姑姑。

[6]方言,去世,死亡。

[7]方言,休息,住宿。

[8]西北农民自制的酸菜,菜少汤多。

[9]方言,刚刚,才。

[10]方言,指严重的飞蝇症。

[11]方言,怎么,如何。

[12]方言,哪里。

[13]方言,小的布袋,或者衣服上的口袋。

[14]方言,石臼。

[15]方言,捣,砸。

[16]方言,烧火炕用的树叶、驴粪、杂草之类的总称。

[17]方言,砸了,拆了,挖了。

[18]方言,生分,害怕,诧异。

[19]方言,凝固。

[20]方言,扛长工。炕洞里的娃娃

上官芳每天早晨要锻炼一趟身体。她是十年前从地区人民医院退休的,那时候她才五十岁,在医院供应室工作,每天没完没了地煮针头、叠纱布、洗输液瓶。提前退休,是因为心脏不好,经常无端地心慌心跳,喘不上气来。那时候丈夫也已经退休,丈夫说两个儿子都成家了,你也就退了吧。从退休的第二天开始,丈夫每天早晨都陪着她锻炼一次身体。

锻炼身体也就是散散步:早晨从家里出来,走过立着一匹奔马雕塑的大十字来到东街,穿过繁华的商业街,走到南山新村;再慢慢地爬到南山的半山腰的南山公园,休息一下,俯视古老而又年轻的定西城;然后又下山原路返回家中。

走这么一趟要两个半钟头,可是她不觉得累,也不犯心脏病。原因是夫妇两人的确走得很慢,路程也不远。

这一天他们两口子折返到东街了,正在逛街,一个穿皮夹克的男人从地区医院的门诊部倒退着走出来,不看身后,仰脸看门诊部的二楼,把上官芳的脚踏了一下,还差点把她撞翻。她丈夫手快,一把扶住了她,并大声喊:

喂喂,怎么走路呢!

那人忙忙地转过身来道歉,哎呀,对不起对不起,我光顾看上头了。脚踏痛了吗?

脚踏痛了问题不大,撞翻了你负责任吗?

这时站在街边的一个中年妇女也替那个男人道歉:大娘,对不起,对不起,他光顾着找地方呢,往上看呢。

其实,那个男人只是踩着了上官芳的鞋帮子,并没踩痛脚,上官芳便说没关系没关系,找啥地方你们接着找吧。走,咱走。

说着话,上官芳拉着丈夫的胳膊又顺着人行道往前走。可是,那个男人紧走两步追上来了说,大娘,大娘,我听着你是本地人,跟你打听个地方你知道不?

上官芳站住了,转过身对着这个人。

我问一下,50年代末——就是1960年——这个地方有个儿童福利院,你知道不知道?

上官芳一怔,打量对方一下才说,你是找孤儿院吗?

对,孤儿院,那时候人们都叫孤儿院,其实正式的名称是定西专区儿童福利院。

你找孤儿院咋哩?

咋也不咋,就是看一下。

看一下?上官芳似问非问,又似自言自语,但她的眼睛在这个人身上打量来打量去,最后落在对方的脸上:这个人也就五十岁的样子,除了皮夹克,还戴一顶解放军的皮帽子,是兔皮的,咖啡色的皮毛,像个外地人,但说话又带着本地口音。她说:

你找孤儿院咋呢?你还真问对了,我就在孤儿院工作过。

您在孤儿院工作过?那人盯住了上官芳看,眼睛上下睃巡,突然说:

上阿姨,你是上阿姨吧?你不认识我啦?

上官芳怔了一下,困惑地摇头,反问,你是谁呀?

那人大声说:

我是秃宝宝!

上官芳又是一怔,接着笑了。这个五十岁的大汉竟然说出这样稚气难听的名字来!她笑着又说:

秃宝宝?你是秃宝宝?就是那个爱钻炕洞的秃宝宝?对对,我钻过炕洞,差点叫烟熏死。那男人以为她不相信,啪的一下摘掉了头上的帽子,并说:

你看,你看我是不是秃宝宝。

那人的头光溜溜的。不是剃过的那种秃头,是长过疮或者得过病的脱光了头发的那种秃头,除了后脑勺还有些稀稀落落的头发之外,其他部分一个伤疤又一个伤疤结痂以后锃光瓦亮的样子,一根毛都没有。

啊呀,你还真是秃宝宝,嘿嘿……上官芳咧着嘴笑,但她看见了路旁的几个行人站住了看她,看那个秃头,便有点难为情地说,戴上,你快把帽子戴上……

那个帮秃宝宝说话的妇女也有点脸红,笑着说你快戴上帽子吧,也不知道丢人!

秃宝宝也笑着,但他说,这怕啥呢,我就这么难看嘛!嫌难看你还找我咋哩?

上官芳又笑,说,秃宝宝,你咋认出我来了?我一点儿也认不出你了。

炕洞里的娃娃(2)

你咋能认识我嘛,那时候我还没现在一半高,才###岁嘛。不,还没到###岁。我是一进来就换肚子住院的,那时才七岁多一点儿。

你的眼睛尖得很,能认出我。

你没变嘛。你那时鸭蛋形的脸,现在还是鸭蛋形的脸。

怎么没变,四十年了,哪能没变?成老奶奶了。

成老奶奶我也能认出来。鸭蛋形的脸年轻不显年轻,老了不显老。再说,你嘴上的美人痣一看见就记起来了。

上官芳又笑:秃宝宝会说话了。

秃宝宝还笑:不是会说话,是真的。再说,我离开孤儿院是1969年,我都十六了,啥事不记得?上阿姨,你这是往哪里去呢?

回家去呢。我是出来遛早来了。

上官芳回答:这娃娃他大没了以后,自己还流浪了一段时间,走村串户要馍馍。走到哪里人们给吃的,可不愿收留过夜,——他身体瓤得不行,人家怕他死在人家的炕上。他常常钻进人家的炕洞里睡觉和取暖。进了孤儿院,有吃的有住处了,换上新棉衣了,可他还爱往炕洞里钻。钻进去唤都唤不出来。还有一个娃娃也爱钻炕洞,两个人一起钻一个炕洞。有一天两个人钻进去没出来,拉出来的时候两个人都晕过去了,烟熏的。那一个死了,他救活了。这娃娃命大!

就是命大。

[1]方言,傻瓜,不懂事。

[2]方言,疙瘩汤。

[3]方言,想办法,凑合。

[4]方言,一种如同牛毛草的植物,长得矮小,羊爱吃,其根白色,无毒。

[5]方言,石臼。

[6]方言,捣,砸。

[7]方言,旧度量衡,十六两为一斤。

[8]方言,家族血脉继承人,儿子。

黑石头

我是通渭县襄南乡黑石头的人。

黑石头是个很出名的村子。听老辈子的人说,一天夜里,随着呼隆隆的一声巨响,天上飞来两块神石落在村前的牛谷河边上。这两块石头一瘦一胖一高一矮,高的近乎一丈,矮的半人多长,黑黝黝铁疙瘩一样杵在地上。十里八乡的人们跑着来看,谁都不相信石头会飞。但时间不长,石头又飞了一次。一个妇女晚上收工回家,在牛谷河洗完了脚,把裹脚布晾在石头上没拿,她想第二天下地时再裹脚,不料去找的时候石头不见了。全村人惊了,到处去找,发现两块石头都杵在村后种谷子的坡地里。这下人们才相信了,这是一对神石。人们都说,神石被女人的不洁之物冲撞是不吉之兆,全村人都要遭受报应的。

黑石头有三个商号,一个是斗行,人们买粮粜粮的铺子;一个叫荣福祥,是个杂货铺,收土产品也卖土产品的商店;还有个字号叫钱永昌的,是个钱庄,给农民放款的。

荣福祥是我大大[1]家开的。我大弟兄三个,我大是老三;二大在县城当老师。

我大解放前也是经商的,在碧玉关有铺子。解放后政府给我大戴了顶地主分子帽子,赶回家来了。

1958年,我大上引洮[2]工地,我哥去靖远县大炼钢铁,我娘去大战华家岭[3]。到了第二年农历九、十月,生产队的食堂没粮食吃了,散伙了。

食堂没粮食吃了,家里就更没吃的了。从1958年开始公社化吃食堂以来,生产队就没给社员分过粮食;打场的时候县和公社的工作组就守在场上,打下多少拉走多少,说是交公粮交征购粮。就这,征购粮还没交够,工作组挨家挨户搜陈粮。

为了搜陈粮,把我们全家人都撵到二大家了。工作组在我家搜了三天,拿铁棍捣地,拿斧头砸墙。我跟村里的娃娃们跑进去看了,我家的院子里面挖出来几个窑,但没有搜出一颗粮食。我回家给我娘说了,娘说那是解放前没分家时我大大窖下粮的空窑窑,窑里的粮食土改时早就搞光了。

我二大家的院子也搜了,挖了十几个坑,连猪圈都挖了,也没挖出粮食来。二大的房子是临解放才盖的,二大是中学老师,家里根本就没有窖过粮。

食堂没散伙时,天天喝稀汤,食堂散伙后连汤都没处喝了,我娘就把谷衣[4]炒熟,磨细了,再把苜蓿根挖出来剁碎炒干磨成面,两搀和着打糊糊喝,当炒面吃。

食堂散伙一个月,我奶奶不行了。谷衣和草根吃下去排不出来,就是现在说的梗阻,我娘拿筷子给我掏粪蛋蛋,也给奶奶掏。我奶奶临断气的时候躺在炕上说胡话,喊大大、二大和我大的名字。那时我娘的身体也不行了,走路摇摇摆摆的,我娘就打发我去叫大大家的大嫂子。大大家的大哥会木匠活,结婚后分出去单过。那时大哥已经不在人世了,他背着木匠家什去外边做活,叫人谋害了。大嫂子不知道,还在家里守着。我找到大嫂子说,奶奶放命着哩,我娘叫你去看一下。一叫,大嫂子赶快拿了一块榆树皮做的馍馍到我家去,给奶奶吃。那时候榆树皮馍馍就是最好的吃头了!食堂一散伙,家家没吃的,抢着剥榆树皮。我娘身体弱没剥上。榆树皮切成碎疙瘩,炒干,再磨成面,煮汤。那汤好喝得很;粘乎乎的,放凉了吸着喝,一碗汤一口就喝下去了。你说怪不怪,我奶奶都昏迷了,说胡话了,可是大嫂子把榆树皮馍馍往奶奶嘴里一放,奶奶就不胡喊了,啃着吃开了。可是奶奶七十多岁了,早就没牙了,哪里嚼得动放凉了的榆树皮馍馍呀!我嫂子用刀切碎了给奶奶喂,我给奶奶灌水,奶奶就能嚼动了。喂着榆树皮馍馍,大嫂子说,奶奶怕是真不行了,我娘就把老衣给穿上了,就是裙子扣子没系住。我们那儿的风俗是老人死了要穿裙子,但不是现在的年轻人穿的那种裙子。

奶奶吃完那块榆树皮馍馍又活了三天,三天后再没吃的,就去世了。

当时我和我娘我奶奶睡在一盘炕上,奶奶睡在窗根离炕洞口近的地方,这儿炕热一些,娘睡在离炕洞口远的上半截炕上,我睡在奶奶和娘中间。睡到半夜里,娘把我推醒说,巧儿,奶奶没了。我娘又说,来,巧儿,咱们把奶奶抬到上炕上。奶奶那时干瘦干瘦的成了一把骨头,但我们没抬动。我没力气,我娘更没力气;我娘那时已经不能出门了,在家里走路要扶锅台,扶墙。我和娘在炕上跪着,从一边掀,把奶奶掀着滚了两下,滚到上炕上去了。

然后我和娘又睡下了。我娘没哭,我也没哭。那时候人死得多,看得也多,神经都麻木了,不知道哭,也不知道害怕。

天亮之后,我娘又说,巧儿,你出去叫个人去,不管谁家的,有大人了就叫来,就说奶奶没了,帮着抬埋一下。

黑石头是个很大的村子,人口稠得很,一、四、七的日子,左近二三十里的人都来这赶集。可是今年以来除去赶集的日子,街上根本就看不见人。很多人家的门上挂着锁子,没锁的人家也空荡荡的不见人。我到街上转了几家没锁门的人家,只有一家有人,是个姓毛的老奶奶在家里。我进了她家一间房一间房地找人,都是空空的。老奶奶看我乱窜,问我,巧儿,你做啥哩?我说毛奶奶,我奶奶没了,我娘叫我找个大人。毛奶奶说,巧儿,你奶走了吗?走了好,走了好。我看她洋混子[5]着哩,就大声说,毛奶奶你家的人呢?毛奶奶说,死的死掉了,活的就剩个福祥娃拾地软儿[6]去了。

我没找上人,回家告诉我娘,娘说,快上来,上炕暖和一下。我上了炕和我娘坐着。奶奶就在上炕上躺着。

时间快到中午了,我娘又说,巧儿,你再看一下去,毛奶奶家的福祥娃回来了没有。回来了就叫他找一下队长去,叫队上帮个忙。我下了炕正要走,突然听见院门被人拍得啪啪响。我心里一惊:这是谁知道奶奶没了!

娘说,快去开门!看谁来了!

我跑出去开门,原来是福堂哥来了。他是我奶奶娘家的侄孙子,二十来岁。他的脊背上还背着个背篓。我说福堂哥:你怎么来了?他说,我是来看看姑奶奶的。我说我奶奶没了,饿死的。福堂哥一听就跺脚:哎呀,我大怕姑奶奶没吃的,叫我送些吃的来。你看这还来晚了!

福堂哥进了房子,看奶奶停在炕上,我娘也在炕上坐着,就说,人已经没了,你们就这么坐着吗?也不找人抬埋?我娘说我出不去门了。我也说一早上就去找了,没找上人。福堂哥说他看看去。

福堂哥去街上转了一圈,也没找到人。他回来后说,我先回去,明天从碧玉叫几个人来。

第二天,奶奶的娘家来了几个人。奶奶的棺材是几年前我大就做好的,只是没有合卯,没刷漆。娘家人合了卯,白皮子棺材把奶奶抬出去埋了。埋在老坟旁的一条向阳的地埂子旁边,天冷,地冻上了,没法在祖坟里挖坑。

奶奶去世后,我和娘靠着福堂哥背来的东西将就着过日子。他的背篓里装了些晒干的萝卜叶子,萝卜叶子下面压着四五斤糜子,还有些烙熟的麻腐[7]饼子。我娘身体弱得下不了炕,家里一切都靠我:我把糜子在石臼里捣碎,捣成面面再煮成汤,放上萝卜叶子或是苜蓿根磨下的渣渣,和我娘喝。福堂哥拿来的东西大部分叫我吃了,我娘光喝汤不吃麻腐饼子。我叫娘吃,娘说你吃吧,你多吃些干的,我喝些汤就成了。我已经动弹不成了,你再不能饿垮了,里里外外都靠你哩。其实那年我才十岁。

我奶奶很惨。奶奶去世的时候,她的几个儿子都没有了。我大大是死在引洮工地的,挖土方的时候崖塌下来砸死的。二大是右派,送到酒泉的一个农场劳改去了,农场来通知说已经死掉了。我大娘外出讨饭,听人说饿死在义岗川北边的路上了,叫人刮着吃了肉了。我大是奶奶去世前一个月从引洮工地回家来的,是挣出病以后马车捎回来的,到家时摇摇晃晃连路都走不稳了,一进家门就躺下了,几天就过世了。我大临死的那天不闭眼睛,跟我娘说,巧儿她娘,我走了,我的巧儿还没成人,我放心不下。咱家就这一个独苗苗了。

我大为啥说这样的话哩?我哥比我大死得还早。我哥是1959年春上从靖远大炼钢铁后回到家的。###月谷子快熟的时候,他钻进地里捋谷穗吃。叫队长看见了,拿棒子打了一顿。打得头像南瓜那么大,耳朵里往外流脓流血,在炕上躺了十几天就死掉了。我哥那年整十八岁。还没成家。

那天,我娘对我大说,娃她大,你就放心,只要我得活,巧儿就得活。我大和我娘的感情特别好。我娘人长得漂亮。我娘是襄南乡的人,是我大做生意时看下的,看见我娘长得漂亮,叫媒人去说亲。谁知我外爷[8]不同意。我外爷家也是大户人家,但不封建,嫁姑娘要姑娘同意,我娘却不同意,嫌我大长得不俊。其实,我大长得不难看,就是皮肤黑,我娘看不上。可是我大就是看上我娘了,我大跟人说,非我娘不娶。后来他自己跑到我娘家里去说亲。旧社会哪有自己给自己说亲的,特别是在农村,那不成体统呀!可他把我娘感动了,我娘嫁给他了。

从哪里说我大和我娘感情好?我给你举一个例子:农村的家庭,谁见过男人给女人做饭的,尤其是光景好的人家!我大就给我娘做饭。我大和我娘结婚以后,我娘在黑石头侍奉我爷爷和奶奶,我大在碧玉关做生意,一两个月回家来住两三天;每次回到家里,我大就和面擀面做饭,不叫我娘动手。这是我娘自己给我说下的,解放前的事。我娘还说,就因为我大给她做饭,我奶奶还生气得很,说我大怕媳妇;我大就给我奶奶解释,我一年四季在外头,都是媳妇侍奉你,媳妇也辛苦嘛,我回家来了,做两顿饭她休息一下有啥不行的。解放后我大回家种地了,那就更是经常性地做饭了,因为我娘那时也下地劳动,收工回来就累得很了。我娘是娇小姐出身,从小没受过苦。

我再举个例子,我大去世后,我娘烧了七次纸,逢七就烧,七七四十九,烧了七次。现在看来烧七次纸没什么,家家都这样。可那是1959年的冬天呀,大量死人的时期呀,一般人家拉出去埋了,烧上一次纸就罢了,可我娘烧了七次。尤其是后来的两次,我娘走不动了,——那是奶奶死后的事了——娘是跪着挪到大门外,又挪到村外头,给我大烧纸的。

说起烧纸,我又想起一件事来。那是我奶奶去世后的两三天的一个晚上,那天又是我大去世后逢七烧纸的日子,不记得是四七还是五七,我娘说要给我大烧纸去。可她扶着墙走到大门口就再也走不动了,扑通跌倒了。还是我扶着她慢慢地走出巷道去的。我和娘烧完纸了,慢慢地走回来。那天我和娘进了院子关上大门,刚进房子,一个披头散发的人突然从院子里冲进了房子,拿个灰爪打我和我娘。我娘吓坏了,噢地叫了一声,往炕上爬。虽然天黑看不清这个人的面孔,但是我感觉出来她是谁了,就喊了一声:这不是扣儿娘吗!那人看我认出她来,扔了灰爪转身就走。我心想扣儿娘今儿是咋了,就跟出去了,一边走还一边问她:扣儿娘你打我咋哩?你打我娘咋哩?扣儿娘不说话,拉开门栓走出去了。我关上门回到房子,点上灯,看见娘的头钻在被窝里。我说娘,出来吧,扣儿娘走了。我娘掀掉被子看我,说我的头流血了。到现在我的前额上还有伤疤,在左边。我娘一边给我擦血,一边说我:你怎么这么大胆子,知道是扣儿娘还跟出去送她?我说咋了?我娘回答,她是想把我们娘母子打死,吃肉哩!我不信扣儿娘要吃我们,但我问我娘:庆祥说,扣儿娘把扣儿的弟弟吃了肉了,真事吗?娘长长地叹息一声没回答,半晌才说,门关好了吗?记住,以后不准你到扣儿家去。

过了十几天,福堂哥背来的菜叶子和粮食吃完了。家里一点儿能吃的东西都没有了,谷衣也吃光了,只好吃麦衣和荞皮。

连着两三年生产队不种荞麦了,嫌荞麦产量低,想吃荞皮也没有呀!我娘就把枕头里的陈荞皮倒出来吃。荞皮硬得很,吃起来很麻烦:拿火点着,烧焦烧酥了,叫我用石舀捣碎捣成面面。然后放在砂锅里倒上水煮,一边煮一边搅。那是草木灰呀,在水上漂着和水不融合呀。等搅得成了黑汤汤,大口喝下去。荞麦皮苦得很,就要大口喝,小口喝不下去。喝些荞麦皮灰然后一定要吃些地软儿什么的,否则就排泄不下来,肚子胀得要死。有一次,我趴在炕沿上,我娘拿筷子给我掏;痛得我杀猪一样叫,血把我娘的手都染红了。我哭着跟我娘说,娘,我再也不吃荞皮了,饿死也不吃了。我一哭,我娘也哭,娘说,我的娃,要死容易得很呀,我早就不想活了,可我死了,你也不得活呀。你不得活了,我咋给你大交待哩。

我好久没哭过了,我大去世的时候没哭,奶奶去世也没哭,但是这天为了吃不吃荞皮的事大哭了一场。原因是以前家里没了那么多人,我已经麻木了,也不害怕,因为我娘不管吃什么都多给我一点,我没有太挨过饿,没有想过自己会死,觉得有娘哩天大的事都能过去。而这几天吃下的荞皮差点把我胀死,我突然觉得死离我是这样的近,就像只隔着一张纸,一捅就破。而且我娘的痛哭使我觉察到了一个重要问题:我以为是保护人的我娘并不那么强大,相反很是软弱无力!巨大的恐惧揪紧了我的心:我才十一岁,还没长大,就要死去吗?就要像人们扔在山沟沟里的死娃娃一样叫狗扯狼啃去吗?这太可怕了!娘,我们就一点办法也没有了吗,真是要饿死了吗?哭了好久之后,我抽抽噎噎地说。我的心都在颤抖。

我娘这时已经不哭了,她目光呆滞滞地看着我。好久好久才说,巧儿,我的娃,你害怕死了吗?

我没回答我娘的问题,那一刹间,我感觉到我娘一眼看透我的灵魂了,看出我的恐惧了。不知是羞愧,还是害怕,我哑口无言。这时我娘又宽慰我说:

我的娃,你把心放宽,娘能把你养活了。

我长长地出了一口气。我说,娘,那我们吃啥呢?

我的娃,你到街上看一下去,今天是集日,看一下赶集的人多不多?

到集市做啥呢,你要买啥吗?我对娘的话很不理解,不愿动弹。可娘催我:

去嘛我的娃,你去看一下去,村西的那块空地上有没有卖木头买木头的人?要是有一堆一堆的木头,有人买,你就把他叫到咱家来。你跟他说,咱家有木头,比集上的便宜。

我还是不理解娘说的话,我说,娘,咱哪有木头,你能变戏法变出木头来吗?

娘说,咱家怎么没木头?下前川的房子拆了不是木头吗?

我心里一惊,说,娘,咱住的这房是二大家的,二大没了,二娘跑到陕西去了。要是二娘回来要房子,咱家的房子又拆了,咱到哪里去住哩?

娃娃,顾不得那么多了。有再多的家业也是闲的,把肚子吃饱,是顶要紧的。

尽管是灾荒年间,集市上仍然有稀稀拉拉赶集人。我和庆祥吉祥还有扣儿去牛谷河边的草滩上拾地软儿,总是从集上过,总看见卖馍馍卖油饼卖粮食和麸皮的人。卖馍馍的人把馍馍装在怀里,遇到要买的人就从怀里掏出来馍馍叫人看一下,接着很快就又塞进怀里。等对方把钱交了,他才摸出馍馍交给对方。一个馍二元钱,一个油饼四元钱,一斤小米七元。

但这天我没在这儿停留,我直奔买卖木头的地方。这地方也比前几年萧条多了,卖木头买木头的人稀稀拉拉的,新木头很少,人们都是买卖旧木头旧椽子的。

我在集市上转来转去许久,才鼓起勇气走到一个要买椽子的大人跟前,仰着脸说,大大,你要买椽子吗?我家有椽子,你要不要?那买椽子的人侧着身看我,惊奇地睁大了眼睛:你家的椽子在哪里,一根卖多少钱?我说价钱你跟我娘说去。我娘病了,在炕上睡着呢。

黑石头村在牛谷河边上一片很缓的山坡上,集市把村子分成上前川和下前川。我把那人领到上前川叫他去见我娘。那人进了院子四下看,没发现椽子,进房后问我娘:你们家的椽子在哪里?

我娘说,我们先谈价钱,价钱谈好了,你拆房子,房子在下前川,椽子是上等的松木。那人说要先看椽子,我就又领着他到下前川我家的房子去了一趟。我家解放后定为地主成分,四合院的房子没收了三排,给我家留下了一排四间房。看完房子,那人又去见我娘说椽子是上等的,但拆房子是个累活,一根椽子比集市上的便宜五角钱卖不卖?我娘说卖。

那人拆了八根,一个毛驴驮走了。这天下午我就买了六个谷子面馍馍回到家里。我娘说这六个馍馍得一斤半面才能蒸出来。六个馍馍我和我娘吃了三天。我把馍馍揉碎,和我拾来的地软儿煮成糊糊,一天喝一顿。一顿我喝两碗,我娘喝一碗。

下一个集日又卖了十六根椽子……后来,椽子卖完了,我娘 把三根大梁子也卖了,一根梁卖十元钱。多粗多大的梁呀,比我穿着棉袄的身子还粗。最后,我娘把我家的一盘石磨也卖了。买磨的来了两个人,是我看着他们把磨盘卸下来,滚到大门口,一辆架子车拉走了。卖这盘磨的钱买了十个谷子面馍馍。这样我和我娘就凑合到腊月底了。

正是一年里最寒冷的时间,家里又没吃的了。我娘的身体更加衰弱了,干脆就下不了炕了,天天在炕上不是坐着就是睡着。我娘的脸干干的了,眼睛塌成两个洞洞,脸腮也陷成两个坑坑。肉皮像是一张白纸。贴在骨头上。娘下不了炕就得我添坑了。我用扣儿娘打过我的灰爪——一个木头棍棍,前头钉了一块横着的木条条——把麦衣和秋天我娘从山沟里扫来的树叶干草推进坑洞,一天两次。每过两天,还要把死灰扒出来一次。这是我娘能动弹时教会我的。我娘说,丫头,你要学会添坑,我死了没人给你添炕,把你冻死哩。我不爱听娘说这样的话,她一说我就不添炕了,我说我不学了,你死了我就跟你一搭死去。这时我娘就哄我,说,死丫头,你还歹上[9]了。娘不死,娘要陪你过一辈子,可是你长大出嫁了还要我给你添坑吗?我说我不嫁人,我就跟你过一辈子。

并不会因为天气冷肚子就不饿了。不,天越冷肚子饿得越厉害,没办法,我跟着庆祥吉祥弟兄又去拾地软儿了。庆祥和吉祥是我三姨娘的娃娃。庆祥比我大两岁,吉祥比我小一岁。我娘跟我说,她嫁给我大不久,三姨娘也嫁到黑石头来了,给了钱永昌钱庄老板家的大少爷。三姨夫前两年因病去世了,三姨娘三个月前就死了。三姨娘生了三个儿子,大儿子几月前就跑到内蒙去了,两个小的现在大大家过日子。入冬后他们弟兄天天在沟里拾地软儿。他们的大大有个儿子在襄南公社粮管所工作,家里没死人。

冬天的地软儿特别不好拾。天旱,地软儿小得很,在草底下藏着不容易找到。但地软儿泡软了好吃,有营养,我和娘烧汤喝。

靠着拾地软儿过了半个月,我也饿得走不动了。正好这时供应救济粮了。

是生产队长王仓有到我家通知到大队背救济粮的。大队就在黑石头村里,我去背的,给我和娘四斤大米。

当时家里没有锅。头一年大炼钢铁,我家的锅呀铁壶呀,所有金属的东西都叫生产队搜走了,家里就剩下一个沙锅。也没有柴了。院子里只有一个不知啥时候挖下的树根,可我和我娘劈不开。我娘就把沙锅放在树根上,——由于有了大米,我娘精神大了,鼓起劲儿从房子里爬出来了——我娘叫我抱些麦草放在树根底下点着。我娘想把树根烧着,我们从两边吹气。树根上的树皮着了火,有了红火,后来麦草烧完了,红火又灭了。想煮米汤,水没烧开,米倒是泡软了,我们就喝了。

过了五六天,那几斤大米喝光了。这时候生产队的食堂又恢复了,一天叫社员打两次稀汤。我听人说,救济粮一人一天四两[10]的标准。四两粮能做什么饭,就只能喝两顿稀汤。