31 Wheat: Working in Memphis 2008

The price of wheat speeds from record to record. Trader Evan Dooley bets on the wrong direction, juggling 1 billion USD and dropping the ball. This results in a loss of 140 million USD for his employer, MF Global, in February 2008.

“I simply do not know where the money is.” —Jon Corzine, CEO of MF Global

Less than a month after Jérôme Kerviel’s catastrophic bet on European equity indices, which resulted in losses of nearly 5 billion USD to French investment bank Société Générale, another trader caused difficulties for his employer.

This time it was through speculation on wheat futures. At the end of February 2008, MF Global, one of the world’s largest futures and options brokers, had to admit that one of its traders in Memphis, Tennessee, had speculated on wheat futures with corporate accounts. Within hours, a loss of about 140 million USD occurred.

Spun out of Man Financial Group in 2007, MF Global was a commodity brokerage house that offered clearing and execution services. It had ambitions to become a financial services firm on the order of a Goldman Sachs or JPMorgan, and its CEO was Jon Corzine, former chairman of Goldman Sachs and onetime governor of New Jersey. Although it was a niche player on Wall Street, MF Global was a force on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), with 3 million futures and options positions open with a face value of more than 100 billion USD. Its customers made up almost 30 percent of the trading volume on the CME.

Trading Wheat

After corn, wheat is the second-biggest agricultural crop in the world, and it is traded worldwide on commodity futures exchanges. On the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), wheat is traded under the symbol W and the current contract month (e.g., W Z0 for wheat December 2020). One contract refers to 5,000 bushels of wheat, and each bushel is equivalent to 27.2 kilograms.

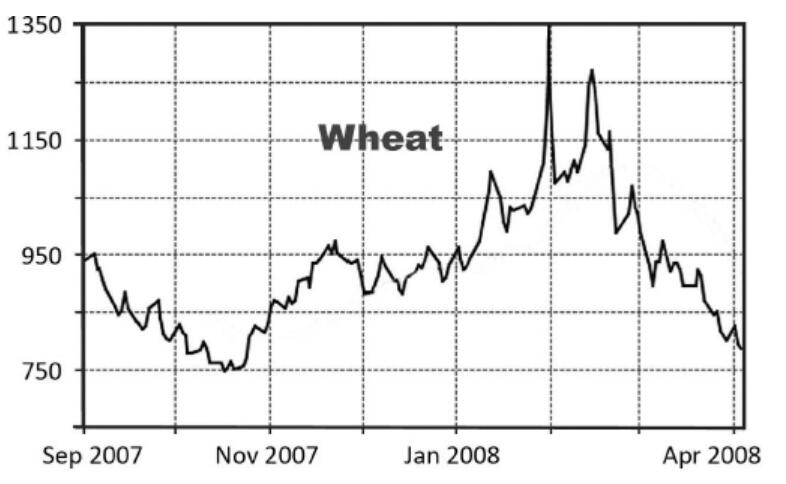

Priced at 7.50 USD per bushel in November 2007, US wheat was already trading above 8 USD by the beginning of 2008. In part this was due to a tightening supply, but the increase was also increasingly driven by speculative capital, along with a weak US currency. The price broke through 9 and 10 USD per bushel within days, and at the end of February the situation had really gotten out of hand. On February 27, wheat contracts close to delivery experienced price movements of as much as 25 percent within a day. Although trading opened positive, by noon the price had fallen to 10.80 USD.

Trader Evan Dooley speculated on falling

prices of 2 million tons of wheat.

In the afternoon, however, the price jumped again, to 13.50 USD per bushel. The news that Kazakhstan, one of the largest exporters of wheat, wanted to introduce export taxes to reduce sales was boosting the US wheat price. It was the strongest intraday price movement in wheat ever observed.

However, there was also another explanation for the price swings: Evan Dooley, who had been a trader at MF Global since November 2005, had quickly entered significant positions in wheat futures on his own account in the morning hours of February 27. With these unauthorized actions, the 40-year-old trader exceeded his limits by far.

Betting on a falling wheat price, Dooley is said to have traded around 15,000 futures—2 million metric tons of wheat. The value of the position varied between 800 million and 1 billion USD. However, as the wheat price continued to rise sharply, the company was forced to close the position with losses, that is, to buy further futures contracts. This led to a further price jump to a level that the market would not reach again, despite continuing strength, for several years.

MF Global shares lost more than 25 percent in value on that day. The losses came to approximately 140 million USD and represented four times the previous quarter. Concerned about the extent of the loss, MF Global promised to revise its internal policies and risk management. Dooley was fired immediately, and MF Global was fined 10 million USD for lack of supervision of its traders. Dooley himself was sentenced to five years in federal prison and had to make restitution of 140 million USD.

On a side note, MF Global collapsed in 2011 when the company reported a 192 million USD quarterly loss. Client funds disappeared in the aftermath, which became a huge scandal. However, the failure of MF Global, with more than 40 billion USD in assets—the eighth-biggest bankruptcy in US history—was modest compared with the chaotic 2008 failure of Lehman Brothers, which had a 691 billion USD balance sheet. Regulators were eager to show that not all Wall Street firms were too big to fail. They happily let MF Global go under.

Key Takeaways

•Less than a month after Jérôme Kerviel’s catastrophic bet on European equity indices in 2008, another trader caused trouble for his employer: Evan Dooley of MF Global speculated on falling wheat prices and built up a short position of almost 1 billion USD.

•Wheat prices kept climbing higher and higher, however, from 7.50 USD per bushel in late 2007 to more than 10 USD per bushel in January 2008.

•On February 27, 2008, the price of wheat traded in Chicago fluctuated in the course of the day by 25 percent—falling back to 10.80 USD per bushel, then jumping again to 13.50 USD in the afternoon. MF Global accumulated a loss of about 140 million USD within hours.

32 Crude Oil: Contango in Texas 2009

The price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil collapses, unsettling commodity traders around the world. A 10,000-person community in Oklahoma becomes the center of world attention. The concept of “super-contango” is born, and investment banks enter the tanker business.

“Super-Contango is a state in which a forward price of a commodity is higher than the spot price to a greater extent than can be explained by the interest and storage costs that explain the usual state of contango.” —Moneyterms.co.uk

Cushing is a small town in Oklahoma with fewer than 10,000 residents: There’s a Wal-Mart, some fast-food restaurants, and a few gas stations. Only massive tanks, pipes, and refineries hint that the town is somehow special. In the south of the city is a complex for the strategic oil reserves of the United States, with a capacity of 35 million barrels—one of the largest in the country.

Suddenly, at the beginning of 2009, Cushing—the only delivery location for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the US benchmark for crude oil—became the focus of the world’s attention. In the oil market, big-time inventory building had begun. And it began on a large scale.

Trading in Crude

Because of the many different types and qualities of crude oil, market participants have agreed to trade in a few local varieties for reference: At the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), this is US West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil, at the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) in London it’s North Sea Brent, and in Singapore the Asian reference is Tapis. Additionally, there is an OPEC basket price, which calculates the average price of seven different types of crude: Sahara Blend (Algeria), Minas (Indonesia), Bonny Light (Nigeria), Arab Light (Saudi Arabia), Dubai (United Arab Emirates), Tia Juana Light (Venezuela), and Isthmus (Mexico). On commodity futures markets, WTI and Brent are the primary references for the price of oil, which is traded in 1,000 barrels per contract under the abbreviations CL (WTI) and CO (Brent) as well as the corresponding contract months (e.g., Z9 for December 2019).

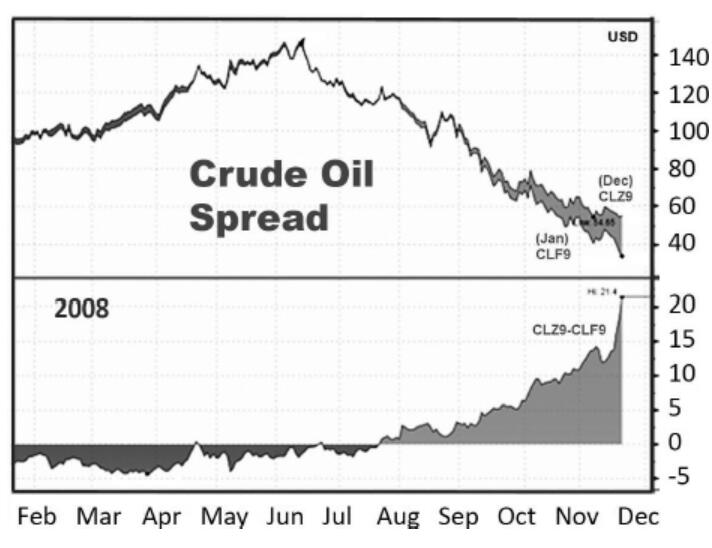

In the wake of the financial market crisis and the deteriorating economic outlook, the price of crude oil had come under massive pressure in the second half of 2008. That summer, crude oil had briefly traded at more than 145 USD for a short time. But then, the price dropped to less than 45 USD. The withdrawal of investment capital (“deleveraging”) also contributed significantly to the price decline. This became obvious through an analysis of the short-term crude oil contracts in which financial investors are typically invested, and which were now much more affected than long-term contracts.

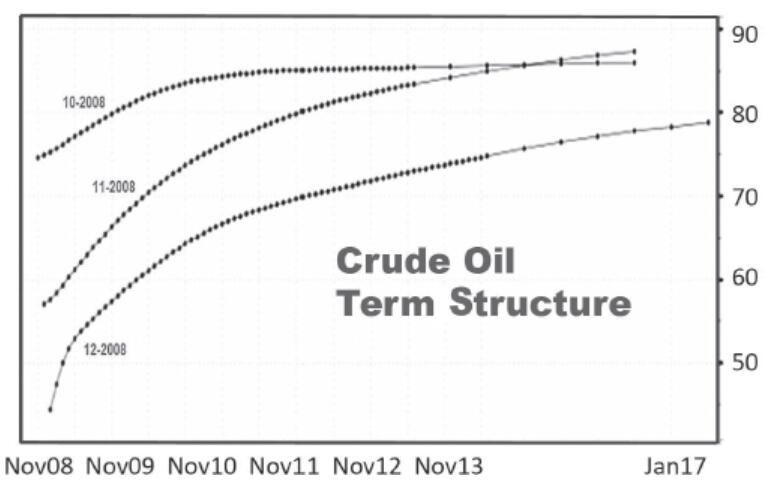

The forward term structure, which tracks the price of future crude oil deliveries over a period of several years, was still nearly flat in summer 2008, but from there, the contango structure of crude oil (WTI) increased. Contango refers to the situation in which spot prices are below the level of futures prices. This could be due to warehousing costs, including insurance and interest, for example, although those can be superseded by the effects of supply and demand.

Between October and December 2008, the contango became extreme. The price decline at the short end of WTI contracts led to a record price difference (the spread)—in excess of 20 USD—between contracts for WTI January 2009 and WTI December 2009. Commodity traders introduced the term “super-contango” to describe what was happening, and commodity analysts called the price distortion of crude oil “absurd.” WTI decoupled completely from other crude oil reference prices such as Brent and, as a barometer for international crude oil markets, was “as useful as a chocolate oven glove,” noted a commodity analyst of Barclays, the British investment bank. What led to this situation? And, more importantly, what were the implications?

Super-contango! Front-end WTI traded as low as 35 USD, while later crude contracts with later dates stayed above 50 USD.

The world’s attention turned to Cushing, the world’s “pipeline crossroads” and the only source of WTI crude oil. Contango favors stockpiling, because instead of a low current price, oil can be sold for more at a later date. The only obstacle is that the owner of the crude needs to have appropriate storage facilities. At Cushing, due to the increasing contango, the storage level of oil was steadily increasing.

In January, oil inventories counted more than 33 million barrels (1 barrel equals 159 liters), and the remaining capacity literally was disappearing like ice in sunshine. The super-contango led to “super-storage,” because every holder of crude oil futures without the appropriate capacity had to sell crude oil, if needed, regardless of price. At its low, US crude oil was trading below 35 USD.

It’s hard to know whether the super-contango was merely an expression of the short-term oversupply of the crude oil market due to the economic slowdown, or whether this was the effect of disinvestment of index and hedge fund capital in the forward contracts. In any case, the steepness of the crude oil forward curve continued to increase.

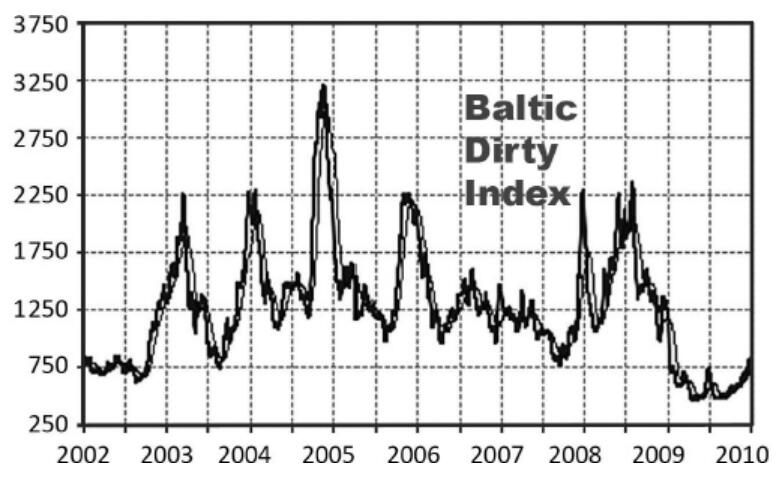

An additional factor, apart from the price differences, distinguished this situation from past events: The economic slowdown and the effects of the credit crunch had put international freight rates under extreme pressure. At the beginning of 2009, freight rates for oil tankers were around 85 percent below their highs in summer 2008.

The crude oil super-contango, combined with low freight rates, provided a lucrative business for investment banks.

For a short while early in 2009, the price difference between a current crude oil contract and a December 2009 contract exceeded 30 percent. The combination of super-contango and the low crude oil tanker freight rates opened up a new field not only for crude oil traders but also for investment banks, since it was possible to store crude oil in oil tankers on the high seas.

With sufficient inventories, it made no sense to sell oil at prices below 40 USD, if you could sell above 55 USD risk-free through a futures contract. January crude oil prices were trading 20 USD below December contracts, while the cost of storage aboard on a supertanker in January 2009 averaged around 90 US cents a barrel. Assuming that transportation, insurance, and financing were secured, there was an opportunity for immense profit for oil companies and traders.

Tanker Talk

The Baltic Exchange is a global marketplace for shipbrokers, shipowners, and charterers. The various indices of the stock exchange offer an important overview of freight rates differentiated according to cargo types, ship sizes, and shipping routes. The Baltic Clean Tanker Index tracks tankers carrying clean cargo, such as oil products (petrol, diesel, fuel oil, or kerosene); the Baltic Dirty Tanker Index is for tankers that carry cargo such as crude oil. In 2009, freight rates for bulk carriers—summarized in the Baltic Dry Index—had fallen by 94 percent since the previous summer, due to the economic slowdown and the credit crunch during the international financial crisis. In comparison, the freight rates for tankers lost a little less. Freight rates for crude oil fell by around 85 percent.

Tanker lease periods between three and nine months were particularly sought after.

In February 2009, Frontline, the world’s largest owner of supertankers, reported that 25 tankers had been chartered, and there were still open inquiries about 10 more ships. Any tanker that held less than 2 million barrels of oil was not statistically recorded, but industry experts estimated that there were as many as 80 million barrels on the water at the time, more than twice as much oil as was in official storage in Cushing. The profitable business had also taken on a new dimension. The new customers were no longer BP or Exxon, but Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Citibank, Barclays, and Deutsche Bank.

Ship brokers around the globe were surprised by the extent of storage inquiries. After all, 35 supertankers accounted for roughly 10 percent of crude oil tanker capacity worldwide. Due to additional demand, tanker freight rates recovered slightly from their lows. However, the floating inventories prevented a significant spike in oil prices during the year, despite any improvement in underlying economic data. After a nearly 75 percent drop in crude oil prices in just one year, the supply surplus of floating stock unsettled the market. For 2008, the International Energy Agency (IEA) reported a decline in oil demand for the first time since 1983.

Key Takeaways

•Cushing, a small town in Oklahoma, is the pipeline capital of the world—the only delivery point for WTI, the most important benchmark for crude oil.

•In the summer of 2008, crude oil was trading above 145 USD. But then the price collapsed to less than 45 USD, and WTI switched from backwardation into a deep contango. A super-contango was born.

•In combination with low freight rates due to the economic crisis, the oil super-contango provided a lucrative business for investment banks, which could physically buy oil, store it in supertankers, and sell it on futures exchanges, locking in a secure profit.

•The super-contango led to a massive supply glut in crude oil for a number of years.

33 Sugar: Waiting for the Monsoon 2010

A severe drought threatens India’s sugar harvest, and the world’s largest consumer becomes a net importer on the world market. Brazil, the largest exporter of sugar, has its own problems. As a result, international sugar prices rise to a 28-year high.

“The peacocks are not dancing.

It will not rain.”

—P. K. Dubey in Monsoon Wedding (2001)

June 2009 was the driest summer month in India for more than 80 years, and the dry season was nowhere near ending. In the first week of August, rainfall was only one-third of its normal level. In the main agricultural areas in the north of the country, the weather phenomenon called El Niño had practically stopped the monsoon, whose season on the subcontinent usually lasts from the beginning of June to the end of September.

One consequence of El Niño in India is significant crop failures, but India’s frequent experience of drought and famine has historically led to large storage facilities. According to the US Department of Agriculture, about 20 million metric tons of rice and about 30 million tons of wheat were stored in 2009. For sugar, however, the situation was quite different.

Crop failures were so severe, especially in the state of Uttar Pradesh, that India—the second-largest sugar producer in the world—changed from being a net exporter of the crop to becoming a net importer. After producing more than 26 million metric tons of sugar the year before, the country was initially expected to consume 22 million tons of sugar in 2009. However, in August, the Indian Ministry of Agriculture revised the harvest estimates downward, first to 17 million tons and later to 15 million tons. It was not until 2011 that the Indian authorities expected a harvest of around 25 million metric tons of sugar.

Sweet!

Almost three-quarters of the sugar produced in more than 100 countries comes from sugarcane, grown primarily in tropical and subtropical regions. Sugar beets come mainly from the European Union and Russia. Brazil, the largest sugar producer and exporter, is responsible for about 16 percent of the world’s sugar, followed by India (14 percent), China (6 percent), and the United States (5 percent). In Brazil, more than half of the sugar harvest is processed into fuel (ethanol).

Sugar is traded on multiple futures exchanges in different classifications. The most liquid trading is in Sugar No. 11 (ticker SB) on the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT), where futures contracts are traded in US cents per pound and comprise approximately 50 metric tons of sugar (112,000 pounds). Together with wheat, corn, and soybeans, sugar is the most liquid traded agricultural commodity.

In 2008, the global trading volume of sugar was about 45 million tons, which equates to almost one-third of the quantity produced worldwide. Two-thirds of total sugar production is consumed directly in producer countries and is excluded from global trade. If other trade barriers, such as quotas and trade agreements, are taken into account, only about 25 percent of the world’s sugar is available to the global market, and about 40 percent of that comes from Brazil, which has quadrupled its sugar production since the early 1990s.

With severe weather in India and Brazil, the price of sugar shot up.

Like India, Brazil also had to cope with severe weather conditions in 2009. The problem there was not drought, however, but too much water.

Over the past 40 years, the price of sugar has been very volatile. Starting with prices as low as 1 US cent per pound in 1967, the price exploded in the mid-1970s to more than 60 US cents. Then, in 2004, the price of sugar slipped below 6 US cents—levels that had not been seen for more than 20 years.

In 2010, however, there was a sugar rush! Massive imports from India and weather-related delivery delays in Brazil pushed the raw sugar price to a 28-year high. Futures contracts closed at 29.90 US cents per pound on January 29, 2010, a premium of more than 150 percent compared to the previous year. The situation calmed down only after the March contracts expired on February 26, 2010. At that point positive data from Brazil signaled that the worst scarcity was over.

Key Takeaways

•The three most important sugar producers worldwide are Brazil, India, and China, and the latter two mostly produce the crop for their own use.

•The summer of 2009 was the driest summer in India for more than 80 years. El Niño caused significant crop failures, India became a net importer of sugar on the world market, and Brazil had weather-related problems as well. The price of sugar spiked around the globe.

•Sugar prices rose to just under 30 US cents per pound by the end of January 2010—more than 150 percent over the previous year. Compared to prices in 2004, when sugar traded below 6 US cents, it represented a staggering increase of 500 percent and the highest price in almost 30 years.

34 Chocolate Finger 2010

Due to declining harvests in Côte d’Ivoire (the Ivory Coast)—the largest cocoa exporter on the world market—prices are rising on the international commodity futures markets. In the summer of 2010, cocoa trader Anthony Ward, “Chocolate Finger,” wagers more than 1 billion USD on cocoa futures.

“Of course they are people. They’re Oompa Loompas.“ —Willy Wonka in the movie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Cocoa, native to Central and South America, was considered by the Maya and the Aztecs to be a gift from the gods and therefore sacred. The seeds of the cacao tree also served as a means of payment. In the treasuries of Aztec king Moctezuma II, the Spanish conquistadors discovered, in addition to gold, more than 1,200 tons of cocoa—tax revenues and a huge currency reserve.

Today cocoa is an important cash crop, an export commodity for many developing countries, and the raw material for the production of chocolate. (In Germany, one of the countries with the highest per capita consumption of chocolate worldwide, every person eats an average of around 9 kilos per year.) Production costs for chocolate depend on the cocoa content, cocoa quality, and processing time, so that for a normal chocolate bar, the price of cocoa accounts only for about 10 percent of the cost of production.

Cocoa is traded in New York on the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT) and in London on the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE) in contracts of 10 tons each in USD and GBP, respectively.

The 10 largest cocoa producers account for more than 90 percent of the world’s crop. Côte d’Ivoire dominates global production with a market share of more than a third of world production.

In July 2010, market rumors in London suggested that the Armajaro hedge fund had placed a 1 billion USD bet in the cocoa market. Fund manager Anthony Ward was said to have bought around 240,000 tons of cocoa in an attempt to corner the market. This would have accounted for about 7 percent of global cocoa production and the majority of the available quantities. While some traders saw this as a bet that cocoa prices would continue to rise due to a declining supply, others argued that Ward was creating an artificial shortage and manipulating the market through his massive purchases just before the start of the annual cocoa harvest in October.

Where’s the Cocoa?

Cocoa’s main growing areas have shifted in recent years from Central America to Africa. The 10 largest producer countries account for more than 90 percent of the global cocoa harvest. Of these, Côte d’Ivoire is the largest supplier of cocoa in the world, with a market share of more than 33 percent. Indonesia, Ghana, Nigeria, Brazil, and Cameroon follow far behind. By 2010, however, cocoa production in Côte d’Ivoire had fallen by more than 15 percent over the previous five years, largely due to poor crop maintenance and pest infestation. Cocoa production in 2008–2009 was the smallest harvest in the previous five years, at just 1.2 million metric tons, a trend that market participants expected for the 2009–2010 crop as well.

At age 50, Anthony Ward was considered a genius in trading cocoa. His attempt to corner the market for cocoa was spectacular but not an isolated event. In 2002, Ward had purchased more than 200,000 tons of cocoa—the equivalent of 5 percent of the world’s cocoa market—through futures contracts. That was not the biggest cocoa transaction, however. The cocoa trading desk at Phibro, Salomon Smith Barney’s commodity trading business, had taken a position of 300,000 tons of cocoa in 1997. The head of the cocoa trading desk at that time? Anthony Ward.

Anthony Ward had been a cocoa trader and industry expert since 1979. In the first months of 2010, the price rose more than 20 percent because of his trades.

Anthony Ward gained his first trading experiences in 1979 with tea, rice, cocoa, and rubber. In 1998 he co-founded Armajaro with Richard Gower, initially focusing on cocoa, then adding coffee and, later, other agricultural goods. Today Armajaro manages 1.5 billion USD and, with a local presence in Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia, and Ecuador, is one of the largest cocoa suppliers to the world market. After Ward’s trades in July 2010, the British press dubbed Ward “Willy Wonka,” after the character in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and “Chocolate Finger,” in homage to a James Bond villain.

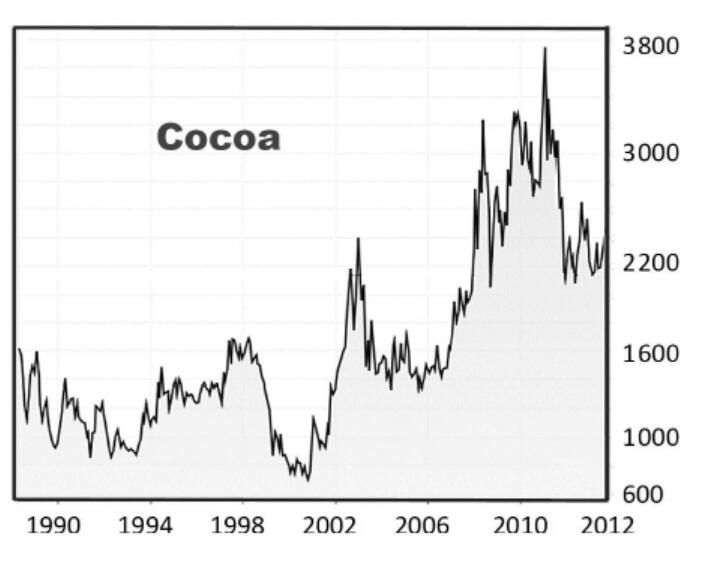

In 2009 and 2010, increasing demand, declines in production, and price speculation by hedge funds caused cocoa prices to rise more than 150 percent within two and a half years and to reach their highest level since 1977. A ton of cocoa in mid-July cost more than 3,600 USD. Because of Armajaro’s purchases, the short-term price of cocoa rose: A July contract carried a 300 USD premium compared to a December 2010 contract. Customers had to pay a premium of around 15 percent compared to a later delivery (backwardation).

In a letter to the NYSE and LIFFE, 16 companies and trading houses complained about market manipulation of the cocoa market. However, LIFFE declared that “indications for a market manipulation are not recognized.”

Key Takeaways

•The cocoa market is relatively small and highly concentrated: Côte d’Ivoire dominates global cocoa production with a market share of more than a third of world production. The 10 largest cocoa-producing countries account for more than 90 percent of the world’s crop.

•During the summer of 2010, rumors spread that hedge fund Armajaro had placed a bet of 1 billion USD in the cocoa market. Fund manager Anthony Ward, nicknamed “Willy Wonka” and “Chocolate Finger,” is said to have bought around 240,000 tons of cocoa in an attempt to corner the market.

•Compared to price levels in early 2009, cocoa prices in London and New York rose by more than 150 percent and reached their highest level since 1977. A ton of cocoa cost more than 3,600 USD in July 2010—an increase of more than 500 percent compared to 2002. It was a successful bet for Chocolate Finger.

35 Copper: King of the Congo 2010

The copper belt of the Congo is rich in natural resources, but countless despots have looted the land. Now Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC) is reaching out to Africa, and oligarchs from Kazakhstan aren’t shy about dealing with shady businessmen or the corrupt regime of President Joseph Kabila.

“The West exploited Africa and now it wants to save it. We have been living with this hypocrisy for too long. Africa can only be saved by Africans.” —Joseph Kabila, President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

“We bought an asset from the Democratic Republic of Congo that was for sale.” —Sir Richard Sykes, ENRC

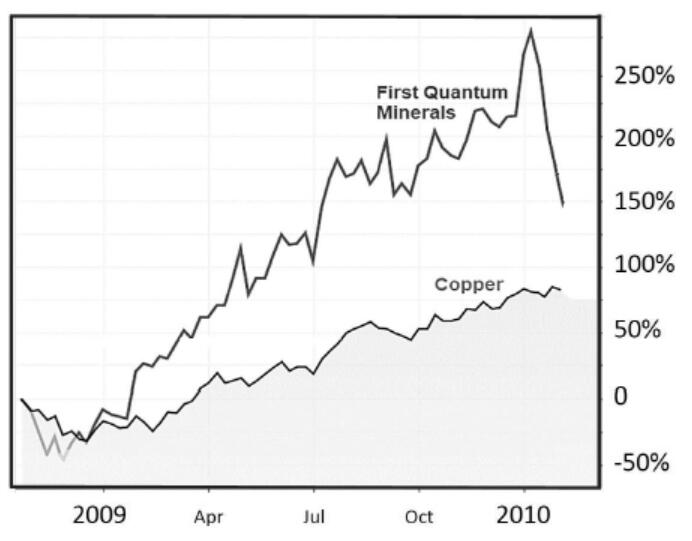

On Friday, August 20, 2010, investors in the city of London listened closely as Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC), a 12 billion USD, London-listed Kazakh mining company, took over the majority stake in Camrose Resources, which held the Kolwezi mining licenses recently expropriated by the government of the Congo. The previous owner of the extremely lucrative licenses? The Canadian mining company First Quantum Minerals. This was explosive news!

All of a sudden, after decades of colonialism, dictatorship, and warfare, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was once again the focus of media attention and the international mining industry. The Congo, one of the poorest countries in the world, nevertheless has an immense wealth of natural resources. The African copper belt stretches from the Congolese mining province of Katanga to northern Zambia. Here lies around 10 percent of the world’s copper reserves. And in 2010, copper was scarcer and more expensive than ever before: Based on its 52-week low, the price of the metal had increased that year alone by 50 percent. For the first time, copper traded above 9,000 USD per metric ton on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

An Introduction to the Congo

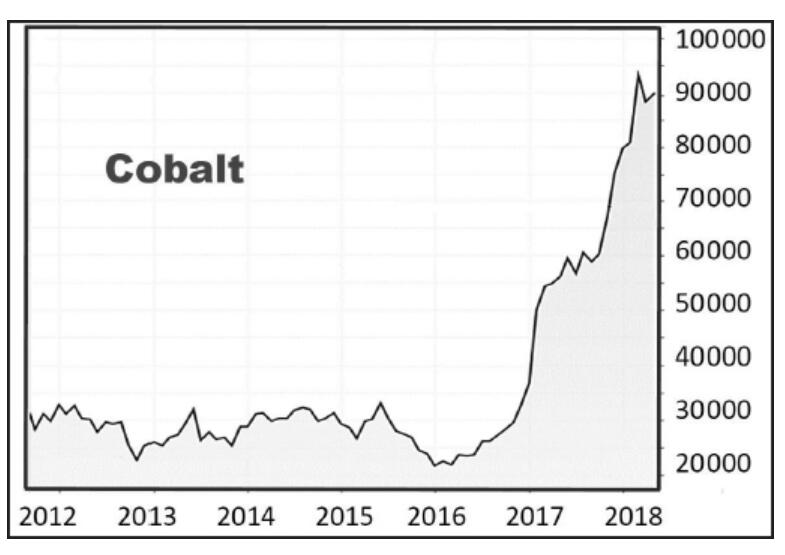

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire, is the third-largest country in Africa, after Sudan and Algeria. Neighboring countries—the (formerly French) Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Tanzania, and Angola—are all much smaller. With its wealth of natural resources, such as cobalt, diamonds, copper, gold, and other rare minerals, the Congo is a prime example of the “resource curse” thesis: The 70 million inhabitants of the Democratic Republic of the Congo are among the world’s poorest. Only Zimbabwe has a lower per capita GDP.

The Congo, whose capital is Kinshasa, gained independence from Belgium in 1960 under President Kasavubu and the popular Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. A period of instability and military intervention followed, beginning in 1965, under the long dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, during which Mobutu and the elite of the country (now called Zaire) systematically looted the wealth of the nation.

The system collapsed in 1997, when Mobutu was ousted by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. In January 2001, L.-D. Kabila was murdered by one of his bodyguards under unclear circumstances, and the presidency passed to his son, Joseph Kabila. The latter stayed in power until the end of 2018. In January 2019, opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi was declared the fifth president of Congo-Kinshasa since its independence of Belgian colonial supremacy.

Despite the official end of the second Congo war in July 2003 (the first took place in 1997–1998), conflicts still persisted in the country up until today. In the course of this “African World War,” which involved eight African states and 25 armed groups, more than 5 million people died. It was the bloodiest armed conflict since World War II.

The Kamoto Mine near the town of Kolwezi is in the heart of the Congo’s mining district, where more than 3 million tons of copper and more than 300,000 tons of cobalt are believed to be in the ground. The current market value of copper reserves alone exceeds 30 billion USD. When the mine was still in operation, the machines of state-owned mining company Gécamines, once the largest company in Africa, moved about 10,000 tons of rock each day. In September 1990, however, the central part of the mine collapsed, burying many miners. The operation came to a standstill. Under the Mobutu dictatorship, reinvestments were neglected, and the largest mines fell into decay. In the late 1990s, Gécamines sold most of its projects to international mining corporations.

Beginning in 2007, the Congolese government undertook a review of more than 60 foreign mining agreements in order to increase state involvement and ownership in the mining sector. Since then, the revision of mining licenses has created multiple sources of conflict.

The government was aiming for at least 35 percent government ownership in future mining projects. In addition, newer regulations called for a signing bonus of 1 percent of the project value, a 2.5 percent license fee on the gross income, and a stipulation that the mine would go into production within two years.

The value of the mineral reserves of the African copper belt between the DRC and Zambia exceeded the GDP of half the African continent.

In August 2009, after a 2½-year review by the government, Canadian First Quantum Minerals’ Kolwezi license was terminated. The government accused First Quantum of breaching the 2002 mining regulations, though First Quantum denied it. One of the contentious issues was the increase of the Gécamines’ share by 12.5 percent—for zero costs involved.

The situation for the Canadian company was precarious, since it had already invested more than 700 million USD in expanding Kolwezi. Moreover, after First Quantum couldn’t come to an agreement with the Kabila government, the Congolese Supreme Court also revoked the company’s licenses for the Frontier and Lonshi mines in favor of the state mining company Sodimico—another bitter blow to First Quantum.

Sly Foxes

The wealth of natural resources in the Katanga province of the Congo smoldered into a power struggle among the three craftiest businessmen on the continent: George Forrest, Billy Rautenbach, and Dan Gertler. Sixty-seven-year-old Forrest, head of the Forrest Group, had been born in the Congo and was the old man of the Congolese mining industry. In early 2004, a few months after the end of the war in the Congo, Forrest and Kinross Gold entered into a joint-venture agreement with the government over the Kamoto Copper Company (later Katanga Mining).

Rautenbach, founder of Wheels of Africa, the largest transport company in southern Africa, was a friend of Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe. He went after the jewel, Katanga Mining, through the British company Camec. However, after a short takeover battle, the Congolese government announced a review of those mining licenses, and Rautenbach took the hint. He pulled back in September 2007. Rautenbach had previously been the manager of Gécamines but was replaced by Forrest, which accounted for the hostility between the two men.

Meanwhile, Gertler was laughing on the sidelines. Just 30 years old, he closed a joint-venture contract with the government of the Congo in 2004 for the development of KOV (Kamoto-Oliveira Virgule, later the company Nikanor). KOV was the only mine in Katanga with more resources than Kamoto Copper Company. More than 6.7 million metric tons of copper and 650,000 tons of cobalt—twice as much as in Kamoto—were estimated to be in the ground. According to market prices in 2018, the value of these resources alone exceeds half the GDP of Africa.

During the takeover battle for Katanga, Gertler bought shares in that mine through Nikanor. Camec finally lost its bid at the beginning of 2008, and Nikanor and Katanga Mining merged. In addition to his financial resources, Gertler had excellent connections: He is the grandson of the founder of Israel’s diamond exchange, a friend of then-Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, and the same age as Congo president Joseph Kabila, whom he considered a close friend.

In January 2010 the newly established Highwinds Properties, owned by Dan Gertler, was awarded the Kolwezi license in a shady deal. A few months later came the bombshell. On August 20, 2010, ENRC confirmed that it had secured the licenses to Kolwezi through its 50.5 percent acquisition of Camrose Resources for 175 million USD. The company said it intended to cooperate with Cerida Global, another Dan Gertler–controlled company. With the acquisition of Camrose, ENRC was also committed to a 400 million USD loan for Highwinds and a loan guarantee of another 155 million USD for Cerida’s debts.

The Kazakh company ENRC aggressively expanded its business in Africa and was not shy about dealing with African despots like Joseph Kabila.

Camrose also offered a majority stake in its subsidiary Africo to ENRC, whose copper and cobalt projects were located near its Camec properties. This was of high strategic importance for the Kazakh company, since ENRC had acquired the Central African Mining and Exploration Company (Camec) for 955 million USD in 2009. This is where Dan Gertler came into play, as Camec was 35 percent owned by the Israeli investor, who quickly unified the three Kazakh oligarchs—Alexander Mashkevitch, Patokh Chodiev, and Alijan Ibragimov—who owned 40 percent of ENRC.

The deals between Camec and Camrose were important milestones for ENRC’s aggressive expansion policy in Africa, along with a 12 percent stake in Northam Platinum in South Africa that ENRC acquired in May 2010. Regardless of pending possible expropriations and a skeptical attitude by many institutional investors, only time would show whether ENRC would have a more favorable outcome in Congo than its Canadian rival, First Quantum.

Sometimes time flies. In November 2013, ENRC delisted its shares from the London stock exchange. The following April, an official investigation into bribery and sanction-busting began in England, and the founding partners decided to take the company private again. In February 2014, news spread that the company needed to sell all its international assets—including the copper mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—to repay debts. President Kabila, however, stayed in power until the end of 2018.

In January 2019, the opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi was declared the fifth president of Congo-Kinshasa. Leader of the opposition, Martin Fayulu, complained that Kamila, despite officially stepping down from office, would with his associates most likely continue controlling the levers of powers. Presidential elections had been due for more than two years, but elections had been postponed several times despite forceful protests. Since the end of Belgian colonial supremacy in 1960, the country had never seen a peaceful transfer of power.

Key Takeaways

•The African copper belt that runs between the Congo and Zambia holds an incredible wealth of natural resources. In 2010 it became the focus of upheaval when President Kabila revoked the mining license of Canadian firm First Quantum Minerals.

•Copper was now big business, as copper prices traded at record highs of more than 9,000 USD per ton on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

•The Kazakh (but London-listed) resource company Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC) began to massively expand its footprint in Africa. The firm’s leaders were willing to deal with shady businessmen as well as with President Kabila’s corrupt regime.

•In a murky transaction involving Dan Gertler’s Highwinds Properties, the expropriated assets of First Quantum were sold to ENRC. International investors were shocked, and the company went private a couple of years later.

36 Crude Oil: Deep Water Horizon and the Spill 2010

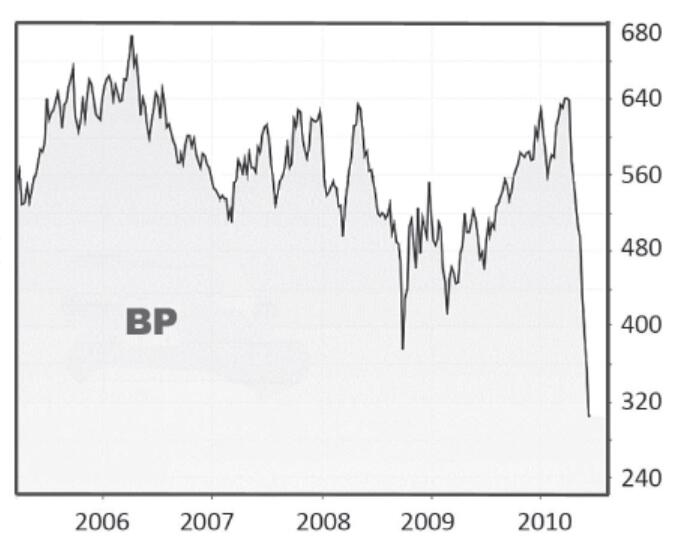

Time is pressing in the Gulf of Mexico. After a blowout at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, a catastrophe unfolds—the biggest spill of all time. About 780 million liters of crude oil flow into the sea. Within weeks BP loses half its stock-market value.

“This well did not want to be drilled . . . it just seemed like we were messing with Mother Nature.” —Daniel Barron, survivor of the Deepwater Horizon disaster

“I would like my life back.” —Tony Hayward, CEO of BP

Deepwater Horizon was one of the world’s most advanced deepwater rigs. Installed in 2001, it was 121 meters long, 78 meters wide, and 23 meters high and cost 350 million USD. In April 2010, the giant lay about 40 miles off the coast of Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico. Since February, the platform had been busy in the Mississippi Canyon Block 252, drilling in the Macondo reservoir about 4,000 meters below sea level.

April 20, 2010, promised to be a successful day, because the drill hole identified as API Well No. 60-817-44169 was about to be completed. The well would be sealed and prepared for production by a production platform. Every day counted because platform operators like Transocean charged oil companies on a daily basis. And in this case, BP was already concerned because Deepwater Horizon had been behind schedule for 43 days. The delays had already cost the big oil company more than 20 million USD.

Twenty years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill, an even bigger environmental catastrophe was looming on the horizon.

The Exxon Valdez—A Past Catastrophe

Shortly after midnight on March 24, 1989, the most severe environmental disaster in the history of the United States occurred. The 300-meter-long oil tanker Exxon Valdez was on its way from the oil-loading station of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, in the port city of Valdez, Alaska, when it collided with Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound. The accident caused a spill of almost 40,000 tons of crude oil. Around 2,000 km of coastline were contaminated, and hundreds of thousands of fish, seabirds, and marine animals died. Captain Joseph Hazelwood was drunk in his room at the time of the accident, and third officer Gregory Cousins had the bridge.

Despite an extensive cleanup, the ecosystem remains severely disturbed three decades later.

That morning, four BP managers arrived by helicopter to monitor the completion of the drilling. Only a few hours before, experts from the oil services company Halliburton had cemented the drill hole closed, but employees of Schlumberger, who were about to test the cement seal, were sent back to shore by the BP managers before they had accomplished their task.

Deepwater Horizon drilled for black gold in the Gulf of Mexico on behalf of BP.

To accelerate completion of the work, BP urged rapid replacement of the drilling mud in the well with seawater to prepare for early production. This decision precipitated an argument between BP and the Transocean managers, who considered that step premature. Unlike seawater, drilling mud holds back rising gas and oil. However, the managers of BP prevailed, and the work began.

The decision would prove disastrous. The hole had a leak, and drilling mud and gas bubbles began to spill out. The cement plug also appeared to be leaking. Work continued into the night, until suddenly a sharp hiss of methane was heard and a fountain of mud shot out of the derrick, signaling a blowout.

As the methane ignited, a huge column of flame rose into the sky. Suddenly the entire derrick was on fire, and four workers on the drilling deck were dead.

The alarm sensors designed to warn of fire and a concentration of toxic or exploding gases had been turned off to keep workers from being disturbed by false alarms in the middle of the night. Now, below deck, it was chaos. Workers, some of them barely awake and dressed in little more than a life jacket, were jumping off the platform into the water, trying to save themselves. But with the Deepwater Horizon in flames, the oil on the water’s surface had caught fire as well. Chaos also reigned in the rig’s two lifeboats.

Around 11 pm, the Damon B. Bankston, an 80-meter-long supply ship, rescued the survivors. Eleven people had died in the explosion. Two days later, the oil platform sank in the Gulf of Mexico.

The demise of the platform marked the beginning of the biggest environmental disaster in the history of the United States, an event that would provide the plot for a Hollywood blockbuster movie, starring Mark Wahlberg, in 2016.

The Macondo drilling ended in disaster. In the largest oil spill in the United States, nearly 780 million liters of crude oil ran out, and the market value of BP fell by half.

When fire broke out on the deck of the Deepwater Horizon, engineer Christopher Pleasant pressed the emergency button for the blowout preventer (BOP), a series of shut-off valves mounted directly above the well bore to interrupt the flow of oil into it. Like huge pliers, the massive shear jaw of the BOP was supposed to cap and close the well in case of disaster. The automatic emergency system was activated, but nothing happened.

A commission of inquiry later found that the Deepwater Horizon blowout preventer was poorly maintained, the hydraulic system was leaking, and the safety instructions had not been properly maintained. In addition, the ring valve of the device had been damaged weeks before. Not only was the blowout preventer in poor condition, as early as September 2009, BP had reported almost 400 defects on the rig to Transocean. However, maintenance had been delayed, and more than 26 systems were in poor condition. There were even problems with the ballast system.

After the platform sank, an oil slick formed. Approximately 1.5 km by 8 km at first, it expanded to almost 10,000 square kilometers within a few days. Between 5 and 10 million liters of crude oil were flowing out every day, and Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama all declared a state of emergency. According to the US Department of the Interior’s Flow Rate Technical Group (FRTG), the amount of oil that flowed out every 8 to 10 days matched the total amount of oil from the Exxon Valdez disaster. BP estimated that there were around 7 billion liters of crude oil in the source. Thus, it would take another two to four years until the entire amount of oil had oozed into the sea.

Shortly after the platform sank, BP initiated two independently made side-to-side relief wells (called the “bottom-kill method”), but the drilling would have taken about three months. Meanwhile, the capture of the oil with the aid of large steel domes was failing.

The depth of the seabed—around 1,500 meters—complicated the work. At the end of May 2010, several attempts were made to plug the leak with mud and cement (the “top- kill method”), but they, too, were unsuccessful. In the middle of July, BP succeeded in significantly reducing the oil flow with a new sealing attachment—a temporary closure was successful. As a result, on August 6, the leak was finally sealed permanently using a modified variant of the top-kill method (“static-kill”)—pumping in liquid cement through side relief holes. On September 19, five months after the Deepwater Horizon sank, BP declared the well “officially dead.”

It took five months to seal the oil leak.

It was estimated that nearly 5 million barrels of oil, around 780 million liters, had run out, and BP’s stock-market value fell by half in the course of the disaster. The company announced that it would divest 10 billion USD worth of assets to defer the cost of the spill.

At that point only about 3 billion USD in costs had accumulated. But BP also set up a trust fund of more than 20 billion USD for the future consequences of the catastrophe. Still unanswered is the question of who bears the responsibility for the disaster. Undoubtedly, BP took high risks, applied non-industry-compliant practices to save costs, and, as the principal, bears the financial responsibility. Transocean’s role as operator of the oil platform also needs to be clarified, especially since the platform was in relatively poor condition. For Halliburton, the questions revolve around the doubtful completion of the cement seal of the well, and initial claims have also been made to BP’s partner companies Mitsui and Anadarko.

The disaster heightened public awareness of the risks associated with deepwater drilling, both in the Gulf of Mexico and in planned projects off Brazil and Africa. As a direct result of the catastrophe, the US government passed a deep-sea moratorium, temporarily banning all new deep-sea drillings. Although this was later repealed, no new licenses have been awarded. As a further consequence, President Barack Obama fired the head of the Minerals Management Service, Elizabeth Birnbaum. The agency, now renamed the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, had grossly and negligently violated its oversight responsibilities.

It is impossible to estimate the economic consequences of the disaster, let alone the environmental consequences, which include not only the direct effects of the oil pollution but also the burning of oil and the use of toxic chemicals like Corexit, which have been used to combat the oil spill. BP said in 2018 that it would take a new charge over the Deepwater Horizon spill after again raising estimates for outstanding claims, lifting total costs to around 65 billion USD. The story of the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico will play out for decades in the future.

Key Takeaways

•At the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, the Macondo drilling, at about 4,000 meters below sea level, ended in disaster. Nearly 780 million liters of crude oil ran out, and the market value of BP, the oil and gas company in charge, fell by half within weeks.

•The oil spill caused the biggest environmental catastrophe in the history of the United States, far more devastating than the oil spill of the Exxon Valdez 20 years earlier.

•As a consequence, US authorities temporarily froze all deepwater drilling licenses. BP is estimating a price tag of more than 65 billion USD.

37 Cotton: White Gold 2011

The weather phenomenon known as La Niña causes drastic crop failures in Pakistan, China, and India due to flooding and bad weather conditions. Panic buying and hoarding drive the price of cotton to a level that has not been reached since the end of the American Civil War 150 years ago.

“It’s not something you’re going to see again in your lifetime.” —Sharon Johnson, senior cotton analyst

“I think there’s still hope for prices to go higher.” —Yu Lianmin, Chinese cotton farmer

In ancient Babylon, cotton was known as “white gold,” and the fabric has remained popular throughout history, woven by hand for hundreds of years. At the end of the 18th century, however, spinning and weaving mills began to produce fabrics and clothing at a much lower cost than could be done by hand. By the 19th century, the cotton business was booming, due to recent inventions such as the steam engine, the cotton gin, the spinning jenny, and mechanical looms.

The textile industry of the United Kingdom required ever larger quantities of the raw material, which was produced in its colonies or elsewhere abroad, especially in the southern United States, where cotton had expanded tremendously in the early 1800s. The crop thrived everywhere that was moist and warm, and labor was cheap in the American South. For about 250 years enslaved Africans had toiled on southern plantations, and cotton production grew from just 10,000 bales a year to more than 4 million until slavery was abolished after the end of the American Civil War in 1865. During that war, the price of cotton rose to dizzying heights that would only be reached again in spring 2011, almost 150 years later.

The last time cotton reached almost 2 USD per pound was after the American Civil War.

Since 1995, cotton had traded mostly between 0.40 and 0.80 USD, but at the end of September 2010, for the first time in 15 years, the price of cotton broke the 1 USD/lb level. A few months earlier, in May, the German magazine Der Spiegel had bemoaned “the end of cheap jeans,” as it noted the price explosion in cotton. But that was only the beginning. By November, cotton prices had increased another 40 percent. A sharp correction followed, but by the end of December cotton was up to 1.40 USD. And, beginning in January 2011, the market was unstoppable. The price spiked to more than 2.15 USD in March 2011—four times the level of early 2000 and a 480 percent increase over the November 2008 price.

It was the highest price ever paid for cotton since the introduction of cotton trading on the New York Cotton Exchange in 1870.

The price had actually been rising for several years. At the end of 2009, the global textile industry had forecast robust growth of around 3 percent for the following year. However, flooding and bad weather conditions in several important producer countries such as China, India, Pakistan, and Australia led to significant crop losses. Because of the falling inventory, high premiums were paid for material that was available in the short term.

Once again, severe weather conditions influenced agriculture prices.

In Pakistan, the world’s fourth-largest cotton-producing country, floods hit more than 14 million people in 2010, according to UN estimates. The exceptionally heavy monsoon season was considered the strongest in more than 80 years, and rain destroyed more than 280,000 hectares of cotton. According to the Pakistan Cotton Ginners Association, the flood destroyed 2 million bales of cotton. The All Pakistan Textile Mills Association also reported a worrying shortage of cotton. Only 30 percent of the mills had raw material in stock for the next 90 days, and Pakistan would soon stop exporting cotton.

A few weeks later, India, the second-largest cotton producer in the world, followed suit. The Indian Ministry of Textiles stopped exports, since without the ban the Indian textile industry would not have been guaranteed an adequate supply of cotton. Indian exports dropped to 0.5 million metric tons, having exceeded 1.5 million tons in the 2007–2008 season.

There were several reasons for the shortage beyond the dynamic growth of the domestic Indian textile industry. The world’s largest cotton producer and importer, China, was also enduring a shrinking cotton harvest for the second year in a row, due to low temperatures and too much rain. China Cotton Association statistics in December 2010 showed monthly imports doubling year over year.

Cotton Basics

Most cotton species and varieties are cultivated as annual plants and have high requirements for heat and water. In the Northern Hemisphere, sowing takes place from the beginning of February to the beginning of June, depending on the location.

China, India, the United States, Pakistan, Brazil, and Uzbekistan together account for around 85 percent of the world’s cotton production, with China and India producing more than half of the global market volume. In the 2009–2010 harvest, the amount of cotton grown worldwide reached 25 million metric tons.

Cotton is used mainly in textiles, accounting for about one-third of the world’s textile fibers. These can be categorized into natural fibers—such as vegetable fibers (e.g., cotton or linen) and animal fibers (e.g., wool, hair, and silk)—or artificial (synthetic) fibers. Synthetic fibers actually dominate the industry, accounting for almost 60 percent. They can be divided into cellulosic fibers (e.g., viscose) and those derived from petroleum. The most important synthetic fibers are polyester, polyamide, and polyacrylic fibers.

Cotton is traded on the commodity futures exchanges in the United States under the symbol CT and the respective contract month in a contract size of 50,000 lb per contract.

In late 2010 and early 2011, flooding and Cyclone Yasi caused severe damage in Australia, which ranked eighth among the top 10 cotton producers worldwide. The Australian Cotton Shippers Association, which had predicted a bumper harvest of more than 4 million bales, reduced its forecast by more than 10 percent.

Blocks on cotton exports worsened the situation, and panic buying and hoarding were the result.

Cotton processors in the region reacted in panic. Willing to pay any price for raw material, they pushed prices ever higher. Cotton farmers who still had inventory continued to aggravate the situation. The China National Cotton Information Center estimated that around 2 million tons of available material never reached the market in China. For example, in Huji, in Shandong province, about 220 kilometers from Beijing, growers held back more than 50 percent of their harvest at the end of January, expecting prices to continue to rise. Because of the short shelf life of cotton, that strategy could only be maintained until April or May.

In any case, the price boom in cotton was short lived. The International Cotton Advisory Committee in Washington estimated that the acreage for the 2011–2012 season would increase to 36 million hectares, the most in 17 years. It was a natural response to record prices. In the short term, however, most processors had no choice but to mix cheaper synthetic fibers with the more expensive cotton.

Key Takeaways

•If you thought that the exciting times of trading cotton took place more than 100 years ago, events in 2010 proved you wrong.

•The first impacts of global climate change were evident in a series of extreme weather events. Flooding and bad weather conditions caused by La Niña accounted for significant crop losses in several important cotton-producing countries, such as China, India, Pakistan, and Australia.

•Cotton processors in the region reacted in panic, driving prices higher. Cotton farmers who still had stocks held back their supply in expectation of even higher profits.

•As a consequence, cotton prices shot through the roof. Cotton, which once traded at 40 US cents per pound in 2009, doubled in value within a year to 80 US cents and skyrocketed to 2 USD in 2011. This was an increase of 500 percent in two years!

•Because of short supplies, export restrictions, panic buying, and hoarding, the price of cotton rose to a level not reached since the end of the American Civil War 150 years ago.

38 Glencore: A Giant Steps Into the Light (2011)

In May 2011, the world’s largest commodity trading company—a conspicuous and discreet partnership with an enigmatic history—holds an IPO. The former owners, Marc Rich and Pincus Green, have been followed by US justice authorities for more than 20 years. Without mandatory transparency or public accountability in the past, they were able to close deals with dictators and rogue states around the world.

“Glencore is Marc Rich’s legacy.” —Daniel Ammann, author of The King of Oil

“My business is my life.” —Marc Rich

It was the week before the Easter holidays in 2011, on a warm, sunny day in the banking metropolis of Frankfurt am Main, Germany. For the first time that year, temperatures climbed above 72 degrees Fahrenheit, and the city was full of people enjoying the sun’s warm rays. It was also the first week of “investor education” concerning the biggest IPO of the year, for Glencore.

Equity sector specialists were explaining corporate strategy and the business model of the world’s largest commodity trading house and the reasons why institutional investors should participate in its initial public equity offering. In a meeting room in one of the bank towers, high above the city center, 11 people nibbled on light snacks. The analyst was late, however, thanks to too many meetings and telephone conferences. And much of the information about corporate returns remained unclear. It seemed that Glencore was not being completely transparent. How exactly did the commodity giant—whose value was estimated at between 60 and 80 billion USD by the banks in the consortium and whose management team was known only to industry insiders—earn its money? Until the IPO, the Switzerland-based company had cherished one thing above all: secrecy.

Glencore (the name was derived from Global Energy Commodity Resources) was one of the world’s leading commodity players. Its business activities included the production, processing, and trading of aluminum, copper, zinc, nickel, lead, iron ore, coal, and crude oil as well as agricultural products. In terms of sales, the company was the largest in Switzerland and the largest individual shareholder, with 33 percent, of the multinational mining company Xstrata. Before the IPO, Glencore was completely owned by its management and employees, but until 1993 it had had a turbulent history determined by only one man: Marc Rich, nicknamed “The King of Oil.”

Marc Rich was the world’s most successful commodity trader. Together with Pincus Green, he broke the Seven Sisters cartel, the dominant oil companies until the 1970s.

Within commodity markets, Marc Rich was a legend. No commodity trader before or after him has ever been so successful. As a son of German-speaking Jews, Rich began his career in 1954 with Philipp Brothers, then the world’s largest commodity trader. Strong economic growth in Europe, the United States, and Asia made the 1960s a boom decade for commodity trading. But in 1973, when the company earned a record profit in which Marc Rich and Pincus Green played a decisive role, a dispute about future payments arose.

Rich and Green left Philipp Brothers and convinced Jacques Hachuel, Alexander Hackel, and John Trafford to follow them. Together they founded Marc Rich + Co AG in Zug, Switzerland, on April 3, 1974.

Rich and Green revolutionized commodity trading, breaking the multinational Seven Sisters oil companies cartel and becoming major players in international petroleum trading. In the early 1980s Rich was the world’s largest independent oil trader. Marc Rich + Co generated more profit than UBS, the biggest bank in Switzerland, and Rich’s private wealth was estimated to total more than a billion USD.

Initially, the company focused on the physical trading of iron, nonferrous metals, and minerals. Crude oil and coal marked an expansion into energy. With the acquisition of an established Dutch grain distribution company in 1982, Rich + Co also entered the agricultural sector. Through further acquisitions in mining, smelting, refineries, and processing, the company continued to grow in the 1980s and 1990s.

Who Was Marc Rich?

Marc Rich, born Marcell David Reich on December 18, 1934, in Antwerp, Belgium, was the son of German-speaking Jews. Fleeing war and persecution, the family immigrated to the United States and changed the family name to Rich. As a young man, Rich studied at New York University but left after two semesters to join Philipp Brothers in 1954, then the largest commodity trading company in the United States. He started his career under Ludwig Jesselson, and between 1964 and 1974 he worked as a manager of the Philipp Brothers offices in Spain. In 1974 Rich left the company and with Pincus Green and others founded Marc Rich + Co AG.

Within the next two decades, the new commodity trading company would become the most successful in the industry. But because of business ties to Iran—despite American political and economic sanctions and the US abolition of diplomatic relations in April 1980—Rich and Green became the focus of the US Justice Department. Accused of organized crime and tax fraud, Rich avoided prosecution by fleeing to Switzerland, where for 20 years he and Green proceeded with business as usual, while they were pursued by US justice.

After a management buyout in 1993, Rich separated from the firm, and the group was renamed Glencore. At the time, Forbes magazine estimated his private assets at more than 1.5 billion USD.

Rich never went to trial, and on his last day of office, January 20, 2001, President Bill Clinton granted full and unconditional pardons to Rich and Green in a still-controversial act.

In June 2013, Rich died of a stroke at a hospital in Lucerne, Switzerland, at the age of 78.

As it hunted for the next source of profits, the company was not picky. The list of its business partners read like a “Who’s Who” of international rogue states and dictatorships. The company traded commodities with Iran during the hostage crisis and with Fidel Castro’s Cuba, as well as with Slobodan Milosevic’s Yugoslavia, North Korea, Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, the Soviet Union under Brezhnev, South Africa’s apartheid regime, and Nigeria and Angola in the late 1970s.

In the 1990s, though, the tables turned. Pincus Green and Alexander Hackel resigned, and the press relentlessly excoriated the company’s business behavior. Finally, after heavy trading losses, Rich lost the support of other senior managers.

In November 1993, the 39 most important employees of Marc Rich + Co met at the Parkhotel in Zug to discuss the future of the company without Rich. Led by Willy Strothotte, they agreed on a management buyout, and by the following November, Rich had gradually sold his shares of the firm to management and senior employees, about 200 people in all. The value of the company—an industry leader in trading crude oil, metals, and minerals—was estimated to be between 1 and 1.5 billion USD. The new owners renamed the company Glencore, eliminating all traces of the Marc Rich name after 20 years.

Strothotte took over as chairman of the board of directors of Glencore but also moved into a top position at Schweizerischer Südelektra, which was renamed Xstrata in 1999 and was 33 percent owned by Glencore. The two companies maintained a close relationship. While Xstrata concentrated on commodity production, Glencore focused on marketing and trading raw materials. Xstrata, listed in London, offered transparency for investors. However, Glencore’s business continued to play out behind the scenes.

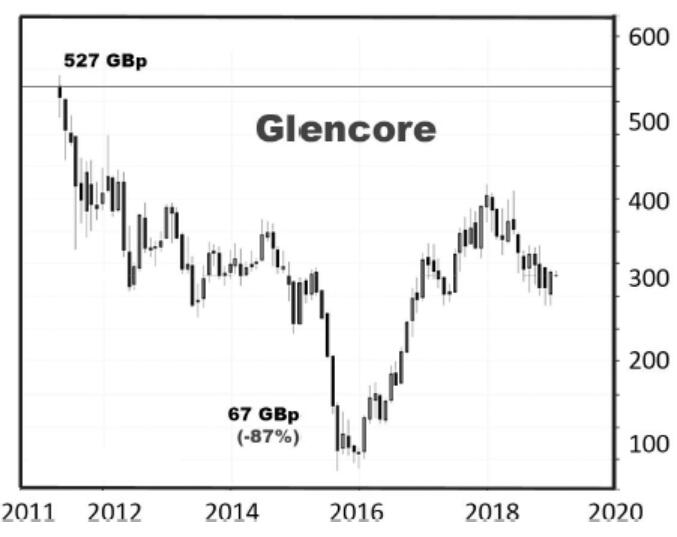

As Glencore reached the limits of growth within its corporate structure, it badly needed fresh capital, a situation exacerbated by the fact that some of the management team had to be reimbursed within the next couple of years. The initial public offering, which raised 12 billion USD, satisfied that hunger for cash. On May 19, 2011, shares of Glencore were listed for the first time in London at 5.27 GBP. In February 2012, the company announced a merger with Xstrata that would be concluded almost a year later under CEO Ivan Glasenberg. The CEO of Glencore since 2002, Glasenberg had been with the company since 1984 and, with an estimated 5 billion USD net wealth, he became one of the top 10 richest people in Switzerland.

It turned out that Glencore’s management had cashed out at the peak of the cycle: The share price of the initial IPO has never been reached again. Instead, during a commodity sell-off, shares plunged to 67 GBP on September 28, 2015, a loss of 87 percent since the IPO. In January 2019, however, Glencore’s share price had recovered to 3 GBP, which shows that its business model as a listed company was working.

Key Takeaways

•The commodity trading company Glencore had a turbulent history that, until 1993, was determined by one man—Marc Rich, nicknamed “The King of Oil.” Rich had founded Glencore’s predecessor company, Marc Rich + Co AG, in Zug, Switzerland, in 1974.

•With private wealth of more than 1 billion USD, Rich became the most famous commodity trader by breaking the Seven Sisters cartel, and by becoming the world’s largest independent oil trader. His list of business partners read like a “Who’s Who” of international rogue states and dictatorships.

•Glencore and other commodity trading companies generally maintain an aura of secrecy, since they prefer to strike their deals in private. However, to overcome financing constraints, Glencore, which was completely owned by its management and employees after 1993, raised 12 billion USD in its initial public offering in May 2011. It merged with mining giant Xstrata one year later and became a leader in both mining and commodity trading.

•In May 2011, shares of Glencore were listed for the first time in London at 5.27 GBP. In hindsight, that was the top of the cycle; during the following bear market in commodities, the shares plunged to 0.67 GBP in September 2015. Today, shares of Glencore have recovered to 3 GBP.

39 Rare Earth Mania: Neodymium, Dysprosium, and Lanthanum 2011

China squeezes the supply of rare earths, and high-tech industries in the United States, Japan, and Europe ring the alarm bell. But the Chinese monopoly can’t be broken quickly. And the resulting sharp rise in rare earth prices lures investors from around the globe.

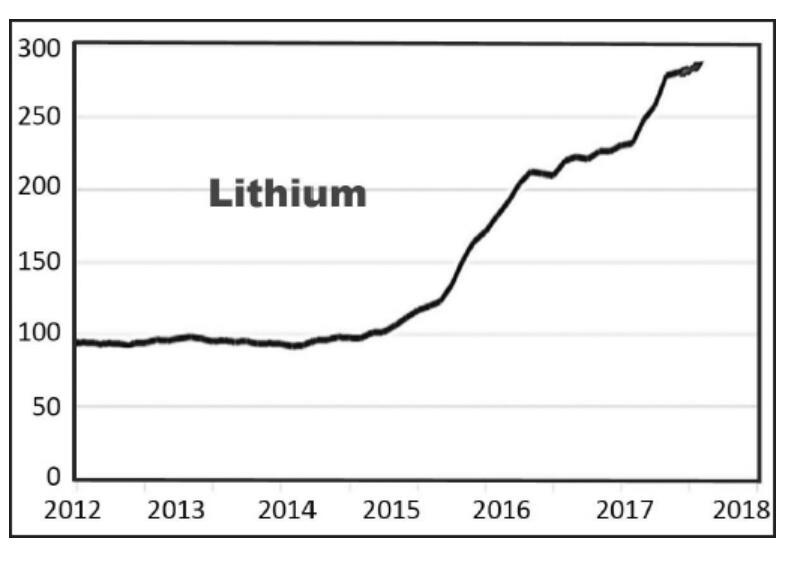

“The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths.” —Deng Xiaoping, 1992

In 2013, geologist Don Bubar bought 4,000 hectares of land in the wilderness of Canada for less than half a million USD, hoping that in a few years the area would be worth billions. Bubar and his company, Avalon Resources, planned to develop a mine for rare earths and to start production by 2015. Gold fever had seized the mining industry. Almost 300 companies worldwide were exploring for rare earths and other exotic metals like lithium, indium, or gallium. Investors were happy to spend their money on these projects, because the supply of rare earths is limited, demand was high, and prices were soaring, reflected in press headlines almost every day.

Rare earths have become indispensable for modern high-tech applications—in computers, mobile phones, or flat screens, for example, and the growth of regenerative energy can’t be achieved without rare earths in electric/hybrid cars or in wind power plants. But these metals have been at the center of a trade conflict between the main producer, China, and the industrialized countries, a situation that has been worsening over the past few years.

What Are Rare Earths?

Rare earths consist of 17 metals: scandium, yttrium, and the lanthanides group of lanthanum, cerium, dysprosium, europium, erbium, gadolinium, holmium, lutetium, neodymium, praseodymium, promethium, samarium, terbium, thulium, and ytterbium. In most deposits, light rare earths (cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, and praseodymium) are found in large quantities, while the occurrence of heavy rare earths (yttrium, terbium, and dysprosium among others) is considerably lower.

One of the most extensively used metals is neodymium, which is indispensable for the production of permanent magnets, that is, magnets that do not discharge. Neodymium is used in mobile phones and computers, wind turbines, and electric/hybrid cars. Each megawatt of power from a wind generator requires between 600 and 1,000 kg of permanent magnets made of iron-boron-neodymium alloys. Moreover, in every wind turbine, there are several hundred kilos of neodymium and dysprosium.

Lanthanum is also used in many high-tech applications. For example, about one kg of neodymium is needed for the hybrid engine of a Toyota Prius, but the batteries contain about 15 kg of lanthanum. The German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources expects the demand for rare earths to rise to 200,000 metric tons a year. At current prices, this means a market size of 2 billion USD. Compared to other metal markets, such as that for copper, with an annual production volume of almost 20 million metric tons and a market value of almost 140 billion USD, rare earths are a tiny but profitable segment.

China has dictated world market prices of rare earths, since its production accounts for about 97 percent of the global volume of 120,000 tons per year. China also has almost 40 percent of the world’s reserves, while other significant reserves are located in Russia, the United States, Australia, and India.

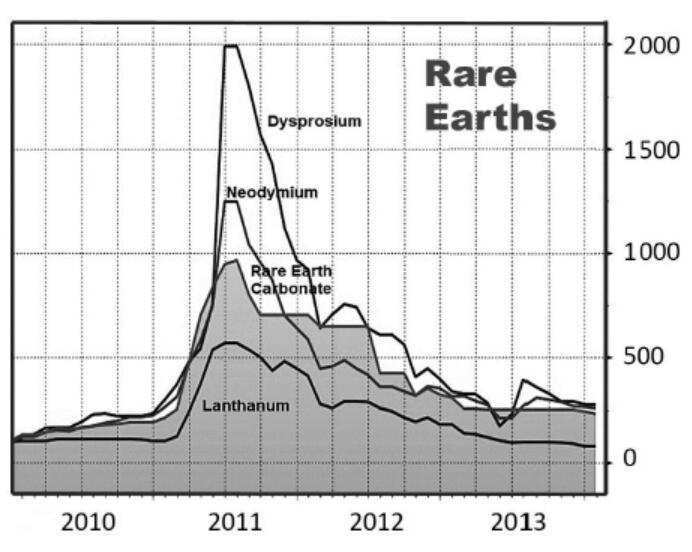

Similar to OPEC’s actions during the oil crises of the 1970s, China has been manipulating exports for years, and the United States, Japan, and Europe have all complained about export restrictions and high export duties. In 2005, exports were around 65,000 metric tons per year, but the volume has shrunk dramatically since then. As a result, prices for rare earths rose sharply from 2005 to 2008, and there was another price push in the third quarter of 2009. For the first half of 2011, the Chinese government announced exports of just 14,500 metric tons, and prices rose again. A kilogram of neodymium in May 2011 cost almost 300 USD, compared to just 40 USD 12 months earlier.

China also used its dominance in rare earth production as a political weapon. When Japan detained a Chinese ship captain, China banned rare earth exports to Japan in September 2010.

Over the past 20 years, industrialized nations have maneuvered themselves into this economic dependency. In the mid-1960s, the United States began producing rare earths in the Mountain Pass Mine, in the Mojave Desert of California. Until the late 1990s, this mine alone covered the world’s demand for these metals. Within the industry, this time period is known as the “Mountain Pass era.”

However, due to environmental constraints and low prices for rare earth metals, the mine closed in 2002. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the Chinese—able to produce the rare earths more cheaply and without worrying about environmental requirements—have begun to flood the world market.

The main Chinese production comes from Mongolia, where only a few kilometers away from the city of Baotou, with its multimillion population, is Bayan Obo, one of the world’s largest open-air mines.

It is estimated that up to 35 million metric tons of rare earths—more than half of total Chinese production—come from Bayan Obo. Another large segment of the Chinese supply derives from the southern provinces, where there are numerous small illegal projects in addition to official government mines. Production has its price, however. Processing rare earths generates large amounts of poisonous residues, which leads to heavy pollution by thorium, uranium, heavy metals, acids, and fluorides. Thus, untreated sewage has turned the nearby 12-kilometer-long drinking-water reservoir at Baotou into a waste dump enriched with chemicals and radioactive thorium.

Bayan Obo in China is the world’s largest mine for rare earth minerals.

Such heavy environmental damages are ironic, since these rare earths are indispensable to the clean energy industry, especially wind turbines and electric/hybrid cars. There’s no short-term, easy way out of the West’s self-inflicted scarcity. Development of an independent production capacity without environmental problems is a very capital-intensive undertaking. Exploration and exploitation of rare earth deposits is somewhat less problematic; despite their name, rare earths are not really scarce. Even the rarest metal in the group is around 200 times more common than gold.

Skyrocketing prices of rare earths have attracted many adventurers.

Skyrocketing prices in 2011 attracted investors and adventurers around the globe, as small mining companies began to search for rare earths and other exotic metals, and investors looked for attractive rare earth deposits to invest in. However, the majority of new rare earth deposits will never be developed or even have the slightest chance to go into production.

The two most promising companies were Molycorp and Lynas. Molycorp, which had an IPO in 2010, planned to reactivate the Mountain Pass Mine, while Lynas aimed to start production at the Mount Weld Mine in Australia in 2011. All other projects were looking at a planning horizon of at least five years. Meanwhile, the absence of a processing infrastructure was an even greater obstacle than the need for capital-intensive funding.

In 2015, Molycorp filed for bankruptcy after facing challenging competition and declining rare earth prices. The company was then reorganized as Neo Performance Materials. Lynas successfully got into production and made a first shipment of concentrate in November 2012. Today it operates a mining and concentration plant at Mount Weld and a refining facility in Kuantan, Malaysia. In September 2018, however, the processing facilities in Malaysia came under government review because of environmental concerns, and shares of Lynas began to tumble.

China will continue to be the dominant source of rare earths, which perfectly fits into the strategic plan issued by Chinese premier Li Keqiang and his cabinet in May 2015: Made in China 2025.

Key Takeaways

•The group of 17 rare earth metals, with exotic names like neodymium, dysprosium, or lanthanum, have become indispensable for modern high-tech applications like wind turbines and e-mobility.

•In 2011, China squeezed the supply of rare earths, using its dominance in rare earth production as a political weapon. Because its production accounts for more than 90 percent of global supply, China has been able to dictate world market prices.

•High-tech industries in the United States, Japan, and Europe sounded the alarm, but it was impossible to break the Chinese monopoly on the supply of rare earths in the short term. As a consequence, rare earth prices increased sharply, an average of 10 times between 2009 and 2011. Prices of neodymium and dysprosium, which are in the highest demand, increased even more drastically. This price spike attracted global investors who were eager to invest in rare earth deposits.

40 The End? Crude Oil Down the Drain 2016

A perfect storm is brewing for the oil market. There is an economic slowdown and too much storage because of contango. The world seems to be floating in oil, whose price falls to 26 USD in February 2016. But the night is always darkest before dawn, and crude oil and other commodities find their multiyear lows.

“Everybody be cool. You—be cool.” —Seth Gecko in From Dusk till Dawn

“The crude oil supply glut is gone.” —Nick Cunningham, www.oilprice.com

The Armageddon of the global financial crisis had been stopped by the massive bailouts and unconventional monetary policy of central banks around the world. As for oil, WTI crashed from almost 150 USD/barrel in June 2008 and traded temporarily below 33 USD during spring 2009. By the end of that year, crude prices had recovered to 80 USD, and between 2011 and 2014 the reference point for crude oil was 100 USD.

But in hindsight, the summer of 2014 proved to be just the quiet before a massive storm: WTI fell from almost 110 USD to less than 26 USD—a drop of 76 percent, even lower than it had been during the financial crisis. (Actually it was the lowest level for crude prices since 2003.)

Crude oil was not the only victim. The year 2016 began as an ugly one for all commodities as the Chinese domestic stock market plunged, and many other equity indices around the world followed in a case of Asian contagion. Demand in China was of fundamental importance for commodities because of demographics, growth, and the country’s immense raw material purchases. The US dollar retreated massively from highs of 100 on the Dollar Index, and raw material prices dropped further.

The massive price drop during the financial crisis had caused the term structure for crude oil to flip into contango, in which spot prices are below those of future delivery dates. It made more sense to store oil than to sell it, but the glut in supply overtaxed existing holding facilities, eventually leading to the use of supertankers as floating storage.

By the end of summer 2015, crude inventories were still rising and prices had started to crash. In early 2016, storage levels had barely declined from their 80-year highs of 490 million barrels in the United States alone, leading to pessimism about the future.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) noted that crude oil markets could “drown in over-supply” because of rising storage levels around the world. The agency said that the world had added 1 billion barrels of oil in storage in 2015, and storage levels were still rising. Even in the fourth quarter, normally when stocks are drawn down, inventories continued to climb.

Crude oil crashed because of a massive global supply glut. Oil prices fell to less than 26 USD.

There were dire warnings that the world could soon run out of storage space for oil, which would depress prices even further. Oil tumbled to its lowest level in more than 12 years, as the crude stockpiled at the delivery point for New York futures reached a record.

On February 11, 2016, when the S&P 500 index posted a 12 percent loss on the year, the Baltic Dry Index—which measures the shipping activity of dry bulk cargos around the world—fell to an all-time low of 290. The activity in commodity markets came to a halt, and the Bloomberg Commodity Index posted a 30 percent loss on the year. However, February 11 marked the lows for many assets, and the markets began to improve in the weeks and months that followed.

OPEC and Russia agreed to a joint production cut to fight the supply glut. Finally prices started to recover.

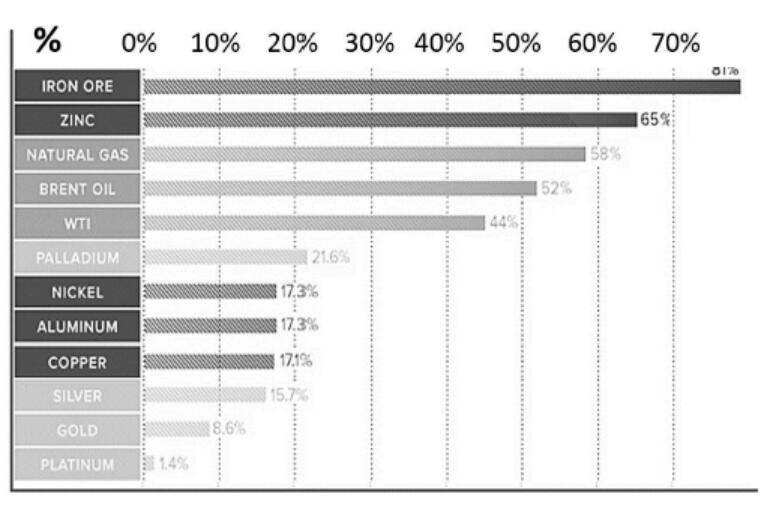

Capitulation Price Levels