您的购物车目前是空的!

Selected English Poems

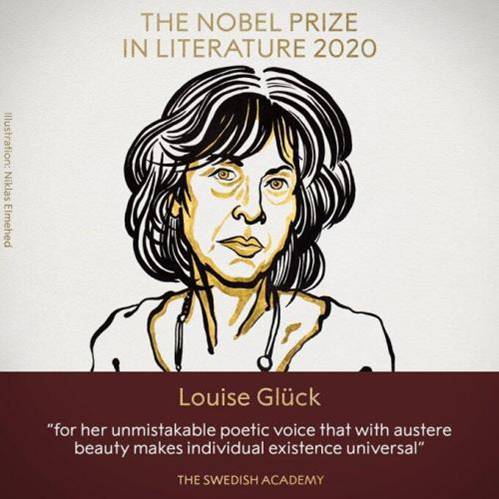

Louise Elisabeth Glück & Poems

- Louise Elisabeth Glück (pronounced “Glick”) was born April 22, 1943 in New York City and grew up on Long Island.

- Glück graduated in 1961 from Hewlett High School, in Hewlett, NY. She attended Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, New York, and Columbia University, New York City.

- Glück won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1993 for her collection The Wild Iris. Glück is the recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award (Triumph of Achilles), the Academy of American Poet’s Prize (Firstborn), as well as numerous Guggenheim fellowships.

- She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts and was previously a Senior Lecturer in English at Williams College in Williamstown, MA.

- In 2020 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, cited “for she unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal. ”

The Wild Iris

- At the end of my suffering

there was a door.Hear me out: that which you call death

I remember.Overhead, noises, branches of the pine shifting.

Then nothing. The weak sun

flickered over the dry surface.It is terrible to survive

as consciousness

buried in the dark earth.Then it was over: that which you fear, being

a soul and unable

to speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth

bending a little. And what I took to be

birds darting in low shrubs.You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again: whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice:from the center of my life came

a great fountain, deep blue

shadows on azure seawater.

野鸢尾

在我的痛苦尽头(一种典型的病人心态,痛苦源自于疾病纠缠)

有一扇门(这个门指的是“死亡”)

听我说:你称之为死亡(点明上文句的“门”的本意)

我记得。(“门”就是别人所说的死亡,所以说“你称之为死亡”)

头顶上,噪声,松枝变幻。(这是现实世界,听觉与视觉感知到的现实)

随即空无。微弱的太阳(现实是脆弱的,随时消失)

隐现在干涸的地面。(太阳无力,落于地面,典型的死亡意象)

生存是可怕的(作者再次代表美国病人发出呼喊)

当知觉(生命的意识)

埋藏在黑暗的土里(生命步入死亡)

然后终结:令你恐惧,成为(终结生命的死亡是令人望而生畏的)

一个灵魂,无法(人类幻想死亡之后可以有幽灵)

言语,仓猝结束,坚实的土地(死亡是突降的)

微微倾斜。而我带走的,将化作(死亡让世界歪倒了)

鸟儿跳跃在低矮的灌木丛(诗人幻想灵魂成为鸟儿继续生存)

已记不起这些的你(仍在现实中的你已经忘记了死去的“我”)

从另一个世界经过,(生死两隔,所以是另一个世界)

我告诉你我又能说话了:从遗忘中(实际上是灵魂借助那个鸟在吟唱)

返回的一切重又(灵魂重新返回人世)

找到一个声音:(另一种声音表达自我)

从我生命的中心涌出(灵魂的声音来自于生命的中心)

丰沛的源泉,蔚蓝的(声音如同水一样,汇聚起来)

海水上深蓝的阴影。(作者联想到这种声音如同海水一样丰沛。)

繁花盛开的李树

春天,从繁花盛开的李树黑枝条上

画眉鸟发出它例行的

存活的消息。这般幸福从何而来

如邻家女儿随意哼唱

却恰恰入调?整个下午她坐在

李树的半荫里,当和风

以花朵漫浸她无瑕的膝,微绿的白

和洁白,不留标记,不像

那果实,将在夏天的烈风里

刻上松散的暗斑。

赢得文学大奖的作家就是最好的作家吗?

美国得州小说家、诗人和评论家阿尼斯·什瓦尼(Anis Shivani)2010年曾开列了15位被高估的美国当代作家,其中第4号就是路易丝·格吕克(Louise Glück),1993年普利策诗歌奖得主,前任美国桂冠诗人。认为她或许是庸才当道的最佳范例;以对西尔维娅·普拉斯毫无生机的仿效出道,最终却由普拉斯愤怒的自白转向纯粹的家长里短,在琐事上故作忧愁,却对生死漠然视之;她单调的节奏往往被某些糊涂虫评论家误以为大度从容,实乃感情死亡后的心智麻痹。

“如果我们不识劣作,也便识不得佳作。”什瓦尼对平庸之作的定义:

劣作的特点是云山雾罩,自耀,自恋,缺少道德核心,以及文体凌驾于内容之上。佳作恰恰相反。劣作将注意力引向作者自身。此类作家背叛了现代主义的遗产,更不必说后现代主义。人终有一死令他们如坐针毡。他们对当今的重大主题保持沉默。他们渴望与政治毫无关系,他们功成名就。

J. C. Friedrich Hölderlin

Against a delightful blue(英译片段)

Against a delightful blue

However, the celestial beings who are always good

In all respects, like riches have these: virtue and joy.

A man is allowed to emulate that.

Is it allowed, when life is full of care,

To look up and say:

I, too, wish to be like that? Yes.

For as long as fellowship, in its purity, persists in the heart,

Man does not measure himself against the godhead unfavourably.

Is god an unknown quantity?

Is he as evident as is the sky?

This, I would sooner believe.

It is the measure of man.

Materialist, yet poetic, man lives upon this earth.

Yet the shade of the night with its stars is no purer,

May I say, than man;

He is named an image of the divine.

虽然,天堂至善至美,

褒有一切:丰裕、德行与愉悦。

世人或可效仿之。

在生活充满艰辛之际,

人总会禁不住仰天发问:

我只希望如此?

是。

只要有纯真的良善,内心坚持,

就会愉悦的以上苍之性来度己。

上苍隐约莫测难以感知?

上苍或如天宇一般清明?

我愿相信后者。

这是上苍为人立的度尺。

辛劳成就,

人,诗意的栖居在大地上。

我可以说,

星夜的投影,

也不比人更纯粹,

因为人会是上苍的影像。

In lieblicher Bläue blühet(德语原文节选)

Die Himmlischen aber, die immer gut sind,

alles zumal, wie Reiche, haben diese, Tugend und Freude.

Der Mensch darf das nachahmen.

Darf, wenn lauter Mühe das Leben, ein Mensch

aufschauen und sagen: so will ich auch seyn?

Ja. So lange die Freundlichkeit noch am Herzen, die Reine,

dauert, misset nicht unglücklich der Mensch sich

der Gottheit.

Ist unbekannt Gott? Ist er offenbar wie die Himmel?

dieses glaub’ ich eher. Des Menschen Maaß ist’s.

Voll Verdienst, doch dichterisch,

wohnet der Mensch auf dieser Erde. Doch reiner

ist nicht der Schatten der Nacht mit den Sternen,

wenn ich so sagen könnte,

als der Mensch, der heißet ein Bild der Gottheit.

Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night

- Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

- Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

- Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

- Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

- Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

- And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Thomas Stearns Eliot

Prelude I

- The winter’s evening settles down

With smells of steaks in passageways.

Six o’clock.

The burnt-out ends of smoky days.

And now a gusty shower wraps

The grimy scraps

Of withered leaves across your feet

And newspapers from vacant lots;

The showers beat

On empty blinds and chimney-pots,

And at the corner of the street

A lonely cab-horse steams and stamps.

And then the lighting of the lamps.

Kahlil Gibran · جبران خليل جبران

Seven times have I despised my soul

- Seven times have I despised my soul:

The first time when I saw her being meek that she might attain height.

The second time when I saw her limping before the crippled.

The third time when she was given to choose between the hard and the easy, and she chose the easy.

The fourth time when she committed a wrong, and comforted herself that others also commit wrong.

The fifth time when she forbore for weakness, and attributed her patience to strength.

The sixth time when she despised the ugliness of a face, and knew not that it was one of her own masks.

And the seventh time when she sang a song of praise, and deemed it a virtue.

William Butler Yeats

W.B. Yeats,1865~1939,其墓志铭是其晚年作品《Under Ben Bulben》最后一节最后一句:

Cast a cold eye,

on life, on death,

horseman,

pass by!

“冷眼一瞥/生与死/骑者/且前行!”

曾于1923年获得诺贝尔文学奖,获奖理由是:”inspired poetry,which in a highly artistic form that gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation”。

The Lake Isle of Innisfree

- I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

- And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

- I will arise and go now, for always night and day,

I hear the lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements gray,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

When You Are Old

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look,

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how love fled,

And paced upon the mountains overhead,

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

Alfred Tennyson

The Eagle: A Fragment

- He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ring’d with the azure world, he stands. - The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

该诗系作者为怀念亡友H.Hallam而作。

ULYSSES

- Come, my friends.

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

…… - For my purposes holds

To sail beyond the sunset,and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die. - ……

And though we are not now that strength which in old days moved earth and heaven that which we are, we are.

One equal temper of heroic hearts made weak by time and fate, but strong in will.

To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield.

John Donne

No Man Is An Island

No man is an island,

Entire of itself;

Every man is a piece of the continent,

a part of the main.

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less,

as well as if a promontory were,

as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were:

any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind,

And,therefore,

never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

William Blake(1757-1827)

“I know that This World is a World of IMAGINATION & Vision.”

“The Nature of my Work is visionary imaginative.”

The Sick Rose

- O rose, thou art sick!

The invisible worm

That flies in the night,

In the howling storm,

- Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy,

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

Auguries of Innocence (brief)

To see a World in a Grain of Sand,

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand,

And Eternity in an hour.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The Rime(rhyme) of the Ancient Mariner 古水手之歌

Part I

It is an ancient mariner

And he stoppeth one of three.

——”By thy long grey beard and glittering闪亮 eye,

Now wherefore(why) stoppest thou me?

The bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

Mayst hear the merry din.”

He holds him with his skinny hand,

“There was a ship,” quoth(said) he.

“Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard花白胡子 loon疯子!”

Eftsoons(soon) his hand dropped放开 he.

He holds him with his glittering eye——

The wedding-guest stood still,

And listens like a three-years’ child:

The mariner hath his will.

The wedding-guest sat on a stone:

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed mariner.

“The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the lighthouse top.

The sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he!

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea太平洋.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon——”

The wedding-guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

The bride hath paced into the hall,

Red as a rose is she;

Nodding their heads before her goes

The merry minstrelsy.

The wedding-guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed mariner.

“And now the storm-blast came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong;

He struck with his o’ertaking wings,

And chased us south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe,

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

Listen, stranger! Mist and snow,

And it grew wondrous cold:

And ice, mast-high如高墙, came floating by,

As green as emerald.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken——

The ice was all between.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

At length did cross an albatross,

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.

It ate the food it ne’er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder-fit;

The helmsman steered us through!

And a good south wind sprung up behind;

The albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white,

Glimmered the white moon-shine.”

“God save thee, ancient mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!——

Why lookst thou so?” “With my crossbow

I shot the albatross.

Part II

The sun now rose upon the right:

Out of the sea came he,

Still hid in mist, and on the left

Went down into the sea.

And the good south wind still blew behind,

But no sweet bird did follow,

Nor any day for food or play

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

And I had done an hellish thing,

And it would work ’em woe:

For all averred, I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.

Ah wretch! said they, the bird to slay,

That made the breeze to blow!

Nor dim nor red, like an angel’s head,

The glorious sun uprist:

Then all averred, I had killed the bird

That brought the fog and mist.

‘Twas right, said they, such birds to slay,

That bring the fog and mist.

The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free;[he furrow streamed off free]

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.

Down dropped the breeze, the sails dropped down,

‘Twas sad as sad could be;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea!

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deeps did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The death-fires danced at night;

The water, like a witch’s oils,

Burnt green, and blue and white.

And some in dreams assured were

Of the spirit that plagued us so;

Nine fathom deep he had followed us

From the land of mist and snow.

And every tongue, through utter drought,

Was withered at the root;

We could not speak, no more than if

We had been choked with soot.

Ah! wel-a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the albatross

About my neck was hung.

Part III

There passed a weary time. Each throat

Was parched, and glazed each eye.

A weary time! A weary time!

How glazed each weary eye,

When looking westward, I beheld

A something in the sky.

At first it seemed a little speck,

And then it seemed a mist;

It moved and moved, and took at last

A certain shape, I wist.

A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist!

And still it neared and neared:

As if it dodged a water sprite,

It plunged and tacked and veered.

With throats unslaked焦渴, with black lips baked,

We could nor laugh nor wail;

Through utter drouth all dumb we stood!

I bit my arm, I sucked the blood,

And cried, A sail! a sail!

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

Agape they heard me call:

Gramercy! they for joy did grin,

And all at once their breath drew in,

As they were drinking all.

See! see! (I cried) she tacks no more!

Hither to work us weal;

Without a breeze, without a tide,

She steadies with upright keel!

The western wave was all aflame.

The day was well nigh done!

Almost upon the western wave

Rested the broad bright sun;

When that strange shape drove suddenly

Betwixt us and the sun.

And straight the sun was flecked with bars,

(Heaven’s mother send us grace!)

As if through a dungeon grate he peered

With broad and burning face.

Alas! (thought I, and my heart beat loud)

How fast she nears and nears!

Are those her sails that glance in the sun,

Like restless gossameres?

Are those her ribs through which the sun

Did peer, as through a grate?

And is that woman all her crew?

Is that a Death? and are there two?

Is Death that woman’s mate?

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

Her locks were yellow as gold:

Her skin was as white as leprosy,

The nightmare Life-in-Death was she,

Who thicks man’s blood with cold.

The naked hulk alongside came,

And the twain were casting dice;

‘The game is done! I’ve won! I’ve won!’

Quoth she, and whistles thrice.

The sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out:

At one stride comes the dark;

With far-heard whisper, o’er the sea,

Off shot the spectre bark.

We listened and looked sideways up!

Fear at my heart, as at a cup,

My lifeblood seemed to sip!

The stars were dim, and thick the night,

The steersman’s face by his lamp gleamed white;

From the sails the dews did drip——

Till clomb above the eastern bar

The horned moon, with one bright star

Within the nether tip.

One after one, by the star-dogged moon,

Too quick for groan or sigh,

Each turned his face with ghastly pang,

And cursed me with his eye.

Four times fifty living men,

(And I heard nor sigh nor groan)

With heavy thump, a lifeless lump,

They dropped down one by one.

Their souls did from their bodies fly——

They fled to bliss or woe!

And every soul, it passed me by,

Like the whizz of my crossbow!”

Part IV

“I fear thee, ancient mariner!

I fear thy skinny hand!

And thou art long, and lank, and brown,

As is the ribbed sea-sand.

I fear thee and thy glittering eye,

And thy skinny hand, so brown.”——

“Fear not, fear not, thou wedding-guest!

This body dropped not down.

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men, so beautiful!

And they all dead did lie:

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on; and so did I.

I looked upon the rotting sea,

And drew my eyes away;

I looked upon the rotting deck,

And there the dead men lay.

I looked to heaven, and tried to pray;

But or ever a prayer had gushed,

A wicked whisper came, and made

My heart as dry as dust.

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

Till the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

The cold sweat melted from their limbs,

Nor rot nor reek did they:

The look with which they looked on me

Had never passed away.

An orphan’s curse would drag to hell

A spirit from on high;

But oh! more horrible than that

Is the curse in a dead man’s eye!

Seven days, seven nights, I saw that curse,

And yet I could not die.

The moving moon went up the sky,

And nowhere did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside——

Her beams bemocked the sultry main,

Like April hoar-frost spread;

But where the ship’s huge shadow lay,

The charmed water burnt alway

A still and awful red.

Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! No tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware:

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

The selfsame moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

Part V

Oh sleep! it is a gentle thing,

Beloved from pole to pole!

To Mary-Queen the praise be given!

She sent the gentle sleep from heaven,

That slid into my soul.

The silly无助的 buckets on the deck,

That had so long remained,

I dreamt that they were filled with dew;

And when I awoke, it rained.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams,

And still my body drank.

I moved, and could not feel my limbs:

I was so light——almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed ghost.

And soon I heard a roaring wind:

It did not come anear;

But with its sound it shook the sails,

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air bursts into life!

And a hundred fire-flags sheen,

To and fro they were hurried about!

And to and fro, and in and out,

The wan stars danced between.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge;

And the rain poured down from one black cloud;

The moon was at its edge.

The thick black cloud was cleft, and still

The moon was at its side:

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning fell with never a jag,

A river steep and wide.

The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on;

Yet never a breeze up-blew;

The mariners all ‘gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do;

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools——

We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother’s son

Stood by me, knee to knee:

The body and I pulled at one rope,

But he said nought to me.”

“I fear thee, ancient mariner!”

“Be calm, thou wedding-guest!

‘Twas not those souls that fled in pain,

Which to their corses came again,

But a troop of spirits blessed.

For when it dawned——they dropped their arms,

And clustered round the mast;

Sweet sounds rose slowly through their mouths,

And from their bodies passed.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the skylark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

And now ’twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel’s song,

That makes the heavens be mute.

It ceased; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Till noon we silently sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

Under the keel nine fathom deep,

From the land of mist and snow,

The spirit slid: and it was he

That made the ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune,

And the ship stood still also.

The sun, right up above the mast,

Had fixed her to the ocean:

But in a minute she ‘gan stir,

With a short uneasy motion——

Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound:

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell down in a swound.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare;

But ere my living life returned,

I heard and in my soul discerned

Two voices in the air.

‘Is it he?’ quoth one, ‘Is this the man?

By him who died on cross,

With his cruel bow he laid full low

The harmless albatross.

The spirit who bideth by himself

In the land of mist and snow,

He loved the bird that loved the man

Who shot him with his bow.’

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honeydew:

Quoth he, ‘The man hath penance悔罪自罚 done,

And penance more will do.’

Part VI

FIRST VOICE

‘But tell me, tell me! speak again,

Thy soft response renewing——

What makes that ship drive on so fast?

What is the ocean doing?’

SECOND VOICE

‘Still as a slave before his lord,

The ocean hath no blast;

His great bright eye most silently

Up to the moon is cast——

If he may know which way to go;

For she guides him smooth or grim.

See, brother, see! how graciously

She looketh down on him.’

FIRST VOICE

‘But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind?’

SECOND VOICE

‘The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.

Fly, brother, fly! more high, more high!

Or we shall be belated:

For slow and slow that ship will go,

When the mariner’s trance is abated.’

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather:

‘Twas night, calm night, the moon was high;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel-dungeon fitter:

All fixed on me their stony eyes,

That in the moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never passed away:

I could not draw my eyes from theirs,

Nor turn them up to pray.

And now this spell was snapped: once more

I viewed the ocean green,

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen——

Like one, that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breathed a wind on me,

Nor sound nor motion made:

Its path was not upon the sea,

In ripple or in shade.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring——

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too:

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze——

On me alone it blew.

O dream of joy! is this indeed

The lighthouse top I see?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own country?

We drifted o’er the harbour bar,

And I with sobs did pray——

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway!

The harbour bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn!

And on the bay the moonlight lay,

And the shadow of the moon.

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less,

That stands above the rock:

The moonlight steeped in silentness

The steady weathercock.

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were:

I turned my eyes upon the deck——

O Christ! what saw I there!

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat,

And, by the holy rood!

A man all light, a seraph man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph band, each waved his hand:

It was a heavenly sight!

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light;

This seraph band, each waved his hand,

No voice did they impart——

No voice; but oh! the silence sank

Like music on my heart.

But soon I heard the dash of oars,

I heard the pilot’s cheer;

My head was turned perforce away

And I saw a boat appear.

The pilot and the pilot’s boy,

I heard them coming fast:

Dear Lord in heaven! it was a joy

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third——I heard his voice:

It is the hermit good!

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

He’ll shrieve my soul, he’ll wash away

The albatross’s blood.

Part VII

This hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with mariners

That come from a far country.

He kneels at morn, and noon, and eve——

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak stump.

The skiff boat neared: I heard them talk,

‘Why, this is strange, I trow!

Where are those lights so many and fair,

That signal made but now?’

‘Strange, by my faith!’ the hermit said——

‘And they answered not our cheer!

The planks look warped! and see those sails,

How thin they are and sere!

I never saw aught like to them,

Unless perchance it were

Brown skeletons of leaves that lag

My forest-brook along;

When the ivy tod is heavy with snow,

And the owlet whoops to the wolf below,

That eats the she-wolf’s young.’

‘Dear Lord! it hath a fiendish look,’

The pilot made reply,

‘I am a-feared’——’Push on, push on!’

Said the hermit cheerily.

The boat came closer to the ship,

But I nor spake nor stirred;

The boat came close beneath the ship,

And straight a sound was heard.

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reached the ship, it split the bay;

The ship went down like lead.

Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote

Like one that hath been seven days drowned

My body lay afloat;

But swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the pilot’s boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship,

The boat spun round and round;

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I moved my lips——the pilot shrieked

And fell down in a fit;

The holy hermit raised his eyes,

And prayed where he did sit.

I took the oars: the pilot’s boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laughed loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro.

‘Ha! ha!’ quoth he, ‘full plain I see,

The devil knows how to row.’

And now, all in my own country,

I stood on the firm land!

The hermit stepped forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

‘Oh shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man!’

The hermit crossed his brow.

‘Say quick,’ quoth he, ‘I bid thee say——

What manner of man art thou?’

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woeful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale;

And then it left me free.

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns:

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

The moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door!

The wedding-guests are there:

But in the garden-bower the bride

And bridemaids singing are:

And hark the little vesper bell,

Which biddeth me to prayer!

O wedding-guest! This soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea:

So lonely ’twas, that God himself

Scarce seemed there to be.

Oh sweeter than the marriage feast,

‘Tis sweeter far to me,

To walk together to the kirk

With a goodly company!——

To walk together to the kirk,

And all together pray,

While each to his great Father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends

And youths and maidens gay!

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou wedding-guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.”

The mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the wedding-guest

Turned from the bridegroom’s door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

1798

发表回复