您的购物车目前是空的!

Torsten Dennin《From Tulips to Bitcoins_ A History of Fortunes Made and Lost in Commodity Markets》1-15

“The Wheel of Time turns and, Ages come and pass, leaving memories that become legend. Legend fades to myth, and even myth is long forgotten when the Age that gave it birth comes again.”—Robert Jordan (1948–2007), The Wheel of Time

“Wall Street people learn nothing and forget everything [. . .] to give way to hope, fear and greed.” —Benjamin Graham (1894–1976)

Contents

Introduction

1.Tulip Mania: The Biggest Bubble in History (1637)

In the Netherlands in the 17th century, tulips become a status symbol for the prosperous new upper class. Margin trading of the flower bulbs, which are weighed in gold, turns conservative businessmen into reckless gamblers who risk their homes and fortunes. In 1637 the bubble bursts.

2.The Dojima Rice Market and the “God of Markets” (1750)

In the 18th century, futures contracts on rice are introduced at the Dojima rice market in Japan. The merchant Homma Munehisa earns the nickname “God of Markets” for his market intelligence, and he becomes the richest man in Japan.

3.The California Gold Rush (1849)

Gold Rush! Some 100,000 adventurers stream into California in 1849 alone, lured by the vision of incredible wealth. The following year, the value of gold production in California exceeds the total federal budget of the United States. Because of this treasure, California becomes the 31st state in the Union in 1850.

4.Wheat: Old Hutch Makes a Killing (1866)

The Chicago Board of Trade is established in 1848, and Benjamin Hutchinson, known as “Old Hutch,” later becomes famous by successfully cornering the wheat market. He temporarily controls the whole market and earns millions.

5.Rockefeller and Standard Oil (1870)

The US Civil War triggers one of the first oil booms. During this time, John D. Rockefeller founds the Standard Oil Company. Within a few years, through an aggressive business strategy, he dominates the oil market, from production and processing to transport and logistics.

6.Wheat: The Great Chicago Fire (1872)

The Great Chicago Fire of October 1871 leads to massive destruction in the city and leaves more than 100,000 residents homeless. The storage capacities for wheat are also significantly reduced. Trader John Lyon sees this as an opportunity to earn a fortune.

7.Crude Oil: Ari Onassis’s Midas Touch (1956)

Aristotle Onassis, an icon of high society, seems to have the Midas touch. Apparently emerging out of nowhere, he builds the world’s largest cargo and tanker fleet and earns a fortune with the construction of supertankers and the transport of crude oil. Onassis closes exclusive contracts with the royal Saudi family, and he is one of the winners in the Suez Canal conflict.

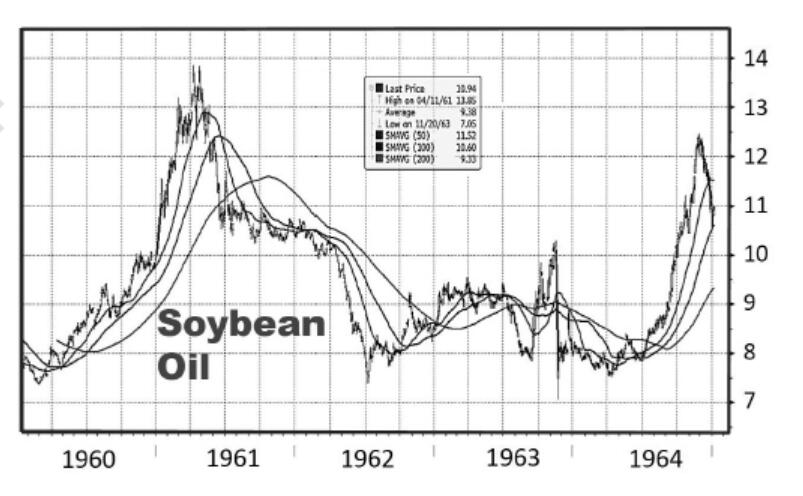

8.Soybeans: Hide and Seek in New Jersey (1963)

Soybean oil fuels the US credit crisis of 1963. The attempt to corner the market for soybeans ends in chaos, drives many firms into bankruptcy, and causes a loss of 150 million USD (1.2 billion USD in today’s prices). Among the victims are American Express, Bank of America, and Chase Manhattan.

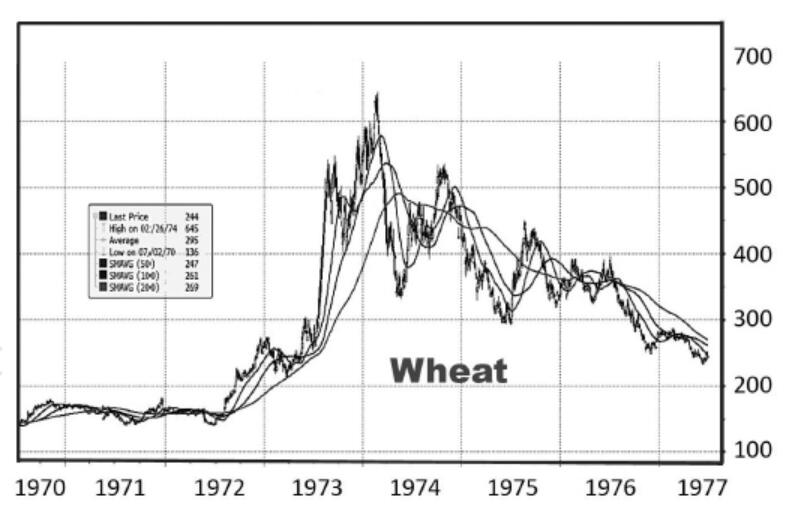

9.Wheat: The Russian Bear Is Hungry (1972)

The Soviet Union starts to buy American wheat in huge quantities, and local prices triple. Consequently, Richard Dennis establishes a groundbreaking career in commodity trading.

10.The End of the Gold Standard (1973)

Gold and silver have been recognized as legal currencies for centuries, but in the late 19th century silver gradually loses this function. Gold keeps its currency status until the fall of the Bretton Woods system in 1973. The current levels of sovereign debt are causing many investors to reconsider an investment in precious metals.

11.The 1970s—Oil Crisis! (1973 & 1979)

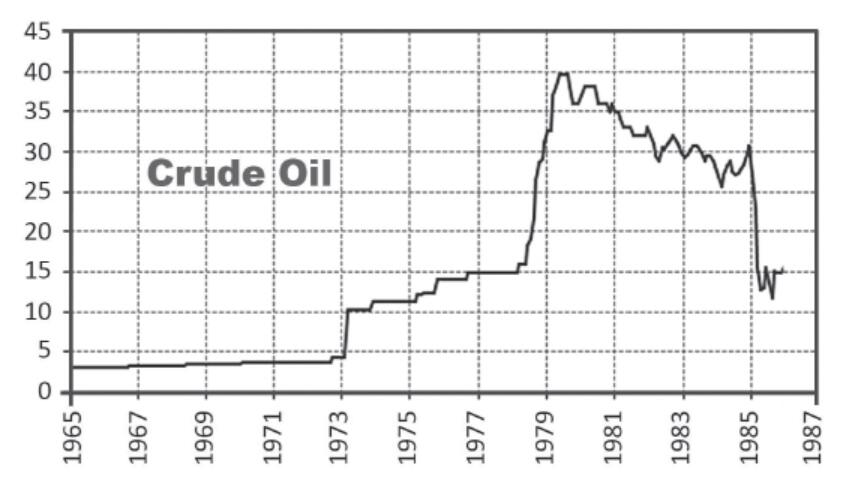

During the 1970s the world must cope with global oil crises in 1973 and 1979. The Middle East uses crude oil as a political weapon, and the industrialized nations— previously unconcerned about their rising energy addiction and the security of the supply—face economic chaos.

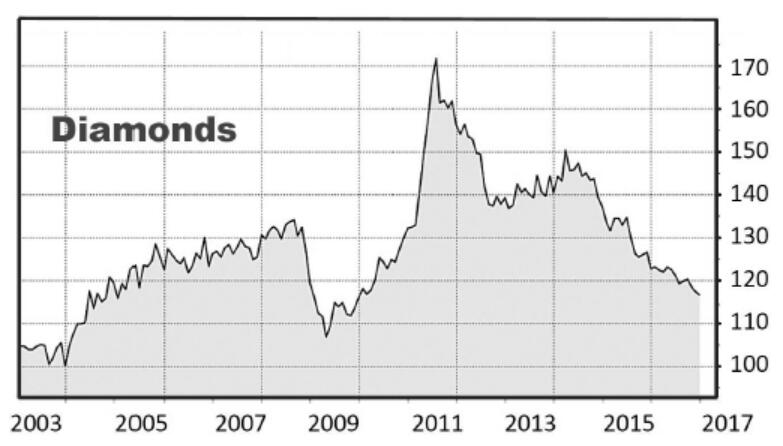

12.Diamonds: The Crash of the World’s Hardest Currency (1979)

Despite the need for individual valuation, diamonds have shown a positive and stable price trend over a long period of time. In 1979, however, monopolist De Beers loses control of the diamond market; “investment diamonds” drop by 90 percent in value.

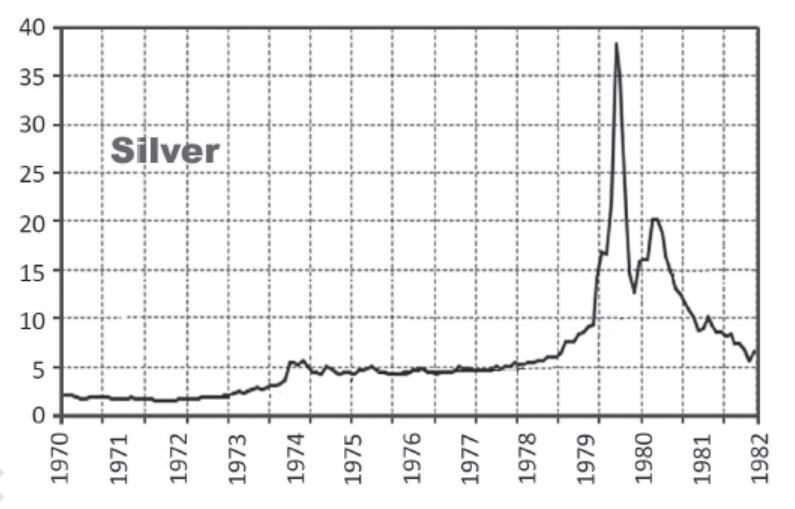

13.“Silver Thursday” and the Downfall of the Hunt Brothers (1980)

Brothers Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt try to corner the silver market in 1980 and fail in a big way. On March 27, 1980, known as “Silver Thursday,” silver loses one-third of its value in a single day.

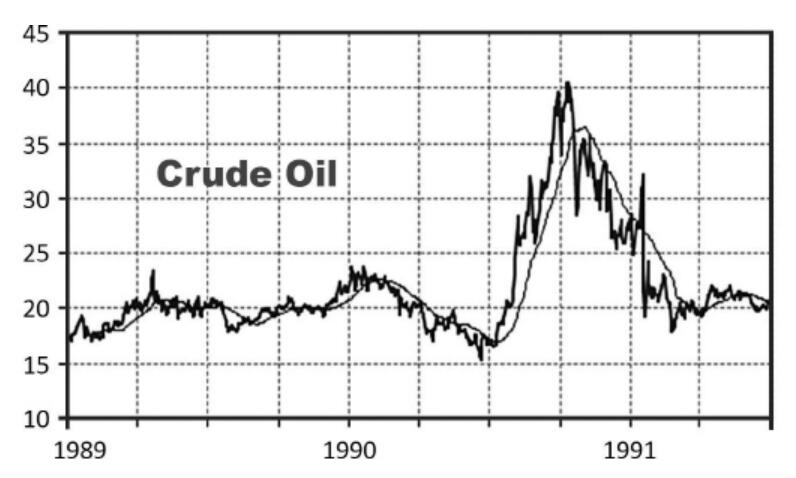

14.Crude Oil: No Blood for Oil? (1990)

Power politics in the Middle East: Kuwait is invaded by Iraq, but Iraq faces a coalition of Western countries led by the United States and has to back down. In retreat, Iraqi troops set the Kuwaiti oil fields on fire. Within three months the price of oil more than doubles, from below 20 to more than 40 USD.

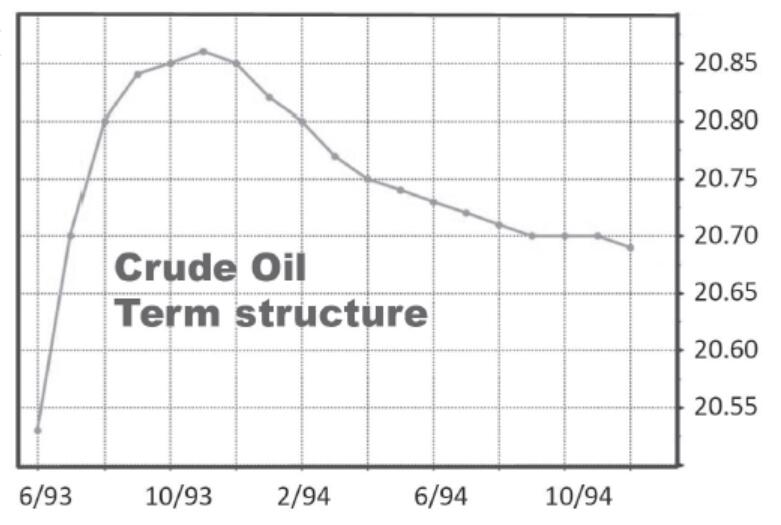

15.The Doom of German Metallgesellschaft (1993)

Crude oil futures take Metallgesellschaft to the brink of insolvency and almost lead to the largest collapse of a company in Germany since World War II. CEO Heinz Schimmelbusch is responsible for a loss of more than 1 billion USD in 1993.

16.Silver: Three Wise Kings (1994)

Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and George Soros show their interest in the silver market in the 1990s—investing in Apex Silver Mines, Pan American Silver, and physical silver. It is silver versus silver mining. Who would lead and who would lag?

17.Copper: “Mr. Five Percent” Moves the Market (1996)

The star trader of Sumitomo, Yasuo Hamanaka, lives two lives in Tokyo, manipulating the copper market and creating record earnings for his superiors but also carrying on risky private trades. In the end, Sumitomo endures a record loss of 2.6 billion USD, and Hamanaka is sentenced to eight years in prison.

18.Gold: Welcome to the Jungle (1997)

In the jungle of Borneo, Canadian firm Bre-X supposedly finds a gold deposit with a total estimated value of more than 200 billion USD. Large mining companies and Indonesian president Suharto all want a piece of the pie, but in March 1997 the discovery turns out to be the largest gold fraud of all time.

19.Palladium: More Expensive Than Gold (2001)

In 2001 palladium becomes the first of the four traded precious metals—gold, silver, platinum, and palladium—whose price breaks the psychological mark of 1,000 USD per ounce. That represents a tenfold increase in just four years. The reason lies in continuing delivery delays by the most important producer: Russia.

20.Copper: Liu Qibing Disappears Without a Trace (2005)

A trader for the Chinese State Reserve Bureau shorts 200,000 tons of copper and hopes for falling prices. However, when copper prices climb to new records, he disappears and his employer pretends never to have heard of him. What sounds like the plot of a thriller shocks metal traders all over the world.

21.Zinc: Flotsam and Jetsam (2005)

The city of New Orleans, called The Big Easy, is well known for its jazz, Mardi Gras, and Creole cuisine. Less well known, however, is that about one-quarter of the world’s zinc inventories are stored there. Hurricane Katrina’s flooding makes the metal inaccessible, and concerns over damage cause the price of zinc to rise to an all-time high.

22.Natural Gas: Brian Hunter and the Downfall of Amaranth (2006)

In the aftermath of the closure of MotherRock, an energy-based hedge fund, the bust of Amaranth Advisors shakes the financial industry, as it is the largest hedge fund failure since the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. The cause? A failed speculation in US natural gas futures. Brian Hunter, an energy trader at Amaranth, loses 6 billion USD within weeks.

23.Orange Juice: Collateral Damage (2006)

“Think big; think positive. Never show any sign of weakness. Always go for the throat. Buy low; sell high.” That’s the philosophy of Billy Ray Valentine, played by Eddie Murphy in the 1983 movie Trading Places. The film’s final showdown has Murphy and Dan Aykroyd cornering the orange juice market. In reality, the price of frozen orange juice concentrate would quadruple between 2004 and 2006 on the New York Mercantile Exchange—a consequence of a record hurricane season.

24.John Fredriksen: The Sea Wolf (2006)

John Fredriksen controls a corporate empire founded on transporting crude oil. Among the pearls of that empire is Marine Harvest, the largest fish-farming company in the world.

25.Lakshmi Mittal: Feel the Steel (2006)

The dynamic growth of the Chinese economy and its hunger for raw materials rouses the suffering steel industry from near death. Through clever takeovers and the reorganization of rundown businesses, Lakshmi Mittal rises from a small entrepreneur in India to the largest steel tycoon in the world, a position he crowns with the acquisition of his main competitor and the world’s second-largest steel producer—Arcelor.

26.Crude Oil: The Return of the “Seven Sisters” (2007)

An exclusive club of companies controls oil production and worldwide reserves. But its influence diminishes with the founding of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the rise of state oil companies outside the Western world.

27.Wheat and the “Millennium Drought” in Australia (2007)

After seven lean years for Australia’s agricultural sector, a Millennium Drought drives the price of wheat internationally from record to record. Thousands of Australian farmers expect a total failure of their harvest. Is this a preview of the effects of global climate change?

28.Natural Gas: Aftermath in Canada (2007)

The new CEO of the Bank of Montreal, Bill Downe, must report a record loss for the second quarter of 2007 due to failed commodity price speculation. Half a year after Amaranth’s bankruptcy, another natural gas trading scandal shakes market participants’ confidence.

29.Platinum: All Lights Out in South Africa (2008)

Due to ongoing supply bottlenecks of electricity from Africa’s largest energy provider, Eskom, South Africa’s major mining companies restrict their production, and the price of platinum explodes.

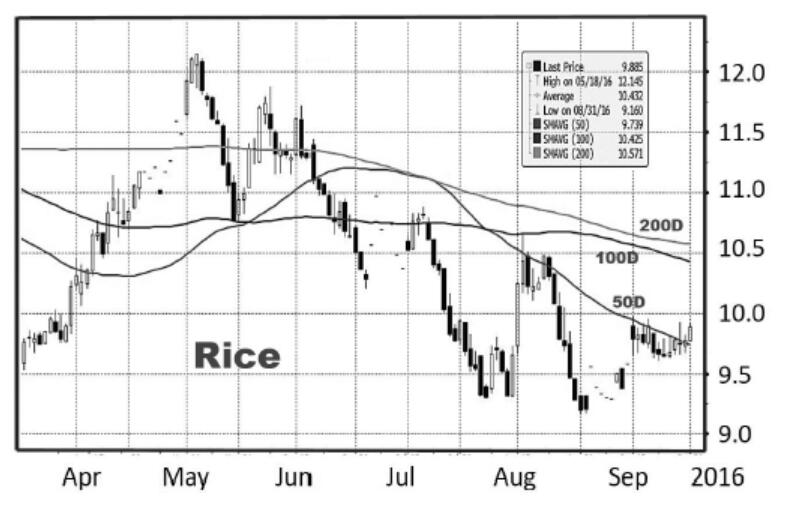

30.Rice: The Oracle (2008)

The Thai “Rice Oracle,” Vichai Sriprasert, predicts in 2007 that rice will increase in price from 300 USD to 1,000 USD, and he becomes a figure of ridicule and mockery. However, a dangerous chain reaction affecting the rice harvest is about to start in Asia and, with Cyclone Nargis, culminates in a catastrophe.

31.Wheat: Working in Memphis (2008)

The price of wheat speeds from record to record. Trader Evan Dooley bets on the wrong direction, juggling 1 billion USD and dropping the ball. This results in a loss of 140 million USD for his employer, MF Global, in February 2008.

32.Crude Oil: Contango in Texas (2009)

The price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil collapses, unsettling commodity traders around world attention. A 10,000-person community in Oklahoma becomes the center of the world. The concept of “super-contango” is born, and investment banks enter the tanker business.

33.Sugar: Waiting for the Monsoon (2010)

A severe drought threatens India’s sugar harvest, and the world’s largest consumer becomes a net importer on the world market. Brazil, the largest exporter of sugar, has its own problems. As a result, international sugar prices rise to a 28-year high.

34.Chocolate Finger (2010)

Due to declining harvests in Côte d’Ivoire (the Ivory Coast)—the largest cocoa exporter on the world market—prices are rising on the international commodity futures markets. In the summer of 2010, cocoa trader Anthony Ward, “Chocolate Finger,” wagers more than 1 billion USD on cocoa futures.

35.Copper: King of the Congo (2010)

The copper belt of the Congo is rich in natural resources, but countless despots have looted the land. Now Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC) is reaching out to Africa, and oligarchs from Kazakhstan aren’t shy about dealing with shady businessmen or the corrupt regime of President Joseph Kabila.

36.Crude Oil: Deep Water Horizon and the Spill (2010)

Time is pressing in the Gulf of Mexico. After a blowout at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, a catastrophe unfolds—the biggest oil spill of all time. About 780 million liters of crude oil flow into the sea. Within weeks BP loses half its stock-market value.

37.Cotton: White Gold (2011)

The weather phenomenon known as La Niña causes drastic crop failures in Pakistan, China, and India due to flooding and bad weather conditions. Panic buying and hoarding drive the price of cotton to a level that has not been reached since the end of the American Civil War 150 years ago.

38.Glencore: A Giant Steps into the Light (2011)

In May 2011, the world’s largest commodity trading company—a conspicuous and discreet partnership with an enigmatic history—holds an IPO. The former owners, Marc Rich and Pincus Green, have been followed by US justice authorities for more than 20 years. Without mandatory transparency or public accountability in the past, they were able to close deals with dictators and rogue states around the world.

39.Rare Earth Mania: Neodymium, Dysprosium, and Lanthanum (2011)

China squeezes the supply of rare earths, and high-tech industries in the United States, Japan, and Europe ring the alarm bell. But the Chinese monopoly can’t be broken quickly. And the resulting sharp rise in rare earth prices lures investors around the globe.

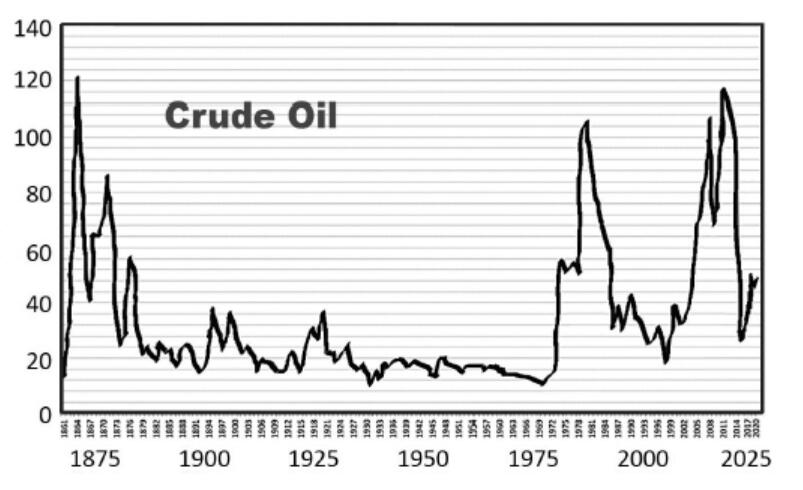

40.The End? Crude Oil Down the Drain (2016)

A perfect storm is brewing for the oil market. There is an economic slowdown and too much storage because of contango. The world seems to be floating in oil, whose price falls to 26 USD in February 2016. But the night is always darkest before dawn, and crude oil and other commodities find their multiyear lows.

41.Electrification: The Evolution of Battery Metals (2017)

Elon Musk and Tesla are setting the pace for a mega trend: electrification! Demand from automobile manufacturers, utilities, and consumers pushes lithium-based battery usage to new heights. For commodity markets, it is not only lithium and cobalt but also traditional metals like copper and nickel that are suddenly in high demand again. Electrification might prove to be the “new China” for commodity markets in the long term.

42.Crypto Craze: Bitcoins and the Emergence of Cryptocurrencies (2018)

Bitcoins, the first modern cryptocurrency, emerged in 2009. The value of bitcoins explodes in 2017 from below 1,000 to above 20,000 USD, attracting worldwide attention. This stellar price rise, followed by a crash of almost 80 percent in 2018, makes bitcoins the biggest financial bubble in history, dwarfing even the Dutch tulip mania of the 17th century. Despite the boom and bust, the future looks bright, as underlying blockchain technology reveals its potential and starts to revolutionize daily life.

Introduction

“The price of a commodity will never go to zero . . . you’re not buying a piece of paper that says you own an intangible piece of company that can go bankrupt.” —Jim Rogers

Commodities came into vogue with the beginning of the new millennium, as investing in crude oil, gold, silver, copper, wheat, corn, or sugar was introduced and marketed massively as an “investment theme” and a “new” asset class by banks and other financial intermediaries. The first investable commodity indices—the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index and the Dow Jones AIG Commodity Index—were developed in the early 1990s, but after the turn of the millennium, every major investment bank offered its own commodity index and index concept. This development opened up a new and attractive asset class for institutional investors and wealthy individuals. We witness today the same development in the cryptocurrency world, making an exotic new asset class investable for the public.

The rapid growth of the Chinese economy is the key parameter of the commodity boom, which has been evident since around the year 2000, when the “workbench of the world” developed a gigantic hunger for raw materials: Imports of iron ore, coal, copper, aluminum and zinc began soaring, and China became the dominant factor in worldwide demand. The dynamic growth of the Chinese economy catapulted commodity prices sky-high. Like a gigantic vacuum cleaner, China swept up the markets for energy, metals, and agricultural goods, and prices kept rising, since supply growth couldn’t keep up with rising demand.

At least temporarily, the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the worsening financial crisis caused a break in the skyrocketing prices. Crude oil crashed from its high at 150 USD/barrel during the summer of 2008 to below 40 USD in the spring of 2009. In the course of the year, prices recovered again, to above 80 USD. Industrial metals also benefited from the economic recovery. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, and amid worries about rising public debt as well as the stability of the financial system, the interest of investors in gold rose substantially. In 2009, with the European debt crisis looming, gold surpassed the level of 1,000 USD for the first time, but it climbed as high as 1,900 USD per troy ounce in 2011.

Exotic agricultural products such as sugar, coffee, and cocoa were also among the goods that experienced significant price increases in 2009, as the ghost of “agflation” returned and spooked markets. Market recovery after the financial market meltdown of 2008/2009 proved not to be sustainable, however. After April 2011, commodity markets entered a severe five-year bear market. A period of sluggish growth, deleveraging, and a slower economy in China worsened a massive imbalance of demand and supply for raw materials. A supply glut caused crude oil to fall back to 26 USD early in 2016. But since then, commodity markets have turned around. In 2016, for the first time in five years, they closed positive.

The Commodity Market and Cryptocurrencies—Some Basics

A commodity is any raw or primary economic good that is standardized. Organized commodity trading in the United States dates back almost 200 years, but commodity trading has a much longer history. It goes back several thousand years to ancient Sumerians, Greeks, and Romans, for example. In comparison to commodity trading, the history of the stock market—where you exchange pieces of ownership in companies—is much younger. In 1602 the Dutch East India Company officially became the world’s first publicly traded company on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in Europe. In the United States, the first major stock exchange was the New York Stock Exchange, created in 1792 on Wall Street in New York City.

Commodities can be categorized into energy, metals, agriculture, livestock, and meat. You can also differentiate between hard commodities like metals and oil, which are mined, and soft commodities that are grown, like wheat, corn, cotton, or sugar.

By far the most important commodity sector is crude oil and its products like gasoline, heating oil, jet fuel, or diesel. With the world consuming more than 100 million barrels of crude oil every day, that comes to a market value in excess of 6 billion USD per day, or 2.2 trillion USD per year! About three-quarters of crude oil goes into the transportation sector, fueling cars, trucks, planes, and ships.

Metal markets are usually divided into base and precious metals. By tonnage, iron ore is the biggest metal market, with more than 2.2 million tons of iron ore mined globally. Nearly two-thirds of global exports go to China; that’s around 1 billion metric tons! At 70 USD per ton, the market value of iron ore, on the other hand, is rather small. The biggest metal market, in value of US dollars, is gold. Around 3,500 tons are mined per year, an equivalent of 140 billion USD. The total aboveground stocks of gold are estimated at around 190,000 tons; that makes gold a physical market of nearly 8 trillion USD. In value terms, copper, aluminum, and zinc are next, whereas other precious metal markets—silver, platinum, or palladium—are rather small.

In agriculture and livestock, the biggest markets are grains like wheat and corn as well as oil seeds like soybeans, and sugar.

Bitcoins were released as the first cryptocurrency in January 2009. Since then, more than 4,000 alternative coins (“altcoins”) have been invented. The website coinmarketcap.com tracks prices of about 2,000 of them on a daily basis. After massive price corrections in 2018, the total market capitalization of all cryptocurrencies dropped below 200 billion USD. Bitcoins remain the dominant cryptocurrency, with a market capitalization of almost 70 billion USD and a market share of 40 percent. The next five most traded cryptos are ripple, ethereum, stellar, bitcoin cash, and litecoin. Together these five cryptos amount to a market capitalization of 30 billion USD, less than half of bitcoins.

Organized commodity trading by itself has a longer history than equity markets, a fact often overlooked in the focus on the dramatic price swings over the past decades. For example, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was founded in 1848 to provide a platform for trading agricultural products such as wheat and corn. But trade and the speculation in commodities is much older than that. Around 4000 BCE, Sumerians used clay tokens to fix a future time, date, and number of animals, such as goats, to be delivered, which resembles modern commodity future contracts. Peasants in ancient Greece sold future deliveries of their olives, and records from ancient Rome show that wheat was bought and sold on the basis of future delivery. Roman traders hedged the prices of North African grains to protect themselves against unexpected price increases.

The history of commodity and crypto trading is colorful and instructive, and my aim with this book is to bring to life the most important episodes from the past up to the present. Some of these are spectacular boom-and-bust stories; others are examples of successful trading. All are worth paying attention to.

The first six chapters cover major events from the 17th to the 19th century. The Dutch tulip mania of the 1600s is considered one of the first documented market crashes in history and is still a topic of university lectures. In the 18th century, rice market fortunes were earned and lost in Japan, and in the process candlestick charts—which are used today in the financial industry—were invented. In the 1800s, J. D. Rockefeller’s strategies and the rise of Standard Oil marked the beginning of the oil age. At nearly the same time in the midwestern United States, two men were trying to accumulate a fortune by manipulating wheat markets, while in California the Gold Rush broke out, with momentous consequences.

The episodes of commodity trading in the 20th century read like a “Who’s Who” of business history: Aristotle Onassis, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and George Soros are just some of the major players. Meanwhile, crude oil was playing an increasingly important role.

The 1970s saw a real boom in commodity markets. After a shortfall in its wheat harvest, the Soviet Union went shopping for US agricultural goods, reinforcing an already positive price trend in wheat, corn, and soybeans. It’s no overstatement to say that the rapid rise of crude oil prices during two oil crises in 1973 and 1979 changed the existing world order; the 1990 Gulf War was, in part, an attempt to reverse the clock. During this period the price of oil doubled. Among the collateral damage, the German conglomerate Metallgesellschaft was driven to the brink of insolvency by its crude oil-trading activities.

In the years that followed, a boom in gold, silver, and diamond prices was followed by a crash, and the Hunt brothers lost their oil-based family fortune because of the collapsing silver price. Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and George Soros later were also involved in the silver market. And in the jungles of Borneo, the biggest gold scam of all time culminated in the bankruptcy of Bre-X. Another huge speculation in 1996 was caused by the Japanese trader Hamanaka in the copper market. That was repeated almost ten years later by Chinese copper trader Liu Qibing, which also signaled the shift of economic forces from Japan to China.

The emerging commodity boom of the new millennium attracted additional speculators and led to other boom-and-bust episodes. The collapse of Amaranth Advisors, which accumulated a loss of 6 billion USD within a few weeks by betting on natural gas, hit news headlines worldwide.

Weather often has played a role. The flooding of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina led to a price spike in zinc in London, as the majority of zinc warehouses licensed by the London Metal Exchange became inaccessible. An active Atlantic hurricane season in 2006 not only caused oil prices to rise due to damage in the Gulf of Mexico but also pushed the price of orange juice concentrate to new heights.

A “millennium drought” threatened Australia, resulting in record high wheat prices worldwide. A few years later, a drought in India drove the price of sugar to levels that had not been observed for 30 years. Shortly before that, Cyclone Nargis in Asia caused a human catastrophe. Rice had to be rationed, and the rising prices led to unrest in several countries.

These fateful events often contrast with individual speculations, in which huge sums of money were involved. For example, trader Evan Dooley lost more than 100 million USD in wheat futures, just a few weeks after the loss of billions by Jérôme Kerviel, in the proprietary trading of French banking giant Société Générale, made world headlines. In 2011, the heritage of Marc Rich, “The King of Oil,” was cashed in: Glencore celebrated its initial public offering, catapulting its CEO Ivan Glasenberg into the list of the top 10 richest people in Switzerland.

As a new decade began, the trendy themes of commodity markets shifted first to rare earths like neodymium and dysprosium, then to “energy metals” like lithium and cobalt, which are essential for energy storage and the electrification of transportation in the future. Since 2009 blockchain and bitcoins have caught the attention of traders. With tradeable bitcoin futures introduced at COMEX in 2017, the cryptocurrency has now become a commodity. With prices starting the year below 1,000 USD, bitcoins rose to 20,000 USD in 2017; then the cryptocurrency crashed by 80 percent in the first weeks of 2018. In the history of the biggest financial bubbles of mankind, tulip mania was pushed to second place after 400 years at the top.

The chapters in this book are framed by the biggest and the second biggest financial bubbles in financial history: tulips and bitcoins. In between are the stories of 40 major commodity market events over four centuries. These episodes were accompanied by extreme price fluctuations and individual outcomes, and they demonstrate that each market can be subject to a boom-and-bust cycle due to a change in supply, demand, or other external factors. This holds true for South African–dominated platinum production, sudden frost in coffee or orange harvests, unrest in Côte d’Ivoire that affected the price of cocoa, strikes by Chilean mine workers that pushed copper prices up, and the fluctuation of bitcoin and other cryptocurrency prices because of financial woes.

Commodity and cryptocurrency markets are now at the crossroads of investment mega trends like demographic revolution, climate change, electrification, and digitalization. Investing in commodities, blockchain, and its applications will remain a thrilling ride.

1 Tulip Mania: The Biggest Bubble in History 1637

In the Netherlands in the 17th century, tulips become a status symbol for the prosperous new upper class. Margin trading of the flower bulbs, which are weighed in gold, turns conservative businessmen into reckless gamblers who risk their homes and fortunes. In 1637 the bubble bursts.

“Like the Great Tulip Mania in Holland in the 1600s and the dot-com mania of early 2000, markets have repeatedly disconnected from reality.” —Tony Crescenzi, Pimco

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Netherlands were on the threshold of a golden age, a period of economic and cultural prosperity that would last for about a hundred years. The country’s religious freedom attracted a great diversity of people who were persecuted elsewhere because of their faith. At this time, the small and recently founded Republic of the Seven United Netherlands was rising to the rank of world power, becoming one of the leading nations in international trade, while the rest of Europe stagnated.

As the Hanseatic League (a dominant mercantile confederation in Europe in the Middle Ages) declined in power, the young maritime nation built colonies and trading posts around the world, including New Amsterdam (today’s New York), Dutch India (Indonesia), and outposts in South America and the Caribbean, such as Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles. In 1602 merchants founded the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie—VOC), which was endowed with sovereign rights and commercial monopolies by the government. The VOC was the first multinational corporation and one of the largest trading companies of the 17th and 18th centuries. Merchants from Haarlem and Amsterdam experienced an unprecedented economic boom.

The new class of rich merchants eagerly imitated the lifestyle of noble lords and ladies by building large estates with gigantic gardens. Tulips—which had arrived in Leiden from Armenia and Turkey in the 16th century by way of Constantinople, Vienna, and Frankfurt am Main—quickly became a luxury good and a status symbol of the wealthy. Upper-class women wore the exotic flowers as hair ornaments or on their clothes for social occasions.

Tulip Mania on the Silver Screen

Tulip mania is not only an important topic in economics and finance, but it also frequently surfaces in modern pop culture. In the movie Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010), Michael Douglas explains to Shia LaBeouf what happened during the Dutch tulip mania, and a painting of tulips in his apartment is a mocking reminder of that bubble.

In 2017 Alison Owen and Harvey Weinstein produced the movie Tulip Fever, whose plot is set against the backdrop of the 17th-century tulip wars. In the movie a married noblewoman (Alicia Vikander) switches identities with her maid to escape the wealthy merchant she married, and has an affair with an artist (Dane DeHaan). She and her lover try to raise money by investing what little they have in the high-stakes tulip market.

The supply of tulip bulbs, however, grew very slowly since a bulb produced only two to three offspring every year, and the “mother” bulb actually faded away after a few seasons. Thus the supply lagged behind demand, and prices rose, opening up a lucrative niche for intermediaries. Tulips were now no longer sold by growers to wealthy clients but at auctions. And instead of occurring at organized exchanges, trading initially took place in pubs and inns. Later, groups gathered to form trading clubs, or informal exchanges, and they organized auctions according to fixed rules.

Initially the tulip bulbs were traded only during the planting season. However, as demand rose, traders sold bulbs that were still in the ground: It wasn’t the flowers that were sold anymore, but the rights to buy tulip bulbs. By this time, in the 1630s, tulip trading had become a speculative business because no one knew what the flowers would actually look like. Around 400 painters were commissioned to produce pictures that would entice potential buyers.

Tulips quickly advanced to become a status symbol. Prices skyrocketed, rising to 50 times the original level between 1634 and 1637.

Flower experts tried to satisfy their demanding clients with newer and ever more gorgeous creations characterized by particularly uniform petals and striking color patterns. The appearance of the mosaic virus, a plant infestation transmitted by aphids, actually created an extremely rare specimen, a surprising plant with flamed, two-color petals.

At the height of the boom, tulip contracts changed hands as many as 10 times. Prices skyrocketed and between 1634 and 1637 multiplied by a factor of 50. In individual cases, for example the variety Semper Augustus, buyers paid as much as 10,000 guilders for a single tulip bulb, about 20 times a craftsman’s annual salary. In January 1637 alone, prices doubled in a short period of time. An entire house in Amsterdam could be bought for just three tulip bulbs. The speculative bubble reached its climax on February 5, 1637. Traders from all over the region met in Alkmaar, and 99 tulip bulbs changed hands for 90,000 guilders, the equivalent of one million US dollars today. The excess carried the seeds of the tulip’s downfall since the crash had already begun two days earlier in Haarlem. There for the first time, at a simple pub auction, no buyer was found. The reaction spread rapidly. Suddenly all market participants wanted to sell, resulting in the collapse of the entire tulip market in the Netherlands.

In 1637, the bubble burst: Prices fell by 95 percent, and trading ceased.

On February 7, 1637, trading stopped entirely. Prices had fallen by 95 percent, and the number of open contracts referring to tulip bulbs exceeded existing bulb supply by a huge multiple. Both buyers and sellers were hoping for a solution from the Dutch government. In the end, futures trading was prohibited, and buyers and sellers were forced to agree among themselves.

Large parts of the Dutch population had been infected by tulip fever, from nobles and merchants to farmers and casual workers. Most participants, knowing nothing about the market, started their trading with the tulip bulbs and mortgaged their house or farm to increase their initial capital. However, the booming economy in the Netherlands did dampen the negative economic impact of this speculative bubble.

Dutch tulip mania is the first documented market crash in history, and the analysis of the process can be applied to the dot-com bubble of 1998–2001 or any other financial bubble. In the decades following the tulip fever, the flower changed from an upper-class status symbol to a widespread ornamental plant, which it still is today, almost 400 years later. And almost 80 percent of the world’s tulip crop still comes from the Netherlands.

Key Takeaways

•During the Dutch economic boom of the Golden Age, during the 17th century, tulips became an exclusive status symbol of the new, wealthy upper class.

•Prices skyrocketed, rising by more than 50 times between 1634 and 1637. Wide segments of the Dutch population were gripped by the speculative fever.

•Before the bust, tulip bulbs traded for as much as the value of a house in Amsterdam. Then, in February 1637, the bubble burst. Prices fell by 95 percent.

•The tulip mania is the first well-documented market crash in history. And for almost four centuries, it was known as the biggest financial bubble in history, much larger than the dot-com crash of 2000.

2 The Dojima Rice Market and the “God of Markets” 1750

In the 18th century, futures contracts on rice are introduced at the Dojima rice market in Japan. The merchant Homma Munehisa earns the nickname “God of Markets” for his market intelligence, and he becomes the richest man in Japan.

“After 60 years of working day and night I have gradually acquired a deep understanding of the movements of the rice market.” —Homma Munehisa

During Japan’s Edo period, which began in 1603, the country enjoyed its longest uninterrupted period of peace, and during this time domestic trade and the agriculture sector strengthened. The Dojima rice market was established in Osaka toward the end of the 17th century, and the city became the center of Japanese rice trading in the hundred years that followed. At the Dojima market, rice was traded for other goods, such as silk or tea. A common currency had not yet been established, but rice was generally accepted as payment (for taxes, for example).

Due to the financial needs of the country’s feudal lords, warehouses started to accept warrants, which promised future delivery instead of the actual goods, and many landowners pledged their harvests for years in advance. Soon trading warrants were uncoupled from trades of physical rice at Dojima; a lively trade in so-called rice coupons evolved. Over time the rice coupons surpassed rice production levels by far. In the middle of the 18th century, almost four times the quantity of rice produced was traded in rice coupons.

In 1749 around 100,000 bales of rice were traded in Osaka, but at the same time, there were only about 30,000 physical bales of rice in Japan.

What Is a Rice Coupon?

Rice coupons are a standardized form of a promise for the future delivery of rice, in which the price, quantity, and delivery date are fixed. If the market price is above the agreed price, the buyer makes a profit. If the price of rice is lower than the contract price, the buyer suffers a loss. Rice coupons are the first known standardized commodity futures in the world, and the Dojima rice market can be regarded as the first modern futures exchange, predating the introduction of trading in Amsterdam, London, New York, and Chicago.

In 1750, at the age of 36, Homma Munehisa took over his family’s rice-trading company. As the owner of large rice fields in the northwest of Japan, Homma specialized in grain trading. At first he concentrated his activities in Sakata, where his family was located. Later he moved to Osaka.

There Homma began to trade rice coupons, and in order to be informed as quickly as possible about the actual harvest in Sakata, he built up his own communication system, which covered about 600 kilometers. His family’s rice fields offered him valuable insider information. But in addition, Homma was probably the first to use analyses of historic price movements. He invented a graph, later known as a candlestick chart, that is still in use today. In contrast to a line chart, the “candles” not only show the opening and closing prices in the course of a day but also track the intraday high and low prices. Homma was convinced that by analyzing historic price movements, it was possible to recognize repetitive patterns that would allow him to make a profit.

The following episode is legendary: Over several days Homma, who seemed to have more background information than his competitors, bought more and more rice from local farmers at the rice exchange in Dojima. Again and again he drew a paper out of his pocket and peered at symbols that remotely looked like candles. On the fourth day, a messenger from the countryside arrived in Osaka with reports of harvest losses because of a storm. The price for rice in Dojima jumped up, but there was hardly any rice for sale.

In just a few days Homma had gotten control of Japan’s entire rice market, and he became rich beyond description. After his success at the Dojima exchange, Homma moved to Edo (Tokyo) and continued his ascent, acquiring the nickname “God of Markets.” Raised to the aristocracy, he served as a financial advisor to the Japanese government. He died in 1803. It was almost 200 years before his invention, the candlestick chart, was rediscovered and popularized by investors and traders alike.

Key Takeaways

•The trader Homma Munehisa cornered the Japanese rice market in 1750, buying physical supplies of rice and acquiring rice coupons on the basis of his superior market intelligence.

•Earning the nickname “God of Markets,” he became the richest man in the country.

•Homma invented candlestick charts, which are still used today in financial and technical analysis.

3 The California Gold Rush 1849

Gold Rush! Some 100,000 adventurers stream into California in 1849 alone, lured by the vision of incredible wealth. The following year, the value of gold production in California exceeds the total federal budget of the United States. Because of this treasure, California becomes the 31st state in the Union in 1850.

“Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” —Samuel Brannan

It’s hard to imagine today, but before 1848 California was an inhospitable and remote place, populated mainly by Mexicans, descendants of Spaniards, and Native Americans. Among the few European settlers was the Swiss-German émigré John Augustus Sutter, who had left his wife and children in Switzerland after the bankruptcy of his company and moved to the American West. By this time he owned a large piece of land in the Sacramento Valley, a settlement he called Nueva Helvetica. Sutter built a fort at the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers, and on the southern arm of the American River, near the village of Coloma, he started to put up a sawmill. It was there, on the morning of January 24, 1848, that one of the workers, carpenter James Wilson Marshall, found a gold nugget in the riverbed. Sutter and Marshall tried to keep the find secret while they gradually bought up more land. But the news of the spectacular discovery couldn’t be concealed for long when Sutter’s employees began to pay for goods with the gold they had found.

Things soon got out of control. Samuel Brannan, a Coloma shopkeeper, filled a bottle with gold nuggets and traveled to San Francisco. There he rode through the streets, waving the bottle and shouting, “Gold, gold from the American River,” to gain attention for his business, which just happened to include prospecting equipment. The California Gold Rush was on.

In 1848 only 6,000 people came to search for gold. But the following year gold fever truly took hold. As news of the finds spread, adventurers from all over the world hurried to California. Almost 100,000 people traveled to California in search of wealth and fast fortune in the boom year of 1849. They came from Asia as well. More and more Chinese arrived at Gum San, the “mountain of gold,” as they called California.

The numbers are staggering. In 1848 California had fewer than 15,000 people. In 1852, four years after the first gold discovery, the population exploded tenfold. San Francisco grew from fewer than 1,000 inhabitants in 1848 to about 25,000 residents in 1850. By 1855 more than 300,000 adventurers were searching for gold, and there were plenty of merchants to service—and take advantage of—them.

The Gold Rush in the Movies

With No Country for Old Men, directed by the Coen brothers, and The Hateful Eight, by Quentin Tarantino, recent years have seen a comeback of the Western as a movie genre. The concept of a gold rush was a popular theme in these movies in the past. Perhaps the most prominent is The Gold Rush (1925), a classic silent movie with Charlie Chaplin in his Little Tramp persona participating in the Klondike Gold Rush. Re-released in 1942, the movie remains one of Chaplin’s most celebrated works. More recent is Gold, made in 2013 by Thomas Arslan: The plot focuses on a small group of German compatriots who head into the hostile northern interior of British Columbia in the summer of 1898, at the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, in search of the precious metal.

Prices for prospecting gear multiplied by 10. In Coloma, Sam Brannan’s business took in 150,000 USD per month. Still, the promise of great wealth kept miners panning for gold in the riverbeds. Success meant they’d earn about 20 times as much as a worker on the East Coast in one day. In many cases six months of hard work in the goldfields earned adventurers the equivalent of six years of “normal” work. Annual gold production in California rose to 77 tons in 1851.

The value of that amount of gold exceeded the total US gross domestic product at that time. Many miners, though, had a hard time holding on to their earnings. Far from civilization, merchants charged fantastic prices for their goods, while saloonkeepers profited greatly on alcohol and gambling. In truth, the actual winners of the gold rush were businessmen and merchants like Samuel Brannan. The most famous of these is probably entrepreneur Levi Strauss. Born in Germany, he set up shop in San Francisco, and when he realized prospectors needed sturdy trousers to work in, he trimmed tent fabric to meet the demand. Jeans were born.

Almost 100,000 people came to California in 1849 alone. By 1855 there would be more than 300,000 new migrants.

With its growth in wealth and population, California’s political weight also increased. In 1850 the “Golden State” was incorporated into the United States. The boom didn’t last forever, though. Around 1860 the easily accessible gold reserves had been depleted, and many cities were abandoned. The population of Columbia, founded just 10 years earlier, dropped from 20,000 people to 500. Boom towns became ghost towns.

The pattern of the California Gold Rush would be repeated in other places over the next half century. Within a decade, the population of Australia multiplied by 10 in the aftermath of the 1851 gold rush on that continent, which evolved from a British convict colony to a more or less civilized state. In 1886 gold was found on the Witwatersrand south of Pretoria in Transvaal, South Africa. In a few years, Transvaal became the largest gold producer in the world. And in 1896, gold was discovered on the Klondike River in Alaska, leading to boom towns such as Dawson City at the confluence of the Klondike and the Yukon Rivers, which grew from 500 to 30,000 inhabitants within two years.

As for California, Sutter’s settlement eventually developed into Sacramento, the capital of the state. The huge wave of 19th-century gold seekers is recalled in the name of San Francisco’s football team—the 49ers. And what about John Augustus Sutter? He died in poverty in 1880.

Key Takeaways

•The discovery of gold by Swiss-German immigrant John Augustus Sutter and James Wilson Marshall triggered a true global gold rush. More than the prospectors, however, it was the merchants who generally became rich selling equipment and services.

•The California Gold Rush of 1849 kicked off a huge wave of immigration—with 100,000 new arrivals in that year alone.

•The discovery of gold accelerated California’s development, leading to statehood in 1850.

•The pattern of gold rush booms was followed in Australia, South Africa, and the Yukon.

4 Wheat: Old Hutch Makes a Killing 1866

The Chicago Board of Trade is established in 1848, and Benjamin Hutchinson, known as “Old Hutch,” later becomes famous by successfully cornering the wheat market. He temporarily controls the whole market and earns millions.

“Did you hear what Charlie said? Charlie said we were philanthropists! Why bless my buttons, we’re gamblers! . . . You’re a gambler! and I’m a gambler!” —Benjamin Hutchinson

ACorner in Wheat is a short silent American film, made in 1909, that tells of a greedy tycoon who tries to corner the world market on wheat, destroying the lives of the people who can no longer afford to buy bread. The classic movie, set in the wheat-speculation trading pits of the Chicago Board of Trade building, was adapted from a novel and a short story by Frank Norris, titled The Pit and “A Deal in Wheat,” respectively. In 1994 A Corner in Wheat was selected for preservation in the US National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Chicago had become the hub for agricultural products in the American Midwest in the 19th century, as large quantities of grains entered the city and more and more warehouses were built to better coordinate supply and demand. Prices regularly came under pressure, and in 1848 the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) was founded.

Benjamin Peters Hutchinson, nicknamed “Old Hutch,” is famous for being the first person to corner the wheat market. Born in Massachusetts in 1829, he moved to Chicago at the age of 30, started trading in grain, and became a member of the CBOT.

In 1866 Hutchinson was betting on a poor wheat harvest. From May to June of that year, he grew his position, both in the spot market and in futures contracts. His average realized price was reported to be 88 US cents per bushel. Then, in August, the price began to rise steadily because of below-average harvests in Illinois, Iowa, and other states that delivered grain to Chicago. On August 4, the price of wheat ranged between 90 and 92 US cents per bushel. Short sellers soon realized that there would not be enough wheat to meet their delivery obligations. (The strategy of short sellers is to sell contracts at the beginning of the season; they assume that prices during harvest season will come under pressure, and they’ll be able to close their positions with a profit.)

By August 18, Hutchinson’s control of the tight physical market had driven wheat prices up to 1.87 USD. He had become a rich man. As a consequence, however, the CBOT declared illegal the practice of acquiring futures contracts and trying to prevent physical delivery at the same time.

What Is a Commodity Futures Exchange?

The Chicago Board of Trade, established in 1848, is one of the oldest organized commodity futures exchanges in the world. The function of every futures exchange is to provide liquidity and a central marketplace for buyers and sellers to handle standardized contracts (futures and options) that are subject to physical delivery in the future. At the CBOT, these are mainly agricultural products such as wheat, corn, or pork bellies. In 1864 the CBOT introduced the first standardized exchange-traded futures contracts. In 2007 the CBOT and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) merged into the CME Group. Ten years later, the CME introduced bitcoin futures in the commodity segment of the exchange.

In 1888 Hutchinson saw another opportunity for lucrative speculation. During the spring, he bought wheat in the spot market and acquired more and more futures contracts for maturity and delivery in September. The storage capacity in the city was around 15 million bushels, and Hutchinson controlled most of the wheat available in Chicago through the spot market.

On September 22 the wheat price broke the psychological level of 1 USD.

As a few years before, his average realized price was below 90 US cents per bushel. But this time Old Hutch was facing a powerful group of short sellers who included John Cudahy, Edwin Pardridge, and Nat Jones; they would challenge him over future deliveries in September.

Until August, the price of wheat remained at around 90 US cents per bushel. But Old Hutch again had the right instincts. Frost destroyed a large part of the local crop. And European demand for wheat imports also grew because of an unexpectedly large crop deficit. The price started to rise, and on September 22 it broke the psychologically important mark of 1 USD.

One day before maturity of the futures contracts, prices climbed to 1.50 USD. Hutchinson set the final settlement price at 2 USD.

On September 27, three days before the contracts for September expired, wheat prices rose to 1.05 USD, then increased further to 1.28 USD. Market participants caught on the wrong side began to panic, and short sellers were forced to cover their positions in what’s known as a “short squeeze.” With his positions in the physical market, Old Hutch controlled the price. The day before maturity, on September 29, he offered 1.50 USD to the big short sellers and raised the settlement price to 2 USD. Based on his average realized price, Hutchinson must have realized a profit of around 1.5 million USD.

He wasn’t done speculating, however. Within the next three years, Hutchinson had given up his profit. Later he lost his entire fortune.

Key Takeaways

•Benjamin Peters Hutchinson, nicknamed “Old Hutch,” was a grain trader who bought wheat on the spot market and acquired contracts for future delivery at the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). By cornering the wheat market in Chicago in 1866 and 1888, he was able to double his investments within weeks, earning a fortune.

•The CBOT was established in 1848 and is today one of the oldest organized commodity futures exchanges in the world. The exchange later declared illegal the practice of cornering a market by buying harvests physically and financially at the same time.

•The CBOT and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) merged in 2007 to become the CME Group.

5 Rockefeller and Standard Oil 1870

The US Civil War triggers one of the first oil booms. During this time, John D. Rockefeller founds the Standard Oil Company. Within a few years, through an aggressive business strategy, he dominates the oil market, from production and processing to transport and logistics.

“Competition is a sin.” —John D. Rockefeller

The production of petroleum from coal or crude oil as an inexpensive alternative to whale oil for lamp fuel is commonly regarded as the beginning of the modern petroleum industry. On August 27, 1859, Colonel Edwin Drake discovered a lucrative deposit of crude oil near Titusville, Pennsylvania. The onset of the American Civil War two years later sparked the first oil boom in that state. The price of oil rose to more than 100 USD per barrel (measured in today’s prices). Drilling rigs soon spread across farms in northwestern Pennsylvania, as hundreds of small refineries were created near the oil wells and along the transport routes to Pittsburgh and Cleveland, Ohio, cities that were home to major railroad crossroads: The New York Central and Erie Railroad led to Cleveland, while Pittsburgh served as an important east-west junction on the Pennsylvania Railroad. The majority of freight on these railways still consisted of grains and industrial goods, but the volume of oil products was growing rapidly.

In 1863 John Davison Rockefeller, age 24, founded a small oil refinery in Cleveland together with his brother William. The son of penniless German immigrants, John worked as a dishwasher during his school years and graduated as an accountant. Rockefeller’s company was successful and prospered, despite fluctuations in the market. The oil boom had led to a spike in production, and the price of the commodity fell from 20 USD per barrel in 1861 to only 10 US cents. In 1866, one year after the end of Civil War, however, the price had risen again to more than 1.50 USD.

With William, Rockefeller founded a second refinery in 1866, then, in 1870, he reorganized his company, naming it the Standard Oil Company. A year later, Rockefeller and other refinery owners formed an alliance to obtain discounts from railway operators. In addition, this alliance was responsible for railway operators raising prices for competitors, which led to an oil war in 1872.

At the end of that year, Rockefeller took over the presidency of the National Refiners Association, which represented 80 percent of all American refineries. He would continue to aggressively grow Standard Oil, and by 1873 he had managed to acquire or to control almost all refineries in Pennsylvania.

From Crude Oil to the Plastic-Wrapped Cucumber at Your Supermarket

A refinery splits crude oil into its various components, such as light and heavy fuel oil, kerosene, and gasoline. With additional steps, a variety of alkanes and alkenes can also be produced from petroleum. Petroleum remained the most important use of crude oil until the rapid spread of automobiles in the 1920s. Although Henry Ford had intended ethanol to fuel his cars, the Rockefeller family, as founders of the Standard Oil Company, pushed for gasoline to power automobiles and succeeded.

Today, oil is still by far the most important source of energy, at the core of every industrial society, and the base for numerous chemical products, such as fertilizers, plastics, and paints. Although three-quarters of crude oil production is used in transportation, it will take e-mobility further decades at least to challenge the supremacy of crude oil.

Between 1875 and 1878, Rockefeller traveled throughout America to convince the owners of the 15 largest refineries to become part of his Standard Oil Company. Smaller companies had to follow suit or perish: For example, the plant of the Vacuum Oil Company, founded in 1866, went up in flames. Other entrepreneurs sold Rockefeller their companies for well below half of their market value. As early as 1882, Standard Oil controlled more than 90 percent of the refinery business in the United States.

Next, the company turned to pipeline and distribution networks. Rockefeller built his own sales channels, forcing other trading networks out of the market. In late 1882, the National Petroleum Exchange opened in New York to facilitate the trading of oil futures.

In the end, Standard Oil had a hold over virtually the whole crude oil value chain in the United States—from oil production to processing, transport, and logistics—and began to extend its dominance to the global oil market as well.

Accumulating a fortune of around 900 million USD by 1913, Rockefeller represented the American Dream, the richest man of all time.

By transforming his enterprise, Rockefeller was able to postpone the destruction of his empire. But his aggressive company strategy eventually prompted the first antimonopoly legislation in the United States. In 1911, the Supreme Court ordered the dismantling of Standard Oil. As a result, the company’s share price fell like a stone. Rockefeller, nevertheless, was able to buy back large quantities of the stock, which only increased his fortune in the years that followed. World War I, increasing motorization, and advances in the industrialization process all resulted in a rapid increase in the demand for oil.

Eventually Standard Oil was broken up into 34 individual companies, from which today’s ExxonMobil and Chevron have emerged. Other sections of the original firm were liquidated over time or were absorbed by other oil and gas companies.

Back in 1913, the total wealth of John D. Rockefeller was estimated at 900 million USD, the equivalent of 300 billion USD today. This is more than twice the private wealth of Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon and, according to Forbes, the wealthiest man in the world today (before his divorce).

The son of John D. Rockefeller, Nelson, almost became president of the United States, but instead served as vice president from 1974 to 1977. David Rockefeller, the last grandson of John D. Rockefeller, died in 2017. Even today, the name Rockefeller is a symbol of vast wealth and also of philanthropy.

Key Takeaways

•The American Civil War fueled the first crude oil boom in history. Prices in 1861 soared above 100 USD (in today’s currency).

•John D. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company, a corporation that not only came to control the US market for crude oil but also dominated the global market.

•The rise of the automotive industry and industrialization in general propelled all developing countries into the oil age.

•John D. Rockefeller personified the American Dream par excellence, rising from a dishwasher to a multibillionaire. Even in 2019 his surname remains a synonym for immeasurable wealth.

•Though Standard Oil was broken up, successor companies like Exxon-Mobil and Chevron are still operating today.

6 Wheat: The Great Chicago Fire 1872

The Great Chicago Fire of October 1871 leads to massive destruction in the city and leaves more than 100,000 residents homeless. The storage capacities for wheat are also significantly reduced. Trader John Lyon sees this as an opportunity to earn a fortune.

“Being a firefighter is not something you do; it’s something you are.” —the TV show Chicago Fire

The sun burned hot in the American Midwest during the summer of 1871. In and around Chicago, only 3 centimeters of rain fell between July and October. Water resources were nearing depletion, and small fires sprang up regularly. On October 8, a fire broke out in a barn, initiating a disaster that became known as the “Great Chicago Fire.”

Winds from the southwest fanned the flames and set neighboring houses on fire. Traveling quickly, the fire spread toward the city center and crossed the Chicago River. It took two days to get the conflagration under control, and by then an area of more than 8 square kilometers and 17,000 buildings had been destroyed. Every third inhabitant of the city lost his home. The damage has been estimated at more than 200 million USD. In addition to large parts of the city, the fire destroyed 6 out of the 17 warehouses approved by the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). The city’s total storage capacity decreased from about 8 to 5.5 million bushels. John Lyon, a large-scale wheat trader, saw the opportunity to make a profit. He joined with another trader, Hugh Maher, and CBOT broker P. J. Diamond, to manipulate the wheat market.

What’s What with Wheat

Different types of wheat are traded on futures exchanges. In the United States, wheat is traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and the Kansas City Board of Trade (KCBT), with the volume of Chicago Soft Red Winter Wheat (soft wheat) outweighing Kansas Hard Red Winter Wheat (hard wheat). Chicago wheat is mainly grown in an area that extends from Central Texas to the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean. Kansas wheat grows primarily in Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and parts of Texas.

At CBOT, wheat is traded in US cents per bushel and designated with the abbreviation W plus a letter and number that stands for the current contract month (e.g., W Z9 for wheat delivered in December 2019). A contract refers to 5,000 bushels of wheat, with one bushel corresponding to 27.2 kilograms. Therefore, one contract refers to around 136 metric tons of wheat.

In the spring of 1872, the group began to buy wheat in the spot and futures market. Wheat prices rose continuously through early July, and contracts specifying delivery in August traded between 1.16 and 1.18 USD per bushel. At the beginning of July an average of just 14,000 bushels of wheat a day reached the city; by the end of the month, prices had climbed to 1.35 USD. In response, however, wheat deliveries to Chicago increased.

By the beginning of August, 27,000 bushels a day were coming in. But luck was still with Lyon. Another warehouse burned to the ground, and the city’s already stretched storage capacity was reduced by another 300,000 bushels. Rumors about a below-average harvest due to bad weather pushed up prices even more. On August 10 these two factors combined to push wheat contracts for August up to 1.50 USD. On August 15 prices climbed to above 1.60 USD. But then the wheel of fortune started to turn.

As more and more wheat reached the city of Chicago, Lyon was forced to give up.

The high prices incentivized farmers to speed up their harvest: Crops were picked into the night. In the second week of August, about 75,000 bushels of wheat reached Chicago each day; a week later that figure had risen to 172,000 bushels. For the rest of the month, daily deliveries increased to nearly 200,000 bushels.

Wheat that had already been shipped from Chicago to Buffalo returned to the Windy City, because of the high local prices. Newly opened warehouses also added to the storage capacity in the city, bringing it to more than 10 million bushels—two million bushels more than before the Great Fire!

To secure their profits and stabilize prices, Lyon and his partners had to buy all the wheat coming into Chicago. But they were already leveraged by local banks, and the additional funds they needed soon exceeded the group’s financial options.

On Monday, August 19, Lyon had to admit defeat. He could no longer afford to buy wheat in the spot market. The price of wheat with delivery in August fell by 25 US cents. The following day prices dropped another 17 US cents. The crash ruined John Lyon, who was unable to meet his margin calls. His attempt at market manipulation ended in financial disaster and bankruptcy.

Key Takeaways

•The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 led to massive destruction and left more than 100,000 people homeless.

•With the number of grain warehouses drastically reduced, a group of speculators around John Lyon saw a big opportunity in the wheat market. Together they tried to corner the wheat market, but rises in price also resulted in increased shipments of wheat to the city. After initially increasing to 1.60 USD, the price of wheat crashed.

•Lyon and his friends were unable to meet their margin calls. Their attempt at cornering the market ended in bankruptcy and financial disaster.

7 Crude Oil: Ari Onassis’s Midas Touch 1956

Aristotle Onassis, an icon of high society, seems to have the Midas touch. Apparently emerging out of nowhere, he builds the world’s largest cargo and tanker fleet and earns a fortune with the construction of supertankers and the transport of crude oil. Onassis closes exclusive contracts with the royal Saudi family, and he is one of the winners in the Suez Canal conflict.

“The secret of business is to know something that nobody else knows.” —Aristotle Onassis

At the beginning of December 2005 the youngest billionaire in the world, Athina Roussel, age 20, celebrated her wedding to 32-year-old Brazilian equestrian Álvaro Alfonso de Miranda Neto. A thousand bottles of Veuve Clicquot were ordered for the 1,000 guests at the São Paulo nuptials. Athina was the only heiress to the Onassis fortune, the last of her clan. Her grandfather, Aristotle “Ari” Socrates Onassis, would have been almost 100 years old.

A central figure in the high society of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, Aristotle Onassis earned his fortune by constructing supertankers and transporting crude oil. Like Rockefeller, Onassis became synonymous with wealth and fortune. But his rise to fame was not a straightforward one.

The Onassis family initially became wealthy through the tobacco trade. Based in the city of Smyrna, Ari’s father had a fleet of ten ships. Ari himself enjoyed a good education. At 16 he already spoke four languages—Greek, Turkish, English, and Spanish. In 1922, however, when the Turks retook Smyrna (Izmir), which had been under Greek rule since World War I, the family had to flee. They were forced to leave everything behind. Virtually penniless, Onassis migrated to Argentina and earned money by importing tobacco. He also kept himself afloat with occasional jobs.

In the 1930s the world economic crisis offered Onassis an attractive business opportunity in the form of large-scale transport of crude oil.

The economic crisis of the 1930s offered Onassis the opportunity to get into the crude oil transport business on a large scale. There were rumors that the Canadian National Steamship Company was in serious financial difficulties and that several of its freighters were for sale. Onassis took all the money he’d accumulated and purchased six rundown ships for 120,000 USD, one-tenth of their value at the time.

With that bold move, Onassis laid the foundation of his empire. The purchase quickly paid off during the economic recovery that followed. At the beginning of World War II, Onassis’s fleet had grown to 46 freighters and tankers, and he leased them to the Allied forces on profitable terms.

Ari and the Women

Aristotle Onassis married into another family of successful Greek shipowners when he wed Athina “Tina” Livanos. They divorced in the 1950s, however, after he began a long relationship with celebrated opera diva Maria Callas, who separated from her husband for Onassis. In 1968 Onassis married Jacqueline Kennedy, widow of President John F. Kennedy. At the time, Onassis was 62 years old; Jackie was 23 years younger. Because of her spending on travel and shopping, Onassis nicknamed her “supertanker,” since he said she cost him just as much as a ship.

During the war, Onassis’s ships changed their flags to neutral Panama and remained undisturbed by naval battles. As more and more freight ships were lost to the conflict, his own fleet’s rates rose higher, creating a gold mine for Onassis. After the war, he expanded the number of his ships into the largest private commercial fleet in the world, and in 1950, he commissioned the biggest tanker in the world, 236 meters long, to be completed at the German Howaldt shipyard.

But it was not until spring 1954 that the 48-year-old Onassis made a definite breakthrough. Through shady contacts and friendships, he struck a lucrative agreement with the royal family of Saudi Arabia. Onassis not only received the exclusive right to transport crude oil for King Saud, but he also was to produce a new supertanker for the country almost every month and would participate in the sale of crude oil. Together Onassis and Saudi Arabia set up the Saudi Arabian Tanker Company, with a goal of having 25 to 30 ships that could transport about 10 percent of the country’s crude oil.

By royal decree the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) would have had to use Saudi Arabian ships for the tonnage previously shipped in charter ships. Aramco—a joint venture among Standard Oil (New Jersey), Standard Oil of California, Socony Vacuum, and Texas Co.—had had a concession agreement with King Ibn Saud since 1933 and was responsible for nearly 10 percent of the world’s oil production. About half of the oil produced in Saudi Arabia went by pipeline to Lebanon; the other half was transported by tankers. Of the tanker market, 40 percent of crude was shipped in Aramco’s own tankers; for the remaining 60 percent, the company used charters.

The Suez Canal conflict resulted in enormously profitable opportunities for Onassis.

By breaking into this system, Onassis made some powerful enemies. The United States tried to block the agreement to safeguard its own influence, and Europe—which in the 1950s derived 90 percent of its oil supply from the Middle East, whose largest producer was Saudi Arabia—was also unenthusiastic. The deal with Saudi Arabia ultimately fell through, and without the new freight orders, Onassis’s ships sat idle in shipyards around the world. The Greek magnate’s empire began to crumble. But he was rescued by the Suez crisis in 1956.

With the growing economic importance of crude oil, European nations increasingly were dependent on the use of the Suez Canal to bring fuel from the producing countries. But the nationalist policies of the new Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, were intensifying conflicts with Israel as well as with France and Great Britain, which controlled the canal. Egypt blocked the Gulf of Aqaba and Suez Canal to Israeli shipping; then on July 26, 1956, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal.

Britain’s prime minister, Anthony Eden, responded together with Israel and France with Operation Musketeer. On October 29, Israel invaded the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula and quickly pushed toward the canal. Two days later Britain and France began bombing Egyptian airports. Although the Egyptian army was quickly beaten and the war was over by December 22, 1956, sunken ships continued to block the Suez passage until April 1957.

The crisis brought salvation to Aristotle Onassis. No other shipowner had the transport capacity to move the oil. With more than 100 idle tankers and virtually no competition, he was able to double his rates, once again earning a fortune. The Six-Day War in 1967 offered a similar opportunity, and later, during the oil crisis in 1973, Onassis’s Olympic Maritime Company posted a profit of more than 100 million USD.

Aristotle Onassis earned his fortune through the transport of crude oil. He became a society icon through his extravagant lifestyle and his marriage to Jackie Kennedy.

By then, Onassis’s total private wealth was estimated at more than 1 billion USD. Throughout his career he had diversified into other businesses: He bought banks in Geneva, founded Olympic Airways, built the Olympic Tower on Fifth Avenue in New York, and acquired the Greek island of Skorpios. Onassis became enamored of Monaco, which had been a dull, sleepy little place until he transformed it. In Monte Carlo, Onassis bought beautiful hotels and dozens of houses and villas, built public facilities and beach clubs, and renovated the port and the casino. He held legendary gatherings on his yacht, inviting guests who included President John F. Kennedy and his wife, Winston Churchill, Ernest Hemingway, and other members of high society from business, politics, and Hollywood. Onassis even brought together Prince Rainier of Monaco and American actress Grace Kelly, helping establish Monaco as a paradise for the rich and beautiful in Europe.

Key Takeaways

•Aristotle “Ari” Socrates Onassis earned a fortune by transporting crude oil in his huge tanker fleet and through his excellent relationships with the Saudi family.

•He profited massively from the Suez crisis in 1956 and the oil crises of the 1970s.

•Onassis was an icon of the international jet set, thanks to his relationship with opera star Maria Callas, and his second marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy, the widow of John F. Kennedy.

•With his private wealth of more than 1 billion USD, Onassis supported Prince Rainer of Monaco and established the principality as the place to be for the rich and beautiful.

8 Soybeans: Hide and Seek in New Jersey 1963

Soybean oil fuels the US credit crisis of 1963. The attempt to corner the market for soybeans ends in chaos, drives many firms into bankruptcy, and causes a loss of 150 million USD (1.2 billion USD in today’s prices). Among the victims are American Express, Bank of America, and Chase Manhattan.

“You have caused terrific loss to many of your fellow Americans!” US federal judge Reynier Wortendyke

At first glance, it seemed like a plot for a Hollywood movie: Workers deceived warehouse inspectors using oil tanks filled with water to hide one of the largest credit frauds in US history. It was all part of an attempt to corner the soybean market, a fragile house of cards whose collapse caused a loss of more than 150 million USD (the equivalent of about 1.2 billion USD today) and whose effects rippled throughout corporate America.

At the center of the debacle were Allied Crude Vegetable Oil, a New Jersey company, and its owner Anthony (“Tino”) De Angelis. In the end the unraveling of the scheme was analogous to the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008: On a November evening in 1963, a group of employees of the Wall Street brokerage firm Ira Haupt & Co., including managing partner Morton Kamerman, sat in a conference room and spoke on the phone with Anthony De Angelis. As the conversation heated up, De Angelis accused Kamerman of ruining his company. Kamerman was not responsible for his firm’s commodity trading, but he was aware that De Angelis was one of his biggest customers. The Haupt & Co. partners were desperately looking for someone willing to buy soybean oil in large quantities, but they had no success. The next morning Kamerman understood a lot more about his company’s commodity business. However, the knowledge went hand in hand with the fact that Haupt & Co. was bankrupt due to the insolvency of Allied Crude.

Some Background About Soybeans

Soybeans, which are predominantly crushed for soybean oil and soybean meal, are produced and exported mainly by the United States “Corn Belt” (Illinois and Iowa), Brazil, and Argentina. Together these countries account for about 80 percent of the world’s soybean harvest of around 215 million metric tons. In most of the world’s production, the oil is extracted first, and the residual mass is used primarily as a feedstock. Soybeans, soybean meal, and soybean oil are traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) with the symbol S, SM, and BO and the respective contract month (for example, S F0 = Soybean January 2020).

Anthony De Angelis had founded Allied Crude Vegetable Oil in 1955 to buy subsidized soybeans from the government, process them for soybean oil, and sell the product abroad. Born in 1915, he was the son of Italian immigrants and grew up in the Bronx in New York. As a commodity trader, he dealt in cotton and soybeans, and between 1958 and 1962, he built a refinery in Bayonne, New Jersey, and leased 139 oil tanks, many as high as a five-story building. American Express Warehousing, a subsidiary of American Express, was paid by Allied Crude for storage, inspection, and certification of the oil volume. In 1962 De Angelis was responsible for about three-quarters of the total soybean and cottonseed oils in the United States. But in order to finance the rapid growth of the company in a highly competitive industry, he increased leverage by taking more and more credit, which was largely collateralized by the oil he produced.

And that is where the fraud began: Allied Crude Vegetable Oil never had as much oil as was necessary to secure its loans. A close investigation by American Express Warehousing would have revealed that De Angelis needed to store more oil than was available in the entire United States, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s monthly data. At its peak, De Angelis’s credit volume represented more than three times the amount of oil that could be stored in the tanks in Bayonne. But De Angelis was American Express’s largest customer. And his employees deceived the inspectors who were sent to check the collateral by pumping oil from tank to tank or filling the tanks mainly with water and only a small amount of oil. In this way the company continued to receive new credit lines.

Instead of expanding operations, however, the company used the credit lines for speculation in soybean futures at Chicago’s commodity exchange. De Angelis placed huge bets on rising prices for soybeans; he had to deposit only about 5 percent of the future purchase sum as a margin. Nevertheless, in his attempt to corner the entire market through further positions, De Angelis needed an even higher credit line.

He was already trading in futures contracts with Wall Street brokers Ira Haupt and J. R. Williston & Beane, and they agreed to further credit against stockpiles of the nonexistent oil. Both institutions were financed on the basis of their warrants by commercial banks Chase Manhattan and Continental Illinois.